Béu : Chapter 3: Difference between revisions

| Line 398: | Line 398: | ||

The word '''wepua''' is derived from '''pè''' meaning "to need". '''pòi''' means necessities.'''wepua''' can be thought of as meaning something like "being necessary" or "of necessity". | The word '''wepua''' is derived from '''pè''' meaning "to need". '''pòi''' means necessities.'''wepua''' can be thought of as meaning something like "being necessary" or "of necessity". | ||

=== 4 suffixes -u, -va, -inda, -wan === | |||

These all form adjectives. The first 2 might have some connection with the '''seŋgeba'''. | |||

i.e. '''solbe''' = to drink | |||

'''moze''' = water | |||

'''moze solbu''' = the water which must be drunk | |||

'''moze solbeva''' = drinkable water | |||

There is also another suffix, but this one can be said to be unrelated to "like" | |||

'''moze solbinda''' = water worth drinking | |||

'''bawa solbewan''' = men inclined to drink | |||

The last one also makes adjectives from other adjectives. i.e. | |||

'''hìa''' = red | |||

'''hiawan''' = reddish | |||

And it can make nouns from nouns | |||

'''alha''' = flower | |||

'''hawan''' = a bee | |||

== ..... Index== | == ..... Index== | ||

{{Béu Index}} | {{Béu Index}} | ||

Revision as of 19:27, 19 February 2013

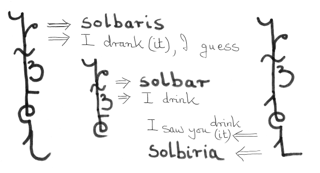

..... The R-form of the verb

So far we haven't said much about the verb as such, although we have come across the infinitive (gomia).

We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter.

Above it is shown appearing in some active verbs. Just remember to put an extra little florish on the "r" when it occurs word finally, just to distinguish it from word final "j".

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb.

So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause (semo) = that which has one "r" ... ??? )

O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the gomia*.

1) the final vowel is deleted from the gomia.

*Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech")

... Slot 1

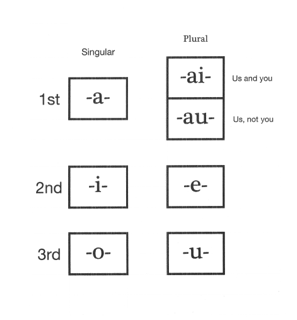

2) one of the 7 vowels below is added.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons.

Note that the ai form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

... Slot 2

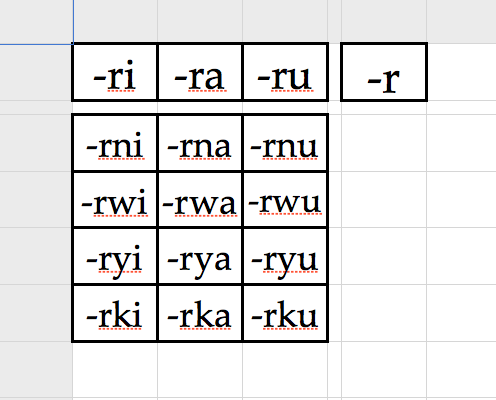

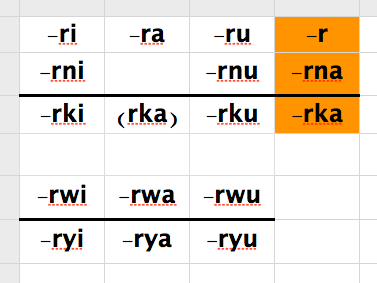

3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.*

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

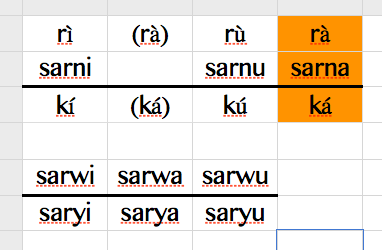

The table above has the gwoma arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the gwoma arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative -rka followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example doikara = I am walking ... (doika = to walk)

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in béu the pattern is broken a bit, in that -rna has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also béu and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use doikarna in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact doikar is used. doikarna would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift)

doikarna = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row expresses the perfect tense.

While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

Easy to translate into English ... doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next row expresses the "not yet" tense.

Easy to translate into English ... doikoryi = He/she had not yet walked ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked

Notice that the English translation, doikoryu is just the negative of doikorwu. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way.

Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative).

Just as -rna does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, -rka gives a tenseless negative.

Easy to translate into English ... doikorki = He/she didn't walk ... doikorka = He/she doesn't walk ... doikorku = He/she will not walk

You may have noticed that the béu letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs (bù). This is pure coincidence.

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, pomo, fene, and liʒi.

*But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. béu has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the r form of the verb plus the béu equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough.

... Slot 3

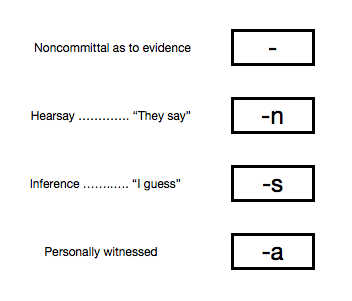

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based.

a) doikori = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying.

b) doikorin = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

c) doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow.

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The fourth tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

d) doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

This last teŋko can only be used with one of the gwomai . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form i.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

..... Copula's

The word copula comes from the Latin word "copulare" meaning "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu(as in other languages) they differ from normal verbs in that they are quite irregular.

Also in béu a copula clause taiviza requires a specific word order and the s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to any noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

... sàu

sàu is the béu main copula and is the copula of state. It is the equivalent of "to be" in English, which has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

The table below echoes the second table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In three rows (the second and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In rows 1 and 3 the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when these form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Actually rà is usually dropped completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gì ká moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pà rà moltai = I am a doctor

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when the subject or the copula complement are long trains of words. For example ????????

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

... láu

láu is the béu is the copula of change of state. It is the equivalent of "become" in English.

Again the table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In four rows (the second, third and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In the first row the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when this form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

As you can see this copula is more regular than the main copula.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

láu hauʔe = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

... The existential strategy

Some languages have a verb to indicate that something exists. béu has not. In fact to show that something exists béu uses exactly the same mechanism as English ...

há = place

dí = this

dè = that

While you sometimes come across the há dí the word hái is the usual way to express "here".

In a similar manner you sometimes come across the há dè the word ade* is the usual way to express "there".

*This word is an exception to the rule that inside a word and between vowels, d can be either pronounced as "d" or "ð". In ade the d is always pronounced "ð".

There is a house = A house exists = ade (rà) nambo

This is patterned on the more general locative construction.

In the apple tree is a beehive ????

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" is "there exists a coat mine" = ade kaunu paʔe

Internal possessives are not allowed in the nouns introduced with ade. And although we have a genitive pilana it is always the locative pilana, -ʔe found in this construction, Why ???

ade pona paye = "I feel cold" ... maybe against expectations ... no reason to think that other people would be cold.

ʃi pona = "It is cold" ... everybody should feel cold

..... The verb complex or verb phrase

Also often called the predicate. Called the jaudauza in béu

The predicate is made up of ...

1) one of two particles that show likelihood which are optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called mazebai. The mazebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

2) one of five particles that show modality. These are also optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called seŋgebai. The seŋgebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

3) a gomua (a full verb)

... mazebai

These appear first in the predicate.

These particles show the probability of the verb occurring.

1) màs solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

You could say that the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty

... seŋgebai

These appear next in the predicate.

These particles correspond to what is called the "modal" words in English. The five seŋgeba are ...

1) sú which codes for strong obligation or duty. It is equivalent to "should" in English. In English certain instances of the word "must" also carries this meaning.

2) seŋga which codes for weak obligation. It is equivalent to "ought to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "ought to" is dying out, and "should" is coding weak obligation also)

3) alfa which codes for ability. It is equivalent to "can" in English. As in English it means that subject has the strength or the skill to perform the action. Also as in English it codes for possibilities/situations which are not dependent on the subject. For example ... udua alfa solbur => "the camels can drink" in the context of "the caravan finally reached Farafra Oasis"

4) hempi which codes for permission. It is equivalent to "may" or "to be allowed to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "may" is dying out, and "can" is coding for permission also)

5) hentai means knowledge. It is equivalent to "know how to" in English. (Note ... in English certain instances of the word "can" also carries this meaning)

The form that these seŋgeba and the main verb take appears strange. Where as, logically, you would expect the suffixes for person, number, tense, aspect and evidential to be attached to the seŋgeba and the main verb maybe in its infinitive form, the seŋgeba do not change their form and the suffixes appear on the main verb as normal. This is one oddity that marks the seŋgeba off as a separate word class.*

Some examples ...

1)

a) sú -er => you should visit your brother

b) sú -eri => you should have visited your brother

c) sú hamperka animals => you should not feed the animals

d) sú hamperki animals => you shouldn't have fed the animals

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza súa

2)

a) seŋga humper little => you ought to eat a little

b) seŋga humperi little => you ought to have eaten a little

c) seŋga solberka brandy => you ought to not drink brandy

d) seŋga solberki brandy => you ought to have not drunk that brandy

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza seŋgua

3)

a) fà -or => he can swim across the river

b) fà-ori => he could swim across the river

c) fà solborka => he can stop drinking

d) fà solborki => he could stop drinking

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza fùa

4)

a) hempi bor festa => "she may go to the party" or "she can go to the party" or "she is allowed to go to the party"

b) hempi bori festa => she was allowed to go to the party

c) hempi borka school => he is allowed to stop attending school

d) hempi bori school => he was allowed to stop attending school

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hempua

5)

a) hentai bamor car => "she can drive a car" or "she knows how to drive a car"

b) hentai bamori car => she knew how to drive a car

c) hentai boikorka car => He has the ability not to crash the car

d) hentai boikorki car => He had the ability not to crash the car

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hentua

*Two other oddities also marks off the seŋgeba as a separate word class. These are ...

1) When you want to question a jaudauza containing a seŋgeba you change the position of the main verb and the seŋgeba. For example ...

bor hempi festa => "may she go to the party" ... shades of English here.

2) All 5 seŋgeba can be negativized by deleting the final vowel and adding aiya. For example ...

faiya -or ??? => he can't swim across the river

Note ... sometimes the negative marker on the seŋgeba can occur along with the normal negative marker on the main verb to give an emphatic positive. Sometimes it produces a quirky effect. For example ...

jenes faiya humpor cokolate => Jane can't eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability to eat chocolates) ... for example she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jenes fa humporka cokolate => Jane can not eat chocolates (Jane have the ability not to eat chocolates)... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jenes faiya humporka cokolate => Jane can not not eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability, not to eat chocolates) ... meaning she can't resist them.

There are 5 nouns that correspond to the 5 seŋgeba

anzu = duty

seŋgo = obligation

alfa = ability

hempo = permission or leave

hento = knowledge

Note on English usuage (in fact all the Germanic languages) ... the way English handles negating modal words is a confusing. Consider "She can not talk". Since the modal is negated by putting "not" after it and the main verb is negated by putting "not" in front of it, this could either mean ...

a) She doesn't have the ability to talk

or

b) She has the ability to not talk

Note only when the meaning is a) can the proposition be contracted to "she can't talk". In fact, when the meaning is b), usually extra emphasis would be put on the "not". a) is the usual interpretation of "She can not talk" and if you wanted to express b) you would rephrase it to "She can keep silent". This rephrasing is quite often necessary in English when you have a modal and a negative main verb to express.

... wepua

We have already mentioned the two mazeba at the beginning of this section.

Actually there is another particle that occurs in the same slot as the mazeba and it also codes for likelihood. This is wepua and it constitutes a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles) all by itself.

1) más solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

3) wepua solbori = he must have drank

You could say that while the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty, the third shows 100% certainty.

3) Indicates that some "evidence" or "background information" exists to allow the speaker to assert what he is saying. It also carries the meaning "there is no other conclusion given the evidence".This obviously has some functional similarities to the -s evidential. However the -s evidential carries less than 100 % certainty ...

solboris = I guess/suppose he drunk

wepua never appears in front of the first two seŋgebai. This is the difference between wepua and the mazebai.

The word wepua is derived from pè meaning "to need". pòi means necessities.wepua can be thought of as meaning something like "being necessary" or "of necessity".

4 suffixes -u, -va, -inda, -wan

These all form adjectives. The first 2 might have some connection with the seŋgeba.

i.e. solbe = to drink

moze = water

moze solbu = the water which must be drunk

moze solbeva = drinkable water

There is also another suffix, but this one can be said to be unrelated to "like"

moze solbinda = water worth drinking

bawa solbewan = men inclined to drink

The last one also makes adjectives from other adjectives. i.e.

hìa = red

hiawan = reddish

And it can make nouns from nouns

alha = flower

hawan = a bee

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences