Béu : Chapter 4: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

Can this be used for a causative construction ?? | Can this be used for a causative construction ?? | ||

== ..... Copula's== | == ..... Copula's== | ||

Revision as of 16:28, 6 February 2013

..... Building up a noun phrase ... "cwidauza"

Now we talk about the béu noun phrase (cwidauza). This can be described as ;-

Quantifier1 Head2 (Adjective3 x n) Genitive4 Determiner5 Relative-clause6

1) The Quantifier is either a number or a word such as "all", "many", "a few" etc.

2) The head is usually a noun but can also be an adjective. When you come across an adjective as head of a noun phrase, its meaning is "the person/thing that is "adjective" ".

3) An adjective ... not much to say about this one, you can have as many as you like, the same as English.

4) A Genitive is made from a noun (and I guess an adjective as defined in 2) ) with an n suffix. It says that the head has some quality or relationship to the genitive.

5) Either dí "this", or dè "that".

6) This is a clause, beginning with tà that qualifies the head of the noun phrase.

An interesting point is that in the absence of a "head" any of the other 5 elements can constitute a NP by itself.

..... laite

laite is a relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativizer is tá. The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the relativizer tá. For example ;-

glà tá bwás timpori rà hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

bwá tás timpori glà rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

The same thing happens with all the pilana. For example ;-

the basket tapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall tala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman taye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town tavi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad talya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat talfe you have just jumped is unsound

bwà tás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo taʔe she lives is the biggest in town.

bwà taho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife tatu he severed the branch is a 100 years old

the man tan dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police*

The old woman taji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy taco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

..... kolape

This is a complement clause construction. There are 3 types of kolape.

kolape jù

In béu the word order is usually free. This is not true in a kalope jù

jonoS rì kéu = John was bad

(pà solbe moze pona sacowe)S rì kéu = my drinking the cold water quickly was bad

Notice that pà solbe moze pona sacowe behaves as one element. It has the same function as "John" in the previous example.

The word order inside kolape jù is fixed. It must be S V or A V O for a transitive clause (any other peripheral arguments are stuck on at the end).

Also notice that the ergative marker -s which is usually attached to the A argument is dropped. Actually for pronouns it is not just the dropping of the -s, but a change of tone also, so this form is identical to the O form of the pronoun.

The kolape above, if expressed as a main clause would be.

(pás) solbari saco* moze pona = I drank the cold water quickly

Other examples ;-

wàr solbe (I want to drink) is another example. (wò = to want)

klori jono timpa jene (he saw John hitting Jane) ... (klói = to see)

kolape jù? can be considered as a noun phrase and the fixed ordering of elements can be seen as a reflextion of the strict order of elements in a normal noun phrase

Subject1 Head2 Object3(Peripheral arguments4 x n)

1) The "A" argument or the "S" argument.

2) The verb.

3) The "O" argument, which would of course be non-existent in an intransitive clause.

4) Adverbs and everything else.

A gomia such as solbe can be regarded as a proper noun** and can be the head of a cwidauza (see a previous section)

or it can be the head of a kalope jù. But these two constructions are always distinct. For example you couldn't append a determiner to a kalope jù ... (or could you ??)

* in a main clause the adverb can appear anywhere if suffixed with -we. But in kalope jù the adverb must come after the Subject, Verb and Object.

** A gomia never forms a plural or takes personal infixes in the way a normal noun does. Also it only takes a very reduced subset of pilana, so a gomia can be regarded as an entity half way between nounhood and verb hood. For that reason I consider gomia as a part of speech, standing alongside "noun" and "verb".

kolape tà

In this form the full verb* is used, not the gomia. Also we have a special complementiser particle tà which comes at the head of the complement clause.

wàr tà jonos timporu jene = I want John to hit Jane

klori tà jonos timpori jene (he saw that John hit Jane) ... (klói = to see)

*Well not quite the full form. Evidentials are never expressed.

kolape tavoi

This is equivalent to English word "whether".

sa RAF kalme Luftwaffe kyori Hitler olga tena => The RAF's destruction of the Luftwaffe, made Hitler think again. ... here a gomiaza acts as the A-argument.

*in the combinations where sacowe immediately followed solbe it is merely saco

Things to think about

what about "who" or "what" introducing a relative clause ?

what is a gomiaza

Can this be used for a causative construction ??

..... Copula's

The word copula comes from the Latin word "copulare" meaning "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu(as in other languages) they differ from normal verbs in that they are quite irregular.

Also in béu a copula clause taiviza requires a specific word order and the s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to any noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

sàu

sàu is the béu main copula and is the copula of state. It is the equivalent of "to be" in English, which has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

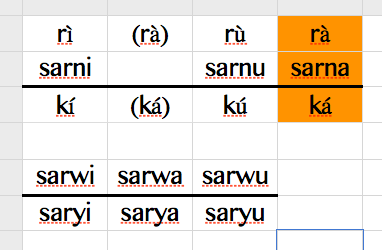

The table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In three rows (the second and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In rows 1 and 3 the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when these form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Actually rà is usually dropped completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gì ká moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pà rà moltai = I am a doctor

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when the subject or the copula complement are long trains of words. For example ????????

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

láu

láu is the béu is the copula of change of state. It is the equivalent of "become" in English.

Again the table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In four rows (the second, third and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In the first row the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when this form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

As you can see this copula is more regular than the main copula.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

láu hauʔe = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

The existential strategy

Some languages have a verb to indicate that something exists. béu has not. In fact to show that something exists béu uses exactly the same mechanism as English ...

há = place

dí = this

dé = that

While you sometimes come across the há dí the word hái is the usual way to express "here".

In a similar manner you sometimes come across the há dè the word ade* is the usual way to express "there".

*This word is an exception to the rule that inside a word and between vowels, d can be either pronounced as "d" or "ð". In ade the d is always pronounced "ð".

There is a house = A house exists = ade (rà) nambo

This is patterned on the more general locative construction.

In the apple tree is a beehive ????

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" is "there exists a coat mine" = ade kaunu paʔe

Internal possessives are not allowed in the nouns introduced with ade. And although we have a genitive pilana it is always the locative pilana, -ʔe found in this construction, Why ???

ade pona paye = "I feel cold" ... maybe against expectations ... no reason to think that other people would be cold.

ʃi pona = "It is cold" ... everybody should feel cold

Verb chains

bawas loʔura nambo laulai halfai => The men go home singing and laughing

bawas loʔura nambo laulai lauloi halfai => The men go home singing songs and laughing

bawas loʔura nambo laulai halfai jono => The men go home singing and laughing about John

This is used when things happen at the same time and the subject of all the verbs is the same. Notice that the ai-forms can come after the r-form verb.

The verb which is considered the most relevant/important comes first.

The three verbs above sort of amalgamate into a single verb.

In the examples above the three constituent verbs of the verb chain happen at the same time but this is not always the case. In the example below the constituent verbs happen one after the other.

Take ball go give John.

Minor Verb "ai"

The small verbs constitute a subset of verbs. They always follow the r-form verbs.

It is very common to have the following verbs in their ai-form.

bià means "to stay"

bài doikari = I was walking

bài doikara = I am walking

bài doikaru = I will be walking

The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in béu anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)".

láu = to become

I painted the house red = paintari nambo lái hìa

bwò = to receive, to get, to undergo

bwaru timpa = I will be hit

bài bwài timparu = I will be being hit ??

kye = to give

kyari òye solbe

(pás) kyari oye timpa glá = I made him hit the woman

gain only one verb and it is transitive. There are two ways that we can make an intransitive clause.

1) pintu lí mapa = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu.

Agent => Anything ... It could be that the agent was the wind ... or even some evil spirits ... use your imagination.

2) pintu bwori mapau = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate ... It strongly implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant.

Let us go back to gèu and consider gèu in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways.

1) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Agent => Anything and the action could be accidental.

2) báu bwori geuldu = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate

3) báu tí geuldori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved.

Agent => The man and the action deliberate

= to come

= to go

= to rise ... sái : to raise ... slái

= to descend ... gàu : to lower ... glàu

= to enter ... poi : to put in ... ploi

= to go out

= to follow

= to cross

= to go through

= to pass

= to return

= to do something in a haphazard manner, to do something in an unsatisfactory manner

= to scatter about

= to hurry

= to do accidentally ??

The above are often stuck on the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution.

See what Dixon has in Dyirbal.

ai-form only with r-form or can also go with n-form, etc. etc.

You can add as many verbs as you want. The added verbs are understood to have the same protagonists, gwomai and evidentiality as the r-form verb.

passorla singai kite flyai = He is passing by singing and flying a kite

WHAT ABOUT SEPERATE OBJECTS ON THE TWO VERBS ?

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ???

The causative construction

(pás) dari jono dono = I made john walk

(pás) dari jono timpa jene = I made John hit Jane ... in this sort of construction, jono, timpa and jene must be contiguous and jono should be to the left of jene.

To give and to receive ... kyé and bwò

kyé means to give and bwò means to receive or get.

1) jonosA kyori jene toiliO or jonosA kyori toili jeneyeO = John gave a book to Jane "or" John gave Jane a book

Linguistic jargon ... In the Western linguistic tradition, Jane is called "the indirect object"(IO). Quite an unfortunate term I think as it is human 99% of the time, hence hardly what you would normally call an object.

Notice that the béu usage is the exact same as English.

2) jeneA bwori toiliO (jonovi) = Jane got a book (from John)

O.K. the above is the usage normal usage of kyé and bwò. They sort of describe the same action but from two different perspectives.

The passive construction

3) jonosA timpori jeneO = John hit Jane

4) jeneS bwori timpa (jonotu) = Jane was hit

4) is the passive equivalent of 3) ... used when the A argument is unknown or unimportant.

If the agent is mentioned, he or she tale the instrumentiv pilana.

Other examples ...

jene bwori du dono = Jane was made to walk

(pás) bwari du solbe moze (jonotu) = I was made to drink the water (by John)

moze bwori solbe (jenetu) = The water was drunk (by Jane)

fompe is an intransitive verb

flompe is a transitive verb

jene fompori = Jane tripped

jonos flompori jene = John tripped Jane

(pás) dari jono jene flompe = I made John trip Jane

Changing transitivity

béu has 2 morphological ways to make all these type of verbs into transitive verbs ( see -at- and -az- causatives).

-AT- and -AZ-

tonzai = to awaken

tonzatai = to wake up somebody (directly) i.e. by shaking them

tonzazai = to wake up somebody (indirectly) i.e. by calling out to them

henda = to put on clothes

hendata = to dress somebody (for example, how you would dress a child)

hendaza = to get somebody to dress (for example, you would get an older child to dress by calling out to them)

The above methods of making a causative only apply to intransitive verbs. To make an transitive clause onto a causative the same method is used as English used. That is the entire transitive clause becomes a complement clause of the verb "to make".

In addition to the causative infixes shown above, there are many verb pairs such as poi = to enter, ploi = to put in, gau = to rise, glau = to raise, sai = to descend, slai = to lower

and in multisyllable words ... laudo = to wash (oneself), lauldo = to wash (something). The above are not really considered causatives. The infixing of the l is by no means productive. In fact you can not call it "infixing". Also in many cases the transitive verb out of the pair is more common than the intransitive one.

Note;- The way you say "allow" or "let" in béu is to use the gambe along with the hái "give".

I let her go => hari liʔa oye

.

..... pilana or the case system

..

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 14 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play in the clause**.

The pilana are abbreviated to a single consonant in the béu writing system. That is, in the béu writing system, the final vowel of all pilana is invisible***.

The pilana are partly an aid to quicker writing. However they also demarcate a set of 14 affixes and make quite a neat system.

You could call these 14 plus the unmarked noun a case system of 15 cases. Well you could if you wanted to (up to you).

Note that -lya and -lfe are represented by a special amalgamated symbols which do not occur elsewhere.

Notice that by a addition of pilana, you might expect to get the forms alye and alfi. As you can see this is not the case. Perhaps the amalgamated form has the final vowel changed under the pull of the initial vowel, a.

* You can tell if pilana is being an adjective or a noun by the environment that you find it in.

** Well actually that is not true of pilana number 12 : "-n" modifies a noun in a noun phrase.

***Maybe a corollary of the béu habit of dropping verbal arguments, when it is at all possible :-)

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana, the whole thing must be contiguous. So it this case the affix must become a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

The letters m, b, k, g and d are free to be used as abbreviations. Perhaps m <= mò, two particles for joining clauses etc. etc.

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

-pi or pì : pilana naja ... (the first pilana)

meu (rà) "basket"pi

While the original meaning was about space, this pilana is very often found referring to time.

I read the book hourpi => I read the book in an hour

I gets dark pi ten minutes => It get dark in ten minutes

She qualified as a doctor pi five years

One can get from Glasgow to London daypi

I'm coming to Sweden pi next month

meu (rà) topla basketn = The cat is on top of the house

meu (rà) interior basketn = the cat is in the basket

-la or lá : pilana nauva ... (the second pilana)

mat (rà) floorla => the mat is on the floor ... notice "the mat"

ʔá mat floorla => there is a mat on the floor ... notice "a mat"

meu (rà) top.la nambo.n => The cat is on top of the house

ʔaya "money" nà pà => I don't have any money ... notice that "money" is indefinite ...

Do I need the three copula's ? ... how quickly would they collapse to two or one ?

-ye or yè : pilana naiba ... (the third pilana)

xxx yyy oye = give the book to her

xxx yyy paye = tell me about it

This is the pilana used for marking the receiver of a gift, or the receiver of some knowledge.

However the basic usage of the word is directional.

*namboye => nambye = "to the house"

.

ye "distance" nà nambo = "as far as the house"

ye "limit" nà nambo = "up to the house" ... this usage is not for approaching humans however ... for that you must use "face".i.e. ye "face" nà báu = right up to the man

.

"direction" nà nambo = towards the house i.e. you don't know if this is his destination but he is going in that direction

yèu = to arrive ... yài a SVC meaning "to start" ... fái a SVC meaning "to stop" ???

-vi or fí : pilana nuga ... (the fourth pilana)

nambovi = "from the house"

fí "direction" nà nambo = "away from the house" i.e.you don't know if this is his origin but he is coming from the direction that the house is in.

fí "limit/border" nà nambo = all the way from the house

fí "top" nà nambo = from the top of the house ... and so on for "bottom", "front", etc. etc.

he changed frog.vi ye prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

fía = to leave, to depart ... fái a SVC meaning "to finish" .... then bai cound mean continue and -ana would be the present tense ???

-lya or alya : pilana nida ... (the fifth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Allative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here. Can be said to translate to English as "onto".

xxx yyy zzz = put the cushions on the sofa

-lfe or alfe : pilana nela ... (the sixth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Ablative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here.

-s or sá : pilana noica ... (the seventh pilana)

that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting that job

swe ta ........

-ʔe or ʔé : pilana neza ... (the eighth pilana)

ò (rà) namboʔe = He is at home

Notice that there are to ways to say "He is at home" ... or at anywhere (could there be some grammatic distinction between them ??)

In a similar manner when a destination comes immediately after the verb loʔa "to go" the pilana -ye is always dropped.

In a similar manner when a origin comes immediately after the verb kome "to come" the pilana -vi is always dropped.

(Hold on I have to think about the above two ... not symmetrical, what about Thai)

The plovaza

The plovaza (adjective phrase) is a clause that sets the scene for the main action.

1) "waiting on tables six nights a week", Kirsty had come to know all the regular customers // "their mains flowing", they ran across the field and down to the river.

2) "his leg broken", he slowly crawled up the sand dune and ...

3) "having to pack all the stereos before lunch", he did not stop for a tea-break.

The plovaza

The plovaza (adjective phrase) is a clause that sets the scene for the main action.

1) "waiting on tables six nights a week", Kirsty had come to know all the regular customers // "their mains flowing", they ran across the field and down to the river.

2) "his leg broken", he slowly crawled up the sand dune and ...

In English grammar this is called a nominative absolute construction. It is a free-standing (absolute) part of a sentence that describes or modifies the main subject and verb. It is usually at the beginning or end of the sentence, although it can also appear in the middle. Its parallel is the ablative absolute in Latin, or the genitive absolute in Greek.

..... The Calendar

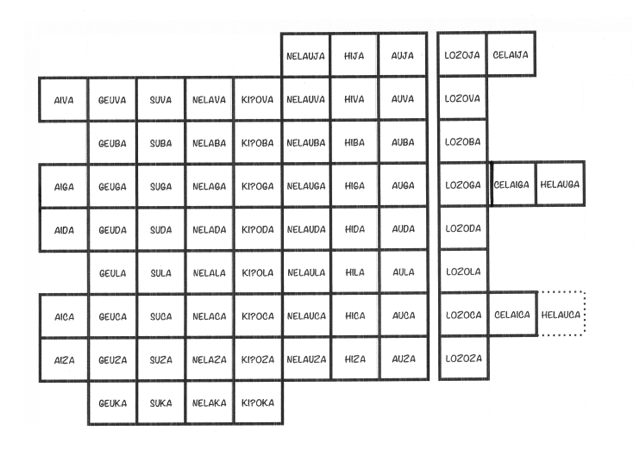

The béu calendar is interesting. Definitely interesting. A 73 day period is called a dói. 5 x 73 => 365.

The phases of the moon are totally ignored in the béu system of keeping count of the time.

The first day of the dói is nelauja followed by hija, then auja lozoja celaija and then aiva etc. etc. all the way upto kiʔoka.

The days to the right are workdays (saipito) while the days to the left are days off work (saifuje). Each month has a special festival (hinta) associated with it. These festivals are held in the three day period comprising lozoga, celaiga, helauga. The five "months" are named after the 5 planets that are visible to the naked eye. The 5 big festivals that occur every year are also named after these planets.

| mercury | ʔoli | Month 1 | doiʔoli | Xmas... on 21,22,23 Dec | hinʔoli |

| venus | pwè | Month 2 | doipwe | festival on 4,5,6 Mar | himpwe |

| mars | gú | Month 3 | doigu | festival on 16,17,18 May | hiŋgu |

| jupiter | gamazu | Month 4 | doigamazu | festival on 28,29,30 July | hiŋgamazu |

| saturn | yika | Month 5 | doiyika | festival on 9,10,11 Oct | hinyika |

hinʔoli ... This is the most important festival of the year. It celebrates the starting of a fresh year. It celebrates the stop of the sun getting weaker. It is centred on the family and friends that you are living amongst. Even though eating and drinking are involved in all the five festivals, this festival has the most looked-forward-to feasts.

himpwe ... People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various music and poetry competitions. Sky lanterns are usually released on the last day of this festival. On the first two days of the festival, what is called the "fire walk" is performed. This is to promote social solidarity. Each locality comprising up to 400 people build a fire in some open ground. These people are divided into 2 sections. One section to walk and one section to receive walkers. The walkers are further divided into groups. Each group is assigned another fire to visit and they set of in single file. Each of them carries a torch (a brand) ignited from the home fire. Upon arriving at the fire that they have been assigned (involving a walk of, maybe, 5 or 6 miles) they throw their brand into the fire as their hosts sing the "fire song". After that the visitors are offered much drinks and snacks by their hosts. There is considerable competition between the various localities to be the most generous host. The routes that people must go have been chosen previously by a central committee, but the destination is only revealed to the walkers just before they set out. On the second day the same thing happens but the two sections, the walkers and the receivers of the walkers, swap over rolls.

hiŋgu ... It is usual to get together with old friends around this time and many parties are held. Friends that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken to meet up with old acquainances. Also there is a big exchange of letters at this time. The most important happenings of the last year are stated in these letters along with hopes and plans for the coming year.

hiŋgamazu ... This festival is all about outdoor competitions and sporting events. It is a little like a cross between the Olympics games and the highland games. People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various team and individual competitions. However care is taken that no regional centre becomes too popular and people are discouraged from competing at centres other than their local one. Also at this festival, a "fire walk" is done, just the same as at the "himpwe" festival.

hinyika ... Family that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken for family visits and ancestors ashboxes are visited if convenient. This is the second most important festival of the year. People often take extra time off work to travel, or to entertain guests. Fireworks are let of for a 2 hour period on the night of helauga. This is one of the few occasions where fireworks are allowed.

By the way, when a year changes, it doesn't change between months, it changes between lozoga and celaiga.

Every 4 years an extra day is added to the year. The doiʔoli gets a helauca.

béu also has a 128 year cycle. This circle is called ombatoze. There is a animal associated with every year of the ombatoze.

These animals are ;-

| wolf | weasel/ermine/stoat/mink | bullfinch | badger |

| whale | opossum | albatross | beautiful armadillo |

| giant anteater | lynx | eagle | cricket/grasshopper/locust |

| reindeer | springbok | dove | gnu/wildebeest |

| spider | Steller's sea cow | seagull | gorilla |

| horse | scorpion | raven/crow | python |

| rhino | yak | Kookaburra | porcupine ? |

| butterfly | triceratops | penguin | koala |

| polar bear | manta-ray | hornbill | raccoon |

| crocodile/alligator | wolverine | pelican | zebra |

| bee | warthog | peacock | capybara |

| bat | bear | crane/stork/heron | hedgehog |

| frog | lama | woodpecker | gemsbok |

| musk ox | chameleon | hawk | cheetah |

| lion | frill-necked lizard | toucan | okapi |

| dolphin | aardvark | ostrich | T-rex |

| kangaroo | hyena | duck | driprotodon(wombat) |

| shark | cobra | kingfisher | gaur |

| dragonfly | mole | moa | chimpanzee |

| turtle/tortoise | N.A. bison | black skimmer | panda |

| jaguar | snail | cormorant/shag | Cape buffalo |

| rabbit | colossal squid | vulture | glyptodon/doedicurus |

| beetle | seal | falcon | pangolin |

| megatherium | woolly mammoth | flamingo | baboon |

| elk/moose | squirrel | blue bird of paradise | lobster |

| tiger | gecko | grouse | seahorse |

| jackal/fox | octopus | swan | lemur |

| elephant | swordfish | parrot | auroch |

| giraffe | ant | puffin | iguana |

| mouse | crab | swift | mongoose/meerkat |

| smilodon | giant beaver | owl | mantis |

| camel | goat | hummingbird | walrus |

Each of these animals above is a toze, which can be translated as "token", "icon" or "totem ". omba means a circle or cycle. So you can see where the name for the 128 year period comes from.

The very last helauca of every ombatoze is dropped.

ombatoze is sometimes translated as "life", "generation" or "century"

xxx means a 4 year period. It also means "calendar".

..... Simple arithmetic

noiga = arithmetic

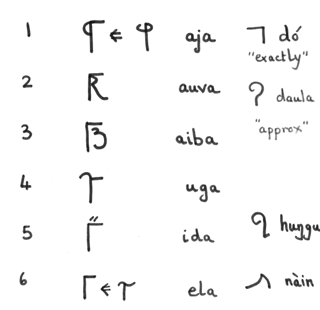

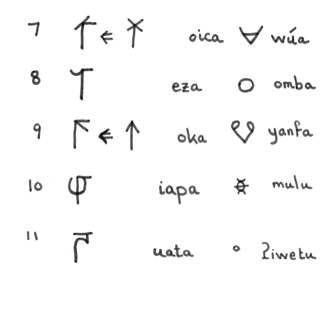

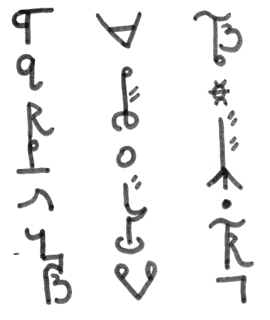

Above right you can see the numbers 1 -> 11 displayed. Notice that the forms of 1, 3, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

In the bottom right you can see 7 interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the béu number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). Their meanings are given in the table below.

| elephant | huŋgu |

| rhino | nàin |

| water buffalo | wúa |

| circle | omba |

| hare | yanfa |

| beetle | mulu |

| bacterium, bug | ʔiwetu |

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

This monster would be pronounced aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dó

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point"/"decimal" when reeling off a number.

When first introduced to this system, many people think that the béu culture must be untenable, however strangely enough the béu culture has lasted many thousands of year, despite the obvious confusion that must arise when they attempt to count elephants.

One further point of note ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say auvaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630" instead of "630 micro".

To make a number negative the "number bar" is placed on the left. See below ;-

Also a number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". See below ;-

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the "addition operation". The numbers are simply written one beneath the other. Similarly with subtraction but one number would be negative this time.

There is a special sign to indicate multiplication (+), and there is an equals sign (-).

Division is the same as multiplication except that one of the numbers is in "fractional form".

There is an alternative multiplication/division notation : instead of using the + sign, the two quantities can instead be written side by side (see the example above).

-6 is pronounced ela liʒi ... liʒi means left or "negative

By the way lugu means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive.

4i is pronounced uga haspia ... and what does haspia mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing.

-4i is pronounced uga haspia liʒi

-1/10 is pronounced diapa liʒi

i/4 is pronounced duga haspia

..... Star time

Year 2000 had 365.242,192,65 days

Every year is shorter than the last by 0.000,000,061,4 days

By adding one day every 4 years we get a 365.25 day year

If we then drop one day every ombatoze we get a 365.242,187,5 day year (actually very close to the actual year length)

Before 2084, the actual year will be bigger than the calendar year – after 2084 the actual year will be smaller than the calendar year

For this reason midnight, 22 Dec 2083 is designated the fulcrum of the whole system. That day will be time zero.

At the moment we are in negative time.

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences