Béu : Chapter 1: Difference between revisions

| Line 920: | Line 920: | ||

==... Parts of speech and word order ... part 1== | ==... Parts of speech and word order ... part 1== | ||

The main parts of speech in '''béu''' are nouns, verbs | The main parts of speech in '''béu''' are nouns, adjectives and verbs (there are also particles but they are a mixed bag, it is hard to generalise about them). However we can generalise about nouns, adjectives and verbs. Nouns (N), adjectives (A) and verbs (V) are called "parts of speech". In this section we are going to talk about how a word can changed its part of speech. Sometimes a word can be a member of 2 or 3 different parts of speech without changing its form, sometimes a change of form is necessary ... typically an affix is added. For convenience I am going to introduce another type of word called '''geladi''' (G), this is the infinitive form of the verb. This is the "base form" of the verb and it resembles a noun in many respects(but not in everyway). In English the infinitive form is usually preceded by "to". | ||

Let us take the word '''gèu''' "green" | For example '''solbe''' means "to drink" and is a '''geladi''' (G). But more often you find this word in other forms. For example if you came across '''solbarin''' which means "I drank, so they say". I am counting the form '''solbarin''' as a verb (V), and the form '''solbe''' as a '''geladi'''. That is I am treating them as different parts of speech. This is just for convenience. I do not want to get into an argument about linguistic theories etc. etc. This is just to make things easy to discuss. | ||

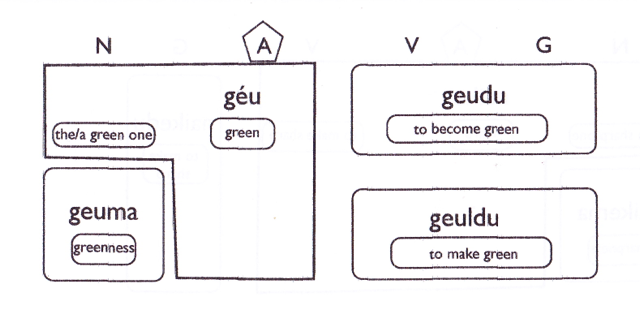

Let us start of with a single syllable adjective and see what "forms" single syllable adjective can take and what "parts of speech" these forms can belong to. Let us take the word '''gèu''' "green" ;- | |||

[[Image:TW_81.png]] | |||

Along the top of the above chart you can see N, A, V and G. These are different part of speech. The form under these 4 headings, shows the form '''géu''' takes when it is one of these 4 parts of speech. Now '''géu''' is fundamentally an adjective ... that is what that pentangle around the "A" means. In the above chart we can see that an unmodified '''géu''' can also function as a noun sometimes. When it acts as a noun it would mean "the/a green one". But how can we tell if '''géu''' is representing a noun or an adjective. Well we can tell by the position of '''gèu''' with respect to other elements in the clause. | |||

'''gèu''' is an adjective if it comes immediately after the copula '''sàu'''. For example '''báu rì gèu''' => The/a man was green. | '''gèu''' is an adjective if it comes immediately after the copula '''sàu'''. For example '''báu rì gèu''' => The/a man was green. | ||

'''gèu''' is also an adjective if it comes immediately after a noun i.e. '''báu gèu dí''' => This green man * | '''gèu''' is also an adjective if it comes immediately after a noun i.e. '''báu gèu dí''' => This green man * | ||

In other positions '''géu''' represents a noun. | |||

We can see that we can derive two verbs from '''géu'''. By affixing '''-du''' we get an intransitive verb meaning "to become green". And by affixing '''-ldu''' we get an transitive verb meaning "to make green". You can see that the '''V'''-forms and the '''G'''-forms are the same. | |||

To make a "finite" verb, i.e. what I call V from the G form, it is always the same process. First you delete the final vowel, then you add a vowel that represents the subject, then you add, either '''r''', '''n''' or '''s''' (depending if you want the indicative mood, the subjunctive nood or the imperative), then you add a vowel (or consonant + vowel) which is the tense/aspect marker followed by an optional evidential marker '''n''', '''s''' or '''a'''. So we could get '''geud<del>u</del>''' + '''i''' + '''r''' + '''i''' +'''a''' => '''geudiria''' = "you became green, I saw it." | |||

You can see that two nouns are made from '''géu'''. Well one does not change its form, I call this one "the substantive noun", i.e. "the green one". The other changes its form by taking an affix. I call this one "the qualitative noun", i.e. "greenness". | |||

OK. | |||

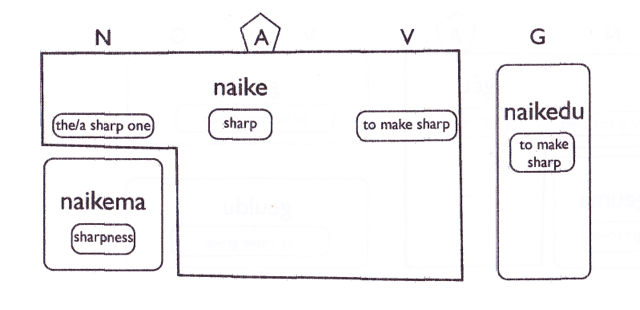

[[Image:TW_82.png]] | |||

'''gèu''' is a qualitative noun if it comes immediately after the copula '''gaza''' i.e. '''ʔá pona''' => It is cold ..... | '''gèu''' is a qualitative noun if it comes immediately after the copula '''gaza''' i.e. '''ʔá pona''' => It is cold ..... | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 16 September 2012

..... The sounds of béu

The full range of sounds heard in béu are given below according to the conventions of the I.P.A. (International Phonetic Alphabet)

| labial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | |||

| fricatives | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | h | |||

| affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| liquids | r l | ||||||

| glides | w | y |

tʃ dʒ are the initial sounds of "Charlie" and "Jimmy" respectively. From now on they will be represented by c and j.

ʔ represents a glottal stop (the sound a cockney would make when he drops the "tt" in bottle). In béu this is a normal consonant ... just as real as "b" or "g" in English.

v is an allophone of f when inside a word and between two vowels.

z is an allophone of s when inside a word and between two voiced* sounds.

ʃ is also an allophone of s when before the front vowel i or before the consonant y. ʃ is found in English and is usually represented by "sh" (as in "shell")

ʒ is an allophone of s when the above two conditions apply at the same time. ʒ turns up in English in one or two words. It is the middle consonant in the word "pleasure".

ŋ is an allophone of n when followed by k or g. ŋ is found in English and is usually represented by "ng" (as in "sing").

l is a clear lateral in all environments.

r is an approximant in all environments.

p, t and k are never aspirated. And on the other hand b, d and g are more voiced than in English (i.e. the voice onset time is a lot earlier)

* Actually all the phonemes are voiced, apart from p, t, k, s, h and ʔ.

The béu phoneme inventory is shown below.

| labial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | |||

| fricatives | f | s | h | ||||

| affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| nasals | m | n | |||||

| liquids | r l | ||||||

| glides | w | y |

The basic vowels are a, e, i, o and u. Also the diphthongs ai, au, oi, eu, ia and ua are used. Note that while the sounds ia and ua are possible sound combinations in English, they each are realised as two syllables. In béu the two components are more intertwined ... the flow into each other more. And they each represent only one syllable.

It has been reported that béu stresses the second to last syllable in a word. However this is untrue. This report came about because béu speakers pronounce the second to last syllable of AN UTTERANCE, louder. This lead some linguistic field workers who were elicitating single words from the béu speakers, to draw the wrong conclusions.

béu differentiates between words using tone. All single syllable words have either a high tone (for example pás = "I") or a low tone (for example pà = me). All multi-syllable words lack tone (or can be said to have neutral tone). If a single syllable word, receives an affix making it into a multi-syllable word, its tone will become neutralised. If a word count was done on a typical béu text, it would be found that around 17% of words have a high tone, 33% have a low tone and 50% have the neutral tone.

Don't let the tones put you off learning béu. The chances are vanishingly small that you will cause a misunderstanding by pronouncing one of the short words wrong. And even if you speak the language and put absolutely no effort into getting the tones right ... no problem, it will just mark you out as a non-native speaker ... but who isn't :-)

I am representing the high tone with a full-stop sign after the syllable (in a similar manner the béu writing system places a small dot to the right of a high tone syllable). If single syllable words are come across that are not followed by a full-stop, they can be taken as low-tone (as happens in the native béu writing system).

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "allophone", "voiced sound" and "diphthong" are linguistic jargon. You don't have to worry if you don't understand what they mean.

..... Some interjections

All languages have a small set of interjections. Usually they party fall outside the normal sound system rules. béu is no exception.

iʃʃ ... an exclamation expressing sympathy (neutral tone)

xaa ... an exclamation of disgust (it starts of as a neutral tone, falls quickly then sort of lingers at a low level)...(the "x" represents the last sound in "loch")

aido ... an exclamation of frustration (rapidly rising tone on the "ai", a short break, then the "do" is a lowish level tone)

oho ... an exclamation of awe ("o" is a normal high tone, "ho" starts quite high and rises to the normal high tone level)

..... Consonant clusters

The following consonants and consonant clusters can begin a word;-

| ʔ | |||

| m | my | ||

| y | |||

| j | jw | ||

| f | fy | fl | |

| b | by | bl | bw |

| g | gl | gw | |

| d | dw | ||

| l | |||

| c | cw | ||

| s/ʃ | sl | sw | |

| k | ky | kl | kw |

| p | py | pl | |

| t | tw | ||

| w | |||

| n | ny | ||

| h |

The following consonants and consonant clusters can be found in the middle of a word;-

| l@ | lm | ly | lj | lf | lb | lg | ld | lc | lz/lʒ | lk | lp | lt | lw | ln | lh | |

| @ | m | y | j | v | b | g | d | l | c | z/ʒ | k | p | t | w | n | h |

| n@ | ny | nj | nf | mb | ŋg | nd | nc | nz/nʒ | ŋk | mp | nt | mw | nh | |||

| s@ | zm | ʒy | zb | zg | zd | zl | sk | sp | st | zw | zn | sh |

The consonants n and s can occur word finally.

..... Plurals and duals

In béu the basic noun is undefined as to number. For example the plain noun báu could refer to any number of men. You can optionally use the plural form bawa to indicate a number more than one. To unequivocally refer to just one man, the word aba "one" must be included. i.e. aja báu = one man

báu = man or men

aja báu = one man

bawa = men

Most nouns end in one of the vowels a i u e or o.

To make a plural, these vowels undergo the following transformation.

a => ai

i => ia

u => ua

e => eu

o => oi

There are 8 nouns (that name parts of the body) that have a dual form as well as a plural form. They are ;-

wá = eye

elza = ear

duva = arm or hand

poma = leg or foot

gluma = breast

jwuba = buttock

ploka = cheek

olna = shoulder

The dual form is made by a => au. For these 8 words the plural form means "3 or more" as opposed to "2 or more".

Also there are some other word that have a dual.

glabu = person

glabua = people

glabau = a couple (not necessary married but the word gives a very strong connotation that the couple are intimate/having sexual relations)

kloga = shoe

klogau = a pair of shoes

A very small number of nandau end in ai or au. For plurality they take a(that is another syllable is added to the word). For example ;-

nandau = word, nandaua = words

moltai = doctor, moltaia = doctors

At least 3 single-syllable words have irregular plurals. These are ;-

glà = woman

gala = women

báu = man

bawa = men

Usually single-syllable words indicate plurality by having nò in front.

nò = number ... actually this is one of the few single-syllable nouns that creates its plural in the same way as multi-syllable nouns ... nòi = numbers

..... Thread Writing

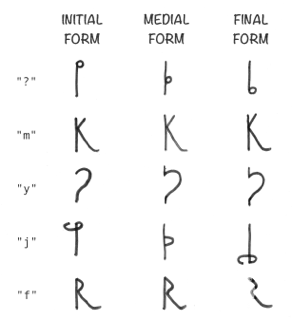

béu has 17 consonants.

For some of these the form differs slightly, depending upon whether the letter is at word initial, word medial or word final.

The three forms are shown below.

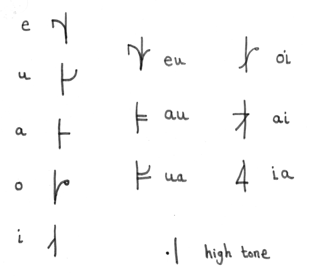

béu has 5 vowels and 6 diphthongs.

The form of these doesn't change.

These are shown below.

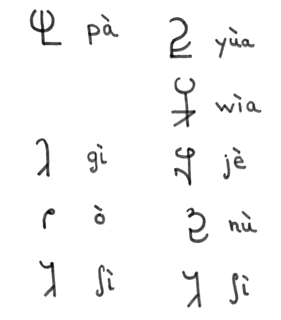

To give you better idea of what thread writing looks like, I have listed below the 12 colours of béu.

Nice, eh? Sort of organic.

..... Numbers

béu uses base 12.

| one | aja | 1012 | ajau | 10012 | ajai |

| two | auva | 2012 | uvau | 20012 | uvai |

| three | aiba | 3012 | ibau | 30012 | ibai |

| four | uga | 4012 | ugau | 40012 | agai |

| five | ida | 5012 | idau | 50012 | idai |

| six | ela | 6012 | ulau | 60012 | ulai |

| seven | oica | 7012 | icau | 70012 | icai |

| eight | eza | 8012 | ezau | 80012 | ezai |

| nine | oka | 9012 | okau | 90012 | okai |

| ten | iapa | 120 i.e.(10x12) | apau | 10x12x12 | apai |

| eleven | uata | 11x12 | atau | 11x12x12 | atai |

You will noticed that 12 numbers over eleven have been shortened. For example the "regular" form for 20 would be auvau, but this is actually uvau.

Also the number 6, ela has been shortened. This would have been eula if everything was perfectly regular.

In the above table, 10 is actually, of course 12 : 90 is (9x12)+0 => 108 etc. etc.

The numbers in the above table combine, to express every number from 1 -> 1727 in one word. For example ;-

| 54312 | idaigauba |

| 50312 | idaiba |

| 64012 | ulaigau |

| 7212 | icauva |

| 612 | ela |

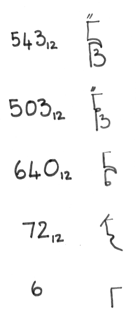

The above explains about the pronunciation of the numbers. But how are they written.

In fact the numbers are NEVER written out in full. See below for the characters corresponding to the five numbers above.

It can be seen that all the vowels are dropped and there is a horizontal line inserted in the top left of the character. The symbol for h is used for inserting zeroes (although never pronounced).

If you had a leading zero you would use the word jù which is usually placed before nouns and means "space/empty/zero/no". 007 would be jù jù oica (three words)

To deal with a telephone number, you would lump the numbers in threes (any leading zero by itself though) and outspeak the numbers. If you were left with a single digit (say 4) it would be pronounced agai. If you were to pronounce it uga, it would of course mean 004. Also you would probably add the particle dó at the end. This means "exactly" (or it can mean the speaker has finished outspeaking the number)

Ordinal numbers

To get an ordinal number you just attach n- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

| first | naja |

| second | nauva |

| third | naiba |

| fourth | nida |

| etc. | etc. |

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of nò plus the number.

These forms are adjectives 100% and are always written out in full.

Fractional numbers

To get an fractional number you just attach d- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

| a unit ? | daja |

| a half | dauva |

| a third | daiba |

| a quarter | dida |

| etc. | etc. |

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of ??? plus the number.

These are fully numbers. They are written in the same way as numbers, except the have a squiggle above them. The squiggle looks like an "8" on its side that hasn't fully closed.

..... Pronouns and what is meant by S, A and O

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In béu the word order is free).

timpa = to hit ... timpa is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb).

pás ò timpari = I hit him pà ós timpori = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person singular.

So far so good. And we see that English and béu behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example doika = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in béu we don't have *ós doikori but ò doikori (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is.

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument. For example òS flomporta = She has tripped

It is the convention to call the doer in a transitive clause the A argument. For example ósA timpori jene = He hit Jane

It is the convention to call the "done to" in a transitive clause the O argument. For example ò timpori jeneO = He hit Jane

The S was historically from the word "Subject" and the O historically from the word "Object", but it is best just to forget about that. In fact when I use the word "subject" I am talking about either the S argument or the A argument.

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

Below are two tables showing the two forms of the béu pronouns.

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

There could be another member it the above table. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves, a special particle tí is used.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

One other point ... béu has generally a pretty free word order. But in a sentence such as jene tí laudori (Jane washed herself) it would be pretty unusual to have the tí before jene

There is an emphatic pronouns based on the possessed form of bùa "body". The emphatic forms are given below ;-

| me myself | bapua | we ourselves | bayua |

| we ourselves | bawua | ||

| you yourself | bigua | you yourselves | bejua |

| him himself, her herself | bonua | them themselves | bunua |

| it itself | bisua | them themselves | bisua |

The above forms come just after the normal pronouns and the two words stand in apposition. If a pilana is applied to one, it must be applied to the other as well. For example ;-

pás bapuas ò timparu => I myself will hit her

..... 64 Adjectives

| good | bòi | bad | kéu |

| long | yàu | short | wái |

| high, tall | hái | low, short | ʔàu |

| happy, glad | ʔoime | sad, unhappy | heuno |

| white | ái | black | àu |

| young | sài | old (of a living thing) | gáu |

| clever, smart | jini | stupid, thick | tumu |

| near | nìa | far | múa |

| new | yaipe | old, former, previous | waufo |

| big | jutu | small | tiji |

| hot | fema | cold | pona |

| open | nava | close | mapa |

| simple, easy | baga | complex, difficult, hard | kaza |

| sharp | naike | blunt | maubo |

| wet | nuco | dry | mide |

| empty | fene | full | pomo |

| fast | saco | slow | gade |

| strong | yubu | weak | wiki |

| heavy | hobua | light | ʔekia |

| beautiful | hauʔe | ugly | ʔaiho |

| contiguous, touching | yotia | apart, separate | wejua |

| fat | somua | thin, skinny | genia |

| bright | selia | dull, dim | golua |

| thin | pilia | thick | fulua |

| east, dawn, sunrise | cúa | west, dusk, sundown | dìa |

| tight | taitu | slack, loose | jauji |

| neat | ilia | untidy | ulua |

| soft | fuje | hard | pito |

| wide/broad | juga | narrow | tisa |

| rough | gaʔu | smooth | sahi |

| deep | gubu | shallow | siki |

| right | sèu | wrong | gói |

In the above list, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | au | |||

| f | o | |||

| b | oi | |||

| g | i | |||

| d | ia | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ua | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | u | |||

| k | eu | |||

| p | e | |||

| t | ai | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

... Parts of speech and word order ... part 1

The main parts of speech in béu are nouns, adjectives and verbs (there are also particles but they are a mixed bag, it is hard to generalise about them). However we can generalise about nouns, adjectives and verbs. Nouns (N), adjectives (A) and verbs (V) are called "parts of speech". In this section we are going to talk about how a word can changed its part of speech. Sometimes a word can be a member of 2 or 3 different parts of speech without changing its form, sometimes a change of form is necessary ... typically an affix is added. For convenience I am going to introduce another type of word called geladi (G), this is the infinitive form of the verb. This is the "base form" of the verb and it resembles a noun in many respects(but not in everyway). In English the infinitive form is usually preceded by "to".

For example solbe means "to drink" and is a geladi (G). But more often you find this word in other forms. For example if you came across solbarin which means "I drank, so they say". I am counting the form solbarin as a verb (V), and the form solbe as a geladi. That is I am treating them as different parts of speech. This is just for convenience. I do not want to get into an argument about linguistic theories etc. etc. This is just to make things easy to discuss.

Let us start of with a single syllable adjective and see what "forms" single syllable adjective can take and what "parts of speech" these forms can belong to. Let us take the word gèu "green" ;-

Along the top of the above chart you can see N, A, V and G. These are different part of speech. The form under these 4 headings, shows the form géu takes when it is one of these 4 parts of speech. Now géu is fundamentally an adjective ... that is what that pentangle around the "A" means. In the above chart we can see that an unmodified géu can also function as a noun sometimes. When it acts as a noun it would mean "the/a green one". But how can we tell if géu is representing a noun or an adjective. Well we can tell by the position of gèu with respect to other elements in the clause.

gèu is an adjective if it comes immediately after the copula sàu. For example báu rì gèu => The/a man was green.

gèu is also an adjective if it comes immediately after a noun i.e. báu gèu dí => This green man *

In other positions géu represents a noun.

We can see that we can derive two verbs from géu. By affixing -du we get an intransitive verb meaning "to become green". And by affixing -ldu we get an transitive verb meaning "to make green". You can see that the V-forms and the G-forms are the same.

To make a "finite" verb, i.e. what I call V from the G form, it is always the same process. First you delete the final vowel, then you add a vowel that represents the subject, then you add, either r, n or s (depending if you want the indicative mood, the subjunctive nood or the imperative), then you add a vowel (or consonant + vowel) which is the tense/aspect marker followed by an optional evidential marker n, s or a. So we could get geudu + i + r + i +a => geudiria = "you became green, I saw it."

You can see that two nouns are made from géu. Well one does not change its form, I call this one "the substantive noun", i.e. "the green one". The other changes its form by taking an affix. I call this one "the qualitative noun", i.e. "greenness".

OK.

gèu is a qualitative noun if it comes immediately after the copula gaza i.e. ʔá pona => It is cold .....

ʔá pona paʔe => I am cold ... (O.K. we had to use a different adjective to demonstrate this one)

In other positions, if you want to express the qualitative noun, you must add the pilana -ma i.e. geuma => greenness

In all other positions gèu is a substantive noun i.e. it means "a/the green one" which will either have human or non-human reference, depending on context.

For gèu to be an verb, it needs to be modified i.e. geudu => to make green, to greenify **

nava is an adjective meaning "open" ... also a verb meaning "to open" ... or should that be "navau", with "to close" = mapai ??

(pás) tí gedari => I made mysef green

(pà) lari gèu => I became green

pà geudari => I became green ??? Is THIS my passive (not a proper passive), some sort of middle voice ??? what about LABILES ?

- By the way, if you want to qualify a noun with two adjectives, you must use a relative clause i.e. báu tà gèu té jutu => The/a big and green man

- By the way dú is a verb meaning "do"

gubu = deep, myigo = channel or canal,

gubuduri myigo = they deepened the canal

for the gamba the suffix du must be added.

gubudu = to deepen

All these derived verbs are transitive. That is they indicate the action is performed by one body on another body.

For the intransitive verbal meaning associated with these adjectives, the word selau (to become) must be used.

myigo gubu lori = the channel became deep (maybe by some sort of tidal activity) ... selau is one of the irregular verbs. Its r-form drops the initial se-

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

audu = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

auduri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences