Béu : Chapter 5: Difference between revisions

(→Units) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=='''- | =='''-ho''' or '''hò''' : '''pilana noka''' ... (the ninth pilana)== | ||

"in the company of", often used with the personal pronouns ;- | |||

{| border=1 | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| with me | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''paho''' | ||

|align=center| with us | |||

|align=center| '''yuaho''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| with us | |||

|align=center| '''wiaho''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| with you | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''giho''' | ||

|align=center| with you (plural) | |||

|align=center| '''jeho''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| with him, with her | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''oho''' | ||

|align=center| with them | |||

|align=center| '''nuho''' | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| with it | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''ʃiho''' | ||

|align=center| with them | |||

|align=center| | |align=center| '''ʃiho''' | ||

|align=center| ''' | |} | ||

=='''-tu''' or '''tù''' '''pilana niapa''' ... (the tenth pilana)== | |||

The instrumental is used for nouns that represent the instrument ("with"), the means ("by"), the agent ("by"), the reason, or the time of an event. | |||

Rāma writes with a pen | |||

baru = to learn, baru.tu = by learning ... without learning ??? ... maybe, maybe | |||

book was written '''patu''' = The book was written by me | |||

hand.tu = manually | |||

I work as a translator ??? ... I work '''sai''' translator ?? | |||

'''tù ta ... ''' | |||

----------------------- | |||

'''tùa''' = to use, to wear ... '''tài''' a SVC meaning ?? .... then '''bai''' | |||

=='''-wo''' or '''wó''' : '''pilana nuata''' ... (the eleventh pilana)== | |||

As well as marking the topic, '''wo''' is also used for marking the "theme" ? as in such sentences as the one below. | |||

'''gala caturi jonowo''' => The women were talking about John | |||

Needless to say that the element '''jonowo''' can not be fronted, well not unless you want to make John the topic. | |||

'''nambowo''' = about the house, concerning the house, with respect to the house | |||

=='''-n''' or '''nà''' : '''pilana najau''' ... (the twelfth pilana)== | |||

Note ... We can have genitives and we can have "genitive phrases". A genitive phrase has no suffix, but the particle '''nà''' must be placed immediately in front of it. | |||

The son of the king => '''sonda blicon''' | |||

The son of the old king => '''sonda nà blico gáu''' | |||

------ | |||

A genitive or a genitive phrase can be considered an adjective. Ownership is also shown by the genitive, however note that when the head is a multi-syllable word and the owner is a stand alone pronoun, then ownership is shown by an infix in the actual head (see "Possessive Infixes"). | |||

------ | |||

Sticking '''-n''' on the end of a noun, is equivalent to sticking the particle "of" in front of a word in English. For example;- | |||

'''fanfa''' = horse | |||

'''sonda''' = son | |||

'''blico''' = king | |||

'''fanfa sondan''' = the horse of the son | |||

'''sonda blicon''' = the son of the king | |||

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle '''na''' must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;- | |||

We can not say '''*fanfa sondan blicon'''. The head of the NP is '''fanfa''' and it is being qualified by two words. So we have to say;- | |||

'''fanfa nà sonda blicon''' | |||

However it is not allowed to use '''nà''' if a suffix can be used. | |||

So we can not say '''*kyolo nà kaunu''' (coat collar) but must say '''kyolo kaunun''' | |||

We can not say '''*kaunu na jene''' (Jane's coat) but must say '''kaunu jenen''' | |||

However if any of these nouns is qualified by an adjective, then '''-n''' can not be suffixed. For example ;- | |||

'''fanfa nà sonda jini blicon''' = "the horse of the king's clever son''' | |||

'''fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua''' = "the horse of the fat king's son" | |||

-------------------------- | |||

This is a special construction that relates pronouns to the '''geladi'''. For example ;- | |||

'''wí''' = to see '''polo''' = Paul '''timpa''' = to hit '''jene''' = Jenny | |||

'''wori polo timpana ''' = He saw paul hitting | |||

'''wori pà timpana ò''' = He saw me hitting her | |||

'''wori jene sana timpi''' = He saw Jenny being hit | |||

'''wori polo timpana jene''' = He saw Paul hitting Jenny | |||

'''wori pás timpa jene''' = He saw me hitting Jenny. | |||

In the above constructions the word order must be as shown above. | |||

=='''-ji''' or '''jí''' : '''pilana najauja''' ... (the thirteenth pilana)== | |||

the benefactor (for) of an event. The dative form of a verb infinitive (which acts like a noun) indicates purpose. | |||

baru = to learn, baruji = in order to learn | |||

So we have '''-ji''' appended to single word NP's. | |||

== ..... 3 participles and 2 complement clauses ... "saidauza" ??== | |||

The name participle is used for an adjective that has been derived from a verb. There are 4 participles in '''béu'''. | |||

Taking '''kludau''' (to write) to demonstrate the these participles. | |||

1) '''kludana''' is an adjective meaning "habitually writing" | |||

'''glabu kludana''' = the writing person ... and following the strong tendency for adjectives to get used as nouns in '''béu''' ... '''kludana''' => author | |||

2) '''kludi''' is an adjective meaning "written" | |||

'''toili kludi''' = the written book ... and following the strong tendency for adjectives to get used as nouns in '''béu''' ... '''kludi''' => a thing that is written => a note | |||

3) '''kluduʒi''' is an adjective meaning "that must be written" | |||

'''toili kluduʒi''' = "the book that must be written" or "the book that should be written" | |||

The usage is the same as English. For example;- | |||

1) I remember that I wrote the book ... all this conveys is "written" rather than "not written" ... takes the same form in '''béu''' ... '''olgara tà kludari toili''' | |||

2) I remember writing the book ... this conveys that the whole process of locking the door is going thru the speakers mind ... '''olgara kludaula toili''' ... basically the same form in Béu and English. | |||

3) I remember to write the book ... A different form in '''béu''' ... '''olgara (tà) toili (rà) kluduʒi''' ... (lock the door is a better example) | |||

------- | |||

To fix up this bit.....Of course we can make two clauses, and have the second clause one element inside the first clause. To do that you must use the particle '''tà'''. Equivalent to one of the uses of "that" in English. '''tà''' basically tells you that the following clause should be treated like a single element, like a single noun. | |||

5) want'''ara tà (gís) timporu òs''' => I want you to hit her ... But why would we use this ... why is 4) not good enough. ...want = wish ...OK if you have '''tà''' it means that your want is actually a wish. | |||

HOW DOES THIS FIT IN WITH THE -ME AND THE -MI FORMS ?? | |||

I should mention '''sá tà ...''' | |||

Note that in 2) and 4), '''gì''' would only be used if emphasis was wanted on "you". | |||

===The saidauza=== | |||

The '''saidauza''' (adjective phrase) is a clause that sets the scene for the main action. | |||

1) "waiting on tables six nights a week", Kirsty had come to know all the regular customers // "their mains flowing", they ran across the field and down to the river. | |||

2) "his leg broken", he slowly crawled up the sand dune and ... | |||

3) "having to pack all the stereos before lunch", he did not stop for a tea-break. | |||

------ | |||

In English grammar, a nominative absolute is a free-standing (absolute) part of a sentence that describes or modifies the main subject and verb. It is usually at the beginning or end of the sentence, although it can also appear in the middle. Its parallel is the ablative absolute in Latin, or the genitive absolute in Greek. | |||

------ | |||

===A discussion of English participles=== | |||

Now English has two participles. One, called the present participle has a meaning that extends over what we express by using 1) and 4). | |||

The other, called the passive participle, corresponds to 3). | |||

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), they do not appear as nouns as in '''béu''', however both are used in verb phrases to extand the shades of meaning that a basic verb can have. If you are a native English speaker and are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. We should go into this a little bit ... first the "active participle" ... | |||

1) The writing man | |||

2) The man is writing | |||

3) The man is writing a book | |||

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense. | |||

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test. | |||

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning). | |||

... now the "passive participle" ... | |||

1) The piano is broken | |||

2) The piano was broken | |||

3) The piano was broken by the monkey | |||

In 1) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense. | |||

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test. | |||

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations<sup>*</sup> when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning). | |||

<sup>*</sup>The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes. | |||

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence. | |||

--------------------------------------- | |||

'''solbe''' = to drink | |||

'''heŋgo''' = to live (or it could mean "a life") | |||

'''soŋkau''' = to die (or it could mean "death") | |||

'''glabu''' = person | |||

'''moʃi''' = water | |||

'''heŋgana''' = alive, living | |||

'''soŋki''' = dead | |||

==R-form of the verb== | |||

Above we have discussed the R-form of the verb. | |||

However there are other verb forms. | |||

While the men are waging war, the women are at home by themselves | |||

men wagURAI war, woman at home by themselves | |||

------ | |||

After their master has ordered it, the slaves begin to work | |||

...AU... ??? | |||

==S-form of the verb== | |||

This form is used for giving orders. With the s-form you definitely want some action to happen (and you don't expect a discussion about it). | |||

Up until now, 7 protagonists have been expressed in every verb. With the s-form however only two protagonists can be expressed. | |||

'''doikis''' = walk (when talking to one person) | |||

'''doikes''' = walk (when talking to more than one person) | |||

Very occasionally the form '''doikas''' is heard. When somebody has difficulty preforming some task the may "order" themselves to do it. | |||

==N-form of the verb== | |||

This is the subjunctive form. You change the "'''r'''" to an '''"n'''" basically. Nothing comes after the "'''n'''". So there is no tense/aspect or evidentiality expressed on this verb form. When the n-form is used in a main clause, it is gently urging some action. For example ;- | |||

'''doikain''' = Let's walk | |||

==ME-form of the verb and the MI-form of a verb== | |||

These tenses are often called the 'conditional', that is, they express a supposition depending on a certain condition. When referring to present time the ME-form is used ; when referring to past time and the condition has no chance of now being realised the MI-form is used. | |||

if know'''ame''' to read buy'''ame''' book => If I knew how to read I would buy a book. | |||

if know'''ami''' to read buy'''ami''' book => If I had known how to read I would have bought a book. | |||

==AI-form of the verb ... jaudauza== | |||

The '''ai'''-form comprises three functions. In the '''béu''' linguistic tradition, these are called "noun-'''ai'''", "verb-'''ai'''" and "small-verb-'''ai'''". | |||

===Major Verb "ai"=== | |||

sing'''ai''' laugh'''ai''' '''loʔura namboʔe''' => They go home singing and laughing | |||

'''loʔura nambo''' sing'''ai''' laugh'''ai''' => They go home singing and laughing | |||

This is used when things happen at the same time and the subject of all the verbs is the same. Notice that the '''ai'''-forms can come before or after the '''r'''-form verb. | |||

This form can not be used when consecutive actions are being described. | |||

===Minor Verb "ai"=== | |||

The small verbs constitute a subset of verbs. They always follow the '''r'''-form verbs. | |||

It is very common to have the following verbs in their ai-form. | |||

'''bià''' means "to stay" | |||

'''bài doikari''' = I was walking | |||

'''bài doikara''' = I am walking | |||

'''bài doikaru''' = I will be walking | |||

The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in '''béu''' anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)". | |||

'''láu''' = to become | |||

I painted the house red = paint'''ari nambo lái hìa''' | |||

----- | |||

'''bwò''' = to receive, to get, to undergo | |||

''' bwaru timpa ''' = I will be hit | |||

'''bài bwài timparu''' = I will be being hit ?? | |||

'''kye''' = to give | |||

'''kyari òye solbe''' | |||

'''(pás) kyari oye timpa glá''' = I made him hit the woman | |||

gain only one verb and it is transitive. There are two ways that we can make an intransitive clause. | |||

1) '''pintu lí mapa''' = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of '''mapa''' and the "copula of becoming" '''láu'''. | |||

Agent => Anything ... It could be that the agent was the wind ... or even some evil spirits ... use your imagination. | |||

2) '''pintu bwori mapau''' = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form. | |||

Agent => Human and the action deliberate ... It strongly implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant. | |||

Let us go back to '''gèu''' and consider '''gèu''' in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways. | |||

1) '''báu lí gèu''' = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of '''gèu''' and the "copula of becoming" '''láu'''. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent. | |||

Agent => Anything and the action could be accidental. | |||

2) '''báu bwori geuldu''' = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant. | |||

Agent => Human and the action deliberate | |||

3) '''báu tí geuldori''' = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved. | |||

Agent => The man and the action deliberate | |||

------ | |||

= to come | |||

= to go | |||

= to rise ... '''sái''' : to raise ... '''slái''' | |||

= to descend ... '''gàu''' : to lower ... '''glàu''' | |||

= to enter ... '''poi''' : to put in ... '''ploi''' | |||

= to go out | |||

= to follow | |||

= to cross | |||

= to go through | |||

= to pass | |||

= to return | |||

= to do something in a haphazard manner, to do something in an unsatisfactory manner | |||

= to scatter about | |||

= to hurry | |||

= to do accidentally ?? | |||

The above are often stuck on the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution. | |||

See what Dixon has in Dyirbal. | |||

'''ai'''-form only with '''r'''-form or can also go with '''n'''-form, etc. etc. | |||

You can add as many verbs as you want. The added verbs are understood to have the same protagonists, '''gwomai''' and evidentiality as the '''r'''-form verb. | |||

pass'''orla''' sing'''ai''' kite '''fly'''ai = He is passing by singing and flying a kite | |||

WHAT ABOUT SEPERATE OBJECTS ON THE TWO VERBS ? | |||

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ??? | |||

== ..... KENKO== | |||

'''keŋko''' = salt ... base form ... noun | |||

'''keŋkua''' = salty ... adjective | |||

'''keŋkia''' = salt-free ... adjective | |||

'''keŋkari''' = I added salt ... verb (transitive) | |||

'''keŋkos''' = to add salt | |||

'''kenkoska''' = to not add salt | |||

== | == Modals== | ||

This word is used for negating the copula '''gaza''' and also for negating the 4 modalities/modals ??? '''nagai''', '''glopai''', '''oldai''' and '''hentai'''. | |||

'''jene oldora humpoko cokolate''' => Jane can '''not''' eat chocolates ... meaning she has the willpower to resist them. | |||

= | '''jene oldorka humpo cokolate''' => Jane can't eat chocolates ... she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet. | ||

'''jene oldorka humpoko cokolate''' => Jane can not not eat chocolates ... meaning she can't resist them. | |||

---------- | |||

Fix this rubbish | |||

''' | '''poma''' = leg | ||

'''pomadu''' = to kick, '''pomari''' = I kicked | |||

= | '''pomuʒi''' = liable to kick, fond of kicking | ||

=== | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| to play | |||

|align=center| '''lento''' | |||

|align=center| playful | |||

|align=center| '''lentuʒi''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| to rest/relax | |||

|align=center| '''loŋge''' | |||

|align=center| lazy | |||

|align=center| '''loŋguʒi''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| to lie | |||

|align=center| '''selne''' | |||

|align=center| untruthful by disposition | |||

|align=center| '''selnuʒi''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| to work | |||

|align=center| '''kodai''' | |||

|align=center| diligent | |||

|align=center| '''koduʒi''' | |||

|} | |||

== | == ..... In, enter, put in== | ||

'''pì''' is a position, a position is a state, a state is an adjective (in '''béu''' anyway) | |||

'''mù''' is a position | |||

------- | |||

'''pìs''' is a verb (to enter) | |||

''' | '''mùs''' is a verb (to exit) | ||

------ | |||

piwai is a verb (to put in) | |||

muau is a verb (to take out) | |||

----- | |||

== .... -MA, and -GO== | |||

=== | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| pronounced | |||

|align=center| operation | |||

|align=center| label | |||

|align=center| example | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''-ma''' | |||

|align=center| adjective => noun | |||

|align=center| "-ness" or "-ity" | |||

|align=center| '''boi.ma''' = goodness | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''-go''' | |||

|align=center| noun => adjective, plus adjective => adjective, plus verb => adjective | |||

|align=center| "ish" | |||

|align=center| '''gla.go''' = effeminate, '''hia.go''' = reddish, '''bla.go''' = quarrelsome | |||

|} | |||

''' | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| '''gèu''' | |||

|align=center| green | |||

|align=center| '''geu.ma''' | |||

|align=center| greenness | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''juga''' | |||

|align=center| wide | |||

|align=center| '''juga.ma''' | |||

|align=center| width | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''tumu''' | |||

|align=center| stupid | |||

|align=center| '''tumu.ma''' | |||

|align=center| stupidity | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''bòi''' | |||

|align=center| good | |||

|align=center| '''boi.ma''' | |||

|align=center| goodness | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''mutu''' | |||

|align=center| important | |||

|align=center| '''mutu.ma''' | |||

|align=center| importance | |||

|} | |||

''' | '''-go''' | ||

''' | '''gó''' = to resemble, to be like | ||

''' | '''gó dó''' = to be the exact image of | ||

''' | '''gla.go''' = effeminate, '''hia.go''' = reddish, '''bla.go''' = quarrelsome | ||

''' | Sometimes the '''-go''' derived words have negative connotations, as in '''gal.go''' | ||

There is a suffix '''-ka''' (notice it is not considered a '''pilana'''), that often has a positive connotation, sometimes making a couplet with a '''-go''' derived word. For example ;- | |||

''' | '''gla.ka''' = womanly | ||

''' | '''kài''' = to appear, to seem | ||

= | '''kò''' = appearance | ||

= | ==Beyond the simple clause== | ||

OK we have simple clauses such as ;- | |||

= | '''donoru''' = She will walk ... intransitive | ||

'''(ós) timpori pà''' = She hit me ... transitive | |||

But often things are more complicated. First consider the verb "want". | |||

When the object is a noun, we have a simple clause. But what if there is another verb in there. For example "I want to go home" | |||

''' | Well this would use the '''gelada''' form of "go" ;- | ||

''' | 1) want'''ara dono nambye''' => I want to walk home .... The same as in English. | ||

But what if we have different subjects. Well we would use the subjunctive form of the verb "to walk" ;- | |||

''' | 2) want'''ara (gì) donin nambye''' => I want you to walk home (I have to go back and change the forms of the verb ?? subjuctive used to be "s" not "n", now "s" is imperative ??)) | ||

... notice that we do not use the infinitive as in English. | |||

What about making things more complicated and having a transitive verb. | |||

= | 3) want'''ara timpa òs''' => I want to hit her ... (word order important or not ??) | ||

= | 4) want'''ara (gì) timpin òs''' => I want you to hit her | ||

Now we have said before that '''béu''' has free word order, however this really only applies to the verb in R-form (R) and the S argument in an intransitive clause, and the R, A and O in a transitive clause. When you have a verb in '''geladi'''-form (G), in the subjunctive form (N) or in the imperative form (I), you must have these elements in the following order ;- | |||

S G : S N ... the last of these (S -S ) is quite unusual. Maybe can have S I ... but then S must be in vocative case | |||

A G O : A N O : I O ... expand this and make it look good. Maybe can have A I O ... but then A must be in vocative case | |||

----- | |||

In the '''béu''' linguistic tradition, a clause that has one R verb in it, or one N verb, or one I verb is called '''aʒiŋko baga''' or a simple clause. Any clause that has an R verb plus an G or N, verb is called a '''aʒiŋko kaza''' or a complex clause. | |||

== | ==..... Getting the opposite by adding "u"== | ||

=== | ===.... A prefix for adjectives=== | ||

''' | '''taitau''' = many | ||

= | '''utaitau''' = few | ||

= | '''mutu''' = important | ||

= | '''umutu''' = unimportant | ||

===.... and a prefix for adverb=== | |||

'''nan''' = for a long time | |||

'''unan''' = not for a long time | |||

===.... and a prefix for nouns=== | |||

''' | '''mezna''' = to fight | ||

'''meznana''' = combatant | |||

'''umeznana''' = non-combatant | |||

As in English, not found that often. Sometimes found in rule books. | |||

===.... but an infix for verbs=== | |||

There is a reason why we do not simply prefix '''u''' to the verbs also. | |||

'''kanja''' = to fold | |||

'''kunjana''' = "folding" (an adjective) or "one that folds" (a noun) | |||

''' | '''ukunjana''' = "one that doesn't fold" | ||

''' | Suppose we did simply prefix '''u''' to the verb. Then "to unfold" would be '''ukanja''', and hence '''ukanjana''' would be a noun meaning "one that unfolds". But if you look up a bit, you can see that this form ('''ukanjana''') already has the meaning "one that doesn't fold". This would cause confusion. | ||

=== | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| '''kunja''' | |||

|align=center| to fold | |||

|align=center| '''kunjua''' | |||

|align=center| to unfold | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''laiba''' | |||

|align=center| to cover | |||

|align=center| '''laibua''' | |||

|align=center| to uncover | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''fuŋga''' | |||

|align=center| to fasten, to lock | |||

|align=center| '''fuŋgua''' | |||

|align=center| to unfasten, to unlock | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''benda''' | |||

|align=center| to assemble, to put together | |||

|align=center| '''bendua''' | |||

|align=center| to take apart, to disassemble | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''pauca''' | |||

|align=center| to stop up, to block | |||

|align=center| '''paucua''' | |||

|align=center| to unstop | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''sensa''' | |||

|align=center| to weave | |||

|align=center| '''sensua''' | |||

|align=center| to unravel | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''fiŋka''' | |||

|align=center| to put on clothes, to dress | |||

|align=center| '''fiŋkua''' | |||

|align=center| to undress | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''tasta''' | |||

|align=center| to tangle | |||

|align=center| '''tastua''' | |||

|align=center| to untangle | |||

|} | |||

Note that in any other form but the '''geladi''', the '''u''' changes to a '''w'''. For example ;- | |||

'''fiŋkwori''' = he undressed | |||

==The time of day== | |||

= | '''dé''' = day | ||

The '''béu''' day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called '''cuaju''' | |||

The time of day is counted from '''cuaju'''. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called '''ajai''' (normally just called '''ajai''', but '''cúa ajai''' or '''ajai yanfa''' might also be heard sometimes). | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| 6 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''cuaju''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 8 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''ajai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''uvai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| midday | |||

|align=center| '''ibai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | |||

|align=center| '''agai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | |||

|align=center| '''idai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 6 o'clock in the evening | |||

|align=center| '''ulai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 8 o'clock in the evening | |||

|align=center| '''icai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 o'clock at night | |||

|align=center| '''ezai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| midnight | |||

|align=center| '''okai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''apai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''atai''' | |||

|} | |||

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon. | |||

16:00 would be '''idai''' : 16:10 would be '''idaijau''' : 16:20 would be '''idaivau''' .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be '''idaitau | |||

Now all these names have in common the element '''idai''', hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called '''idaia''' (the plural of '''idai'''). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties". | |||

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called '''cuajua'''. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time '''ajai''' was called '''ajaia'''(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time '''cuaju''' should be called '''cuajua'''. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial '''cuaju'''. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be '''cuaju ajau''', "twenty past six" would be '''cuaju avau''' and so on. | |||

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened '''idaia.pi''' | |||

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them '''apaiʔe'''. | |||

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued '''nàn uvau''', for 2 hours : '''nàn ajai''' ('''nàn''' means "a long time") | |||

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In '''béu''' they only have the '''yanfa'''. The '''yanfa''' is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as '''yanfa''' also. | |||

== The town clock == | |||

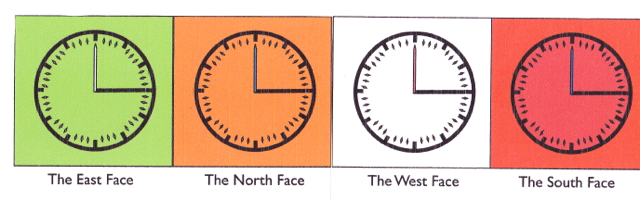

Every town has a clocktower and the clocktower has 4 faces, which are aligned with the cardinal directions. The street pattern is also so aligned : that is the four biggest streets radiate out from the clock in the cardinal directions. | |||

Each face displaying a clock similar to the one below. | |||

[[Image:TW_93.png]] | |||

The above figure shows the time at exactly 6 in the morning. You notice that the main (hour hand) hand is pointing to the right : it starts from the horizontal. This hand sweeps out one revolution in 24 hours and it moves anti-clockwise | |||

Notice that secondary (minute hand) starts from the vertical and sweeps out a revolution in 2 of our hours. It moves clockwise. And actually when it passes the main hand, there is a clever mechanism to stop it being hidden. It stops 3.75 minutes at one side of the main hand, and then moves directly (2 steps) to the other side of the main hand and stops there for 3.75 minutes. After that it does a step and waits 2.5 minutes, etc. etc. ... until it encounters the main hand again. | |||

The red and the black arms do not move continuously but move in steps. The primary arm moves 3.75 degrees every 15 minutes, and the secondary arm moves 7.5 degrees every 2.5 minutes. | |||

The clocktower is surmounted by a green conic roof (actually not really conic ... the roof slope decreases as you get nearer the bottom). Lighting from under the roof could be provided for each face. Either that or the faces could be illuminated from within at night. The faces are not exactly vertical but the top slightly overhangs the bottom. | |||

There is never any numbering on the face. | |||

The clock also emits sounds. Every 2 of our hours the clock makes a deep "boing" which reverberates for some time. Also from 6 in the morning to 6 at night, the clock emits a "boing" every 30 of our minutes. The first "boing" has no accompaniment. However the second "boing" is followed (well actually when the "boing" is only .67 % dissipated) by a "sharper" sound that dies down a lot quicker : "teen". The third "boing" has 2 "teen"s 0.72 seconds apart. The fourth has 3 "teen"s. The fifth one is back to the single "boing" and so it continues thru the day. | |||

The secondary hand and the 36 diamonds should be ... | |||

East face => white or even better, silver | |||

North face => light blue | |||

West face => green | |||

South face => dark blue | |||

(The drawing is a bit out in this respect). | |||

==Index== | ==Index== | ||

{{Béu Index}} | {{Béu Index}} | ||

Revision as of 21:55, 8 October 2012

-ho or hò : pilana noka ... (the ninth pilana)

"in the company of", often used with the personal pronouns ;-

| with me | paho | with us | yuaho |

| with us | wiaho | ||

| with you | giho | with you (plural) | jeho |

| with him, with her | oho | with them | nuho |

| with it | ʃiho | with them | ʃiho |

-tu or tù pilana niapa ... (the tenth pilana)

The instrumental is used for nouns that represent the instrument ("with"), the means ("by"), the agent ("by"), the reason, or the time of an event.

Rāma writes with a pen

baru = to learn, baru.tu = by learning ... without learning ??? ... maybe, maybe

book was written patu = The book was written by me

hand.tu = manually

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sai translator ??

tù ta ...

tùa = to use, to wear ... tài a SVC meaning ?? .... then bai

-wo or wó : pilana nuata ... (the eleventh pilana)

As well as marking the topic, wo is also used for marking the "theme" ? as in such sentences as the one below.

gala caturi jonowo => The women were talking about John

Needless to say that the element jonowo can not be fronted, well not unless you want to make John the topic.

nambowo = about the house, concerning the house, with respect to the house

-n or nà : pilana najau ... (the twelfth pilana)

Note ... We can have genitives and we can have "genitive phrases". A genitive phrase has no suffix, but the particle nà must be placed immediately in front of it.

The son of the king => sonda blicon

The son of the old king => sonda nà blico gáu

A genitive or a genitive phrase can be considered an adjective. Ownership is also shown by the genitive, however note that when the head is a multi-syllable word and the owner is a stand alone pronoun, then ownership is shown by an infix in the actual head (see "Possessive Infixes").

Sticking -n on the end of a noun, is equivalent to sticking the particle "of" in front of a word in English. For example;-

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blicon = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can not say *fanfa sondan blicon. The head of the NP is fanfa and it is being qualified by two words. So we have to say;-

fanfa nà sonda blicon

However it is not allowed to use nà if a suffix can be used.

So we can not say *kyolo nà kaunu (coat collar) but must say kyolo kaunun

We can not say *kaunu na jene (Jane's coat) but must say kaunu jenen

However if any of these nouns is qualified by an adjective, then -n can not be suffixed. For example ;-

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

This is a special construction that relates pronouns to the geladi. For example ;-

wí = to see polo = Paul timpa = to hit jene = Jenny

wori polo timpana = He saw paul hitting

wori pà timpana ò = He saw me hitting her

wori jene sana timpi = He saw Jenny being hit

wori polo timpana jene = He saw Paul hitting Jenny

wori pás timpa jene = He saw me hitting Jenny.

In the above constructions the word order must be as shown above.

-ji or jí : pilana najauja ... (the thirteenth pilana)

the benefactor (for) of an event. The dative form of a verb infinitive (which acts like a noun) indicates purpose.

baru = to learn, baruji = in order to learn

So we have -ji appended to single word NP's.

..... 3 participles and 2 complement clauses ... "saidauza" ??

The name participle is used for an adjective that has been derived from a verb. There are 4 participles in béu.

Taking kludau (to write) to demonstrate the these participles.

1) kludana is an adjective meaning "habitually writing"

glabu kludana = the writing person ... and following the strong tendency for adjectives to get used as nouns in béu ... kludana => author

2) kludi is an adjective meaning "written"

toili kludi = the written book ... and following the strong tendency for adjectives to get used as nouns in béu ... kludi => a thing that is written => a note

3) kluduʒi is an adjective meaning "that must be written"

toili kluduʒi = "the book that must be written" or "the book that should be written"

The usage is the same as English. For example;-

1) I remember that I wrote the book ... all this conveys is "written" rather than "not written" ... takes the same form in béu ... olgara tà kludari toili

2) I remember writing the book ... this conveys that the whole process of locking the door is going thru the speakers mind ... olgara kludaula toili ... basically the same form in Béu and English.

3) I remember to write the book ... A different form in béu ... olgara (tà) toili (rà) kluduʒi ... (lock the door is a better example)

To fix up this bit.....Of course we can make two clauses, and have the second clause one element inside the first clause. To do that you must use the particle tà. Equivalent to one of the uses of "that" in English. tà basically tells you that the following clause should be treated like a single element, like a single noun.

5) wantara tà (gís) timporu òs => I want you to hit her ... But why would we use this ... why is 4) not good enough. ...want = wish ...OK if you have tà it means that your want is actually a wish.

HOW DOES THIS FIT IN WITH THE -ME AND THE -MI FORMS ??

I should mention sá tà ...

Note that in 2) and 4), gì would only be used if emphasis was wanted on "you".

The saidauza

The saidauza (adjective phrase) is a clause that sets the scene for the main action.

1) "waiting on tables six nights a week", Kirsty had come to know all the regular customers // "their mains flowing", they ran across the field and down to the river.

2) "his leg broken", he slowly crawled up the sand dune and ...

3) "having to pack all the stereos before lunch", he did not stop for a tea-break.

In English grammar, a nominative absolute is a free-standing (absolute) part of a sentence that describes or modifies the main subject and verb. It is usually at the beginning or end of the sentence, although it can also appear in the middle. Its parallel is the ablative absolute in Latin, or the genitive absolute in Greek.

A discussion of English participles

Now English has two participles. One, called the present participle has a meaning that extends over what we express by using 1) and 4).

The other, called the passive participle, corresponds to 3).

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), they do not appear as nouns as in béu, however both are used in verb phrases to extand the shades of meaning that a basic verb can have. If you are a native English speaker and are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. We should go into this a little bit ... first the "active participle" ...

1) The writing man

2) The man is writing

3) The man is writing a book

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

... now the "passive participle" ...

1) The piano is broken

2) The piano was broken

3) The piano was broken by the monkey

In 1) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations* when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

*The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes.

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence.

solbe = to drink

heŋgo = to live (or it could mean "a life")

soŋkau = to die (or it could mean "death")

glabu = person

moʃi = water

heŋgana = alive, living

soŋki = dead

R-form of the verb

Above we have discussed the R-form of the verb.

However there are other verb forms.

While the men are waging war, the women are at home by themselves

men wagURAI war, woman at home by themselves

After their master has ordered it, the slaves begin to work

...AU... ???

S-form of the verb

This form is used for giving orders. With the s-form you definitely want some action to happen (and you don't expect a discussion about it).

Up until now, 7 protagonists have been expressed in every verb. With the s-form however only two protagonists can be expressed.

doikis = walk (when talking to one person)

doikes = walk (when talking to more than one person)

Very occasionally the form doikas is heard. When somebody has difficulty preforming some task the may "order" themselves to do it.

N-form of the verb

This is the subjunctive form. You change the "r" to an "n" basically. Nothing comes after the "n". So there is no tense/aspect or evidentiality expressed on this verb form. When the n-form is used in a main clause, it is gently urging some action. For example ;-

doikain = Let's walk

ME-form of the verb and the MI-form of a verb

These tenses are often called the 'conditional', that is, they express a supposition depending on a certain condition. When referring to present time the ME-form is used ; when referring to past time and the condition has no chance of now being realised the MI-form is used.

if knowame to read buyame book => If I knew how to read I would buy a book.

if knowami to read buyami book => If I had known how to read I would have bought a book.

AI-form of the verb ... jaudauza

The ai-form comprises three functions. In the béu linguistic tradition, these are called "noun-ai", "verb-ai" and "small-verb-ai".

Major Verb "ai"

singai laughai loʔura namboʔe => They go home singing and laughing

loʔura nambo singai laughai => They go home singing and laughing

This is used when things happen at the same time and the subject of all the verbs is the same. Notice that the ai-forms can come before or after the r-form verb.

This form can not be used when consecutive actions are being described.

Minor Verb "ai"

The small verbs constitute a subset of verbs. They always follow the r-form verbs.

It is very common to have the following verbs in their ai-form.

bià means "to stay"

bài doikari = I was walking

bài doikara = I am walking

bài doikaru = I will be walking

The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in béu anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)".

láu = to become

I painted the house red = paintari nambo lái hìa

bwò = to receive, to get, to undergo

bwaru timpa = I will be hit

bài bwài timparu = I will be being hit ??

kye = to give

kyari òye solbe

(pás) kyari oye timpa glá = I made him hit the woman

gain only one verb and it is transitive. There are two ways that we can make an intransitive clause.

1) pintu lí mapa = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu.

Agent => Anything ... It could be that the agent was the wind ... or even some evil spirits ... use your imagination.

2) pintu bwori mapau = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate ... It strongly implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant.

Let us go back to gèu and consider gèu in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways.

1) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Agent => Anything and the action could be accidental.

2) báu bwori geuldu = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate

3) báu tí geuldori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved.

Agent => The man and the action deliberate

= to come

= to go

= to rise ... sái : to raise ... slái

= to descend ... gàu : to lower ... glàu

= to enter ... poi : to put in ... ploi

= to go out

= to follow

= to cross

= to go through

= to pass

= to return

= to do something in a haphazard manner, to do something in an unsatisfactory manner

= to scatter about

= to hurry

= to do accidentally ??

The above are often stuck on the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution.

See what Dixon has in Dyirbal.

ai-form only with r-form or can also go with n-form, etc. etc.

You can add as many verbs as you want. The added verbs are understood to have the same protagonists, gwomai and evidentiality as the r-form verb.

passorla singai kite flyai = He is passing by singing and flying a kite

WHAT ABOUT SEPERATE OBJECTS ON THE TWO VERBS ?

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ???

..... KENKO

keŋko = salt ... base form ... noun

keŋkua = salty ... adjective

keŋkia = salt-free ... adjective

keŋkari = I added salt ... verb (transitive)

keŋkos = to add salt

kenkoska = to not add salt

Modals

This word is used for negating the copula gaza and also for negating the 4 modalities/modals ??? nagai, glopai, oldai and hentai.

jene oldora humpoko cokolate => Jane can not eat chocolates ... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jene oldorka humpo cokolate => Jane can't eat chocolates ... she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jene oldorka humpoko cokolate => Jane can not not eat chocolates ... meaning she can't resist them.

Fix this rubbish

poma = leg

pomadu = to kick, pomari = I kicked

pomuʒi = liable to kick, fond of kicking

| to play | lento | playful | lentuʒi |

| to rest/relax | loŋge | lazy | loŋguʒi |

| to lie | selne | untruthful by disposition | selnuʒi |

| to work | kodai | diligent | koduʒi |

..... In, enter, put in

pì is a position, a position is a state, a state is an adjective (in béu anyway)

mù is a position

pìs is a verb (to enter)

mùs is a verb (to exit)

piwai is a verb (to put in)

muau is a verb (to take out)

.... -MA, and -GO

| pronounced | operation | label | example |

| -ma | adjective => noun | "-ness" or "-ity" | boi.ma = goodness |

| -go | noun => adjective, plus adjective => adjective, plus verb => adjective | "ish" | gla.go = effeminate, hia.go = reddish, bla.go = quarrelsome |

| gèu | green | geu.ma | greenness |

| juga | wide | juga.ma | width |

| tumu | stupid | tumu.ma | stupidity |

| bòi | good | boi.ma | goodness |

| mutu | important | mutu.ma | importance |

-go

gó = to resemble, to be like

gó dó = to be the exact image of

gla.go = effeminate, hia.go = reddish, bla.go = quarrelsome

Sometimes the -go derived words have negative connotations, as in gal.go

There is a suffix -ka (notice it is not considered a pilana), that often has a positive connotation, sometimes making a couplet with a -go derived word. For example ;-

gla.ka = womanly

kài = to appear, to seem

kò = appearance

Beyond the simple clause

OK we have simple clauses such as ;-

donoru = She will walk ... intransitive

(ós) timpori pà = She hit me ... transitive

But often things are more complicated. First consider the verb "want".

When the object is a noun, we have a simple clause. But what if there is another verb in there. For example "I want to go home"

Well this would use the gelada form of "go" ;-

1) wantara dono nambye => I want to walk home .... The same as in English.

But what if we have different subjects. Well we would use the subjunctive form of the verb "to walk" ;-

2) wantara (gì) donin nambye => I want you to walk home (I have to go back and change the forms of the verb ?? subjuctive used to be "s" not "n", now "s" is imperative ??))

... notice that we do not use the infinitive as in English.

What about making things more complicated and having a transitive verb.

3) wantara timpa òs => I want to hit her ... (word order important or not ??)

4) wantara (gì) timpin òs => I want you to hit her

Now we have said before that béu has free word order, however this really only applies to the verb in R-form (R) and the S argument in an intransitive clause, and the R, A and O in a transitive clause. When you have a verb in geladi-form (G), in the subjunctive form (N) or in the imperative form (I), you must have these elements in the following order ;-

S G : S N ... the last of these (S -S ) is quite unusual. Maybe can have S I ... but then S must be in vocative case

A G O : A N O : I O ... expand this and make it look good. Maybe can have A I O ... but then A must be in vocative case

In the béu linguistic tradition, a clause that has one R verb in it, or one N verb, or one I verb is called aʒiŋko baga or a simple clause. Any clause that has an R verb plus an G or N, verb is called a aʒiŋko kaza or a complex clause.

..... Getting the opposite by adding "u"

.... A prefix for adjectives

taitau = many

utaitau = few

mutu = important

umutu = unimportant

.... and a prefix for adverb

nan = for a long time

unan = not for a long time

.... and a prefix for nouns

mezna = to fight

meznana = combatant

umeznana = non-combatant

As in English, not found that often. Sometimes found in rule books.

.... but an infix for verbs

There is a reason why we do not simply prefix u to the verbs also.

kanja = to fold

kunjana = "folding" (an adjective) or "one that folds" (a noun)

ukunjana = "one that doesn't fold"

Suppose we did simply prefix u to the verb. Then "to unfold" would be ukanja, and hence ukanjana would be a noun meaning "one that unfolds". But if you look up a bit, you can see that this form (ukanjana) already has the meaning "one that doesn't fold". This would cause confusion.

| kunja | to fold | kunjua | to unfold |

| laiba | to cover | laibua | to uncover |

| fuŋga | to fasten, to lock | fuŋgua | to unfasten, to unlock |

| benda | to assemble, to put together | bendua | to take apart, to disassemble |

| pauca | to stop up, to block | paucua | to unstop |

| sensa | to weave | sensua | to unravel |

| fiŋka | to put on clothes, to dress | fiŋkua | to undress |

| tasta | to tangle | tastua | to untangle |

Note that in any other form but the geladi, the u changes to a w. For example ;-

fiŋkwori = he undressed

The time of day

dé = day

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | uvai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaivau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju avau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn uvau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

The town clock

Every town has a clocktower and the clocktower has 4 faces, which are aligned with the cardinal directions. The street pattern is also so aligned : that is the four biggest streets radiate out from the clock in the cardinal directions.

Each face displaying a clock similar to the one below.

The above figure shows the time at exactly 6 in the morning. You notice that the main (hour hand) hand is pointing to the right : it starts from the horizontal. This hand sweeps out one revolution in 24 hours and it moves anti-clockwise

Notice that secondary (minute hand) starts from the vertical and sweeps out a revolution in 2 of our hours. It moves clockwise. And actually when it passes the main hand, there is a clever mechanism to stop it being hidden. It stops 3.75 minutes at one side of the main hand, and then moves directly (2 steps) to the other side of the main hand and stops there for 3.75 minutes. After that it does a step and waits 2.5 minutes, etc. etc. ... until it encounters the main hand again.

The red and the black arms do not move continuously but move in steps. The primary arm moves 3.75 degrees every 15 minutes, and the secondary arm moves 7.5 degrees every 2.5 minutes.

The clocktower is surmounted by a green conic roof (actually not really conic ... the roof slope decreases as you get nearer the bottom). Lighting from under the roof could be provided for each face. Either that or the faces could be illuminated from within at night. The faces are not exactly vertical but the top slightly overhangs the bottom.

There is never any numbering on the face.

The clock also emits sounds. Every 2 of our hours the clock makes a deep "boing" which reverberates for some time. Also from 6 in the morning to 6 at night, the clock emits a "boing" every 30 of our minutes. The first "boing" has no accompaniment. However the second "boing" is followed (well actually when the "boing" is only .67 % dissipated) by a "sharper" sound that dies down a lot quicker : "teen". The third "boing" has 2 "teen"s 0.72 seconds apart. The fourth has 3 "teen"s. The fifth one is back to the single "boing" and so it continues thru the day.

The secondary hand and the 36 diamonds should be ...

East face => white or even better, silver

North face => light blue

West face => green

South face => dark blue

(The drawing is a bit out in this respect).

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences