Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb: Difference between revisions

| (329 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Welcome to <big> '''béu'''</big> | Welcome to <big> '''béu'''</big> | ||

== ..... Person/Tense/Evidence== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Also called the '''r'''-form or the indicative. | |||

.. | .. | ||

To make a verb in the indicative mood, you must first deleted the final vowel from the base form. Then add affixes that indicate "agent", "indicative mood", "tense", "evidentiality" and "perfectness". We will refer to these as slots 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively. All these affixes together are known as the verb tail. The "agent", "indicative mood", "tense" are mandatory ... however one tense, the aortist is a null morpheme. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... Seven Persons=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Slot 1 is for the agent | |||

.. | .. | ||

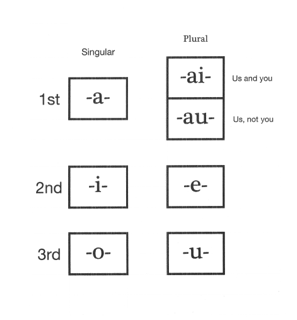

One of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer.. | |||

[[Image:TW_109.png]] | |||

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive. | |||

Some people might have difficulty remembering whether to use '''ai''' or '''au'''. The diagram below might help some ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_08.png]] ............... [[Image:SW_09.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

Mathematically it is as if ... '''ai''' = me + you ... and ... '''au''' = me + they ....... (sort of) | |||

The vowels of the first person plural inclusive pronoun '''magi''' are reflected in the infix -'''ai'''-. | |||

As are the vowels of the first person plural exclusive pronoun '''manu''' reflected in the infix -'''au'''-. | |||

.. | |||

Note that the '''ai''' form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function. | |||

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ... | |||

'''doika''' = to walk | |||

'''doikar''' = I walk | |||

'''doikair''' and '''doikaur''' = we walk | |||

'''doikir''' = you walk | |||

''' | '''doiker''' = you walk | ||

''' | '''doikor''' = he/she/it walks | ||

'''doikur''' = they walk | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The R-form=== | |||

.. | |||

One mood | |||

.. | .. | ||

Slot 2 is for the indicative mood marker. | |||

.. | .. | ||

At this point we must introduce a new sound and a new letter. | |||

[[Image:TW_355.png]] | |||

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in grammatical suffixes and it indicates the indicative mood. | |||

If you hear an "r" you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... Five Tenses=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Slot | Slot 3 is for tense markers. There are 5 tense markers in '''béu''' | ||

.. | .. | ||

1) '''*doikaro''' => '''doikar''' = I walk (habitually) | |||

This could be called "the open tense" ... timewise there are no limits to an action marked in this way. Also called "the timeless tense". A sort of habitual tense. Often used for generic statements. For example ... | |||

'''ngur jwadoi''' = "birds fly" | |||

Actually you can say this tense has an underlying '''o''' which appears again if there is an '''n''' or '''s''' in slot 4. | |||

2) '''doikaru''' = I will walk | |||

This is the future tense | |||

''' | 3) '''doikari''' = I walked | ||

''' | This is the past tense. This means that the action was done before today (by the way ... the '''béu''' day starts at 6 in the morning). | ||

''' | 4) '''doikare''' = I walked | ||

''' | This is the near-past tense. This means that the action was done earlier on today (a good memory aid is to remember that '''e''' is the same vowel as in the English word "day") | ||

''' | 5) '''doikara''' = I am walking | ||

This is the present tense ... it means that the action is ongoing at the time of speaking. | |||

.. | .. | ||

It can be seen that '''béu''' is more fine-grained, tense-wise than most of the world's languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/66 and http://wals.info/chapter/67 | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... Evidentials=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Two Evidentials | |||

.. | |||

Slot 4 can have one of the evidential markers '''a''', '''a''', '''n''', '''s''' or it can be empty. | |||

Actually the first '''a''' defines the subjects attitute rather than any evidentiality, however all 4 are usually just called evidential markers. | |||

.. | |||

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. However it is not mandatory to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In fact most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker. | |||

The markers are as follows ... | |||

1) -'''n''' | |||

= | For example ... '''doikorin''' = "I guess that he walked" ... That is the speaker worked it out from circumstances/clues observed. | ||

. | I will mention '''waron''' here. It means "I think so" and is nearly as common an answer as '''aiwa''' "yes" | ||

2) -'''s''' | |||

.. | For example ... '''doikoris''' = "They say he walked" ....... That is the speaker was told by some third party(ies) or overheard some third party(ies) talking. | ||

3) -'''a''' | |||

For example ... '''doikoria''' = "he walked, I saw him" ...... That is the speaker saw it with his own eyes. | |||

Note that the above evidential only co-occurs with the past tense and near-past tense. Actually when used with the near-past tense, '''*ea''' => '''ia''' so the distinction between "past" and "near-past" is lost for this evidential. | |||

Now there is a forth possibility for this slot ... and it is not actually an evidintial. Furthermore it has the same form as 3). | |||

''' | 4) -'''a''' | ||

For example ... '''doikorua''' = "he intends to walk" ... the agent in this case must be a sentient being of course. | |||

This evidential marker only co-occurs with the future tense. | |||

If the speaker doesn't know the evidential or deems it unimportant then this slot can be left empty. According to corpus studies in '''béu''', 60% - 70% of '''r'''-form have nothing in this slot. | |||

.. | |||

So the complete verb prefix system is ... | |||

[[Image:TW_980.png]] | |||

.. | |||

It can be seen that the '''béu''' evidentiality inventory is quite substantial compared to other languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/78 | |||

Also it appears that 4 or 5 categories being appended to the verb is typical of languages of the world. See ... http://wals.info/chapter/22 [If I have understood the chapter properly] | |||

.. | |||

=== ... For brevity=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

We have seen that in the verb tail, '''o''' is not pronounced if it comes final (the aortist tense). | |||

The reason for this is brevity of speech. | |||

For brevity of writng, every occurrence of '''o''' is not written (in the verb tail). For example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:TW_795.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ... Probability/Aspect/Negation== | |||

.. | .. | ||

We have already covered the 4 slots for "agent", '''r''', "tense" and "evidentiality" at the end of the verb. As well as the nuances given by these suffixes, there are particles which add further information to the basic verb. These are called (near-standers ?). These particles occur in three pre-verbal slots. | |||

The | The two particles in the first slot show probability. | ||

The seven particles in the second slot have to do with aspect in some way. Aspect can be tricky. | |||

In the third slot, only one particle : the negating particle '''bù'''. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Two probability particles === | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:SW_051.png]] | |||

.. | |||

'''lói''' = probably | |||

'''màs''' = possibly | |||

If nothing is in this slot, one assumes probability is 100% ... the option to challenge the underlying premise is never really considered. | |||

The probability distribution for '''lói''' centres around 85 %. | |||

The probability distribution for '''màs''' centres around 50 %. | |||

One can indicate a probability distribution centred around 15 % by using '''lói''' + '''bù'''. For example ... '''lói bù doikor''' = He/she probably doesn't walk. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... Two habituality particles === | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_052.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

Every verb can be considered to have a default probability distribution over time. | |||

[[Image:TW_984.png]] .... By the way, don't worry too much about the time scale in these sketched. | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''timpa''' and '''nko''' have very simple default probability shapes. But the typical (possible) probability distribution for '''kludau toili''' is more complicated. | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:SW_001.png]] | |||

Likewise the typical (possible) probability distribution for '''bunda tìa'''. | |||

We can group all verbs into 3 classes occording to their probability distribution over time. | |||

.. | 1) Punctual event ... '''timpa''' | ||

2) Steady state ....... '''nko''' | |||

3) Process ............ '''kludau toili''' or '''bunda tìa''' | |||

.. | Now every verb (actually "very situation" would be more acurate) have a range of typical probability distributions associated with them. However the '''béu''' aspect markers IMPOSE a typical probability distributions on any verb they touch. | ||

For example the particle '''awa''' imposes a probability distribution quite similar to '''kludau toili''' on ANY verb that it come in contact with. | |||

'''awa*''' gives a "habitual but irregular" (maybe best translated as "now and again" or "occasionally" or even "not usually") meaning to the verbal block. | |||

The particle '''bolbo*''' is similar to '''awa''' in a way. However it implies quite a bit of regularity. Maybe the regularity implied by ... | |||

. | [[Image:TW_985.png]] | ||

'''bolbo''' gives a "habitual and regular" (best translated as "normally" or "usually" or "regularly") meaning to the verbal block. | |||

.. | .. | ||

For | We saw earlier that of the five tenses. The first is a sort of habitual tense. For example ... | ||

'''doikar''' = I walk (with a sort of habitual meaning) ... OR ... I can walk (with a sort of potential meaning) | |||

''' | '''beucar''' = I am sick ... OR ... I am prone to sickness | ||

''' | So we have a sort of habitual meaning without needing to use either '''awa''' or '''bolbo'''. | ||

.. | However, if we wanted to restrict the habitualness to either the past or the future, '''awa''' or '''bolbo''' is needed. For example ... | ||

'''bolbo doikari''' = I used to walk (to school) | |||

''' | '''awa beucaru''' = I will be sick (when I start the chemotherapy) | ||

''' | '''awa''' or '''bolbo''' most often co-occur with tense (2) and tense (3). It is quite rare to have the right circumstances to use '''awa''' or '''bolbo''' with the other three tenses. | ||

.. | |||

'''*''' '''awa''' is possibly related to the verb '''awata''' which means "to wander". '''bolbo''' is possibly related to the verb '''bolbolo''' which means "to roll". [by the way '''boloi''' means "to turn over" (as in "to turn over a mat"). '''boloi''' also means revolution [ '''boloi peugan''' means "social revolution" or '''boloi tun''' means "political revolution" ... i.e. the French Revolution ]. '''gwò''' is possibly related to the verb '''gwói''' which means "to pass (by)". | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Three aspect particles === | |||

.. | .. | ||

Three aspect and a negating particle | |||

.. | |||

[ | [[Image:SW_053.png]] | ||

.. | .. | ||

With the three particles '''pín''', '''gwò''' and '''juku''', the fifth tense (present tense) never co-occurs. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Maybe the best way to approach '''pín''' and '''gwò''' is to consider process verb like "read the book" or "build a house" '''*''' | |||

Well you could say ... | |||

'''bù bundar tìa''' = "I don't build houses" ... which would put you out of the running. | |||

.. | But if you said '''bundar tìa''' ... and you were expected to build a house, one of the following might be applicable ... | ||

= | 1) '''hogi bù bundar tìa''' = I still haven't started to build the house | ||

2) '''pín bundar tìa''' = I am in the process of building a house | |||

3) '''gwò bundar tìa''' = I have built the house | |||

It is (2) and (3) we are interested in at the moment. | |||

Notice that '''bù bundara tìa''' = "I am not building a house" can be true when (2) is true. Remember that tense 5 refers to the EXACT time of speaking. | |||

[[Image:SW_056.png]] | |||

.. | |||

In English, it is a bit of a mouthful to say "I am in the process of building a house". So you can see that '''pín''' is a useful little particle when you want to be specific in this particular situation. However '''pín''' is the rarest out of '''pín''', '''gwò''' and '''juku'''. | |||

[Is '''pín''' also a preposition meaning during ... preceding a noun which is a period of time ?] | |||

.. | |||

Lets talk about '''gwò''' now. | |||

As we can see in (3), '''gwò''' is linked to the idea of completion. It is also linked to the idea of having done something at least once (to have "experienced" some action, in other words). For example ... | |||

'''gwò jàr glasgoh''' = "I've been to Glasgow" as opposed to '''jari glasgoh''' = I went to Glasgow | |||

As I said above, the present tense never co-occurs with '''pín''', '''gwò''' and '''juku'''. However the other 3 tenses are possible ... | |||

'''gwò jaru glasgoh''' = I will have been to Glasgow | |||

'''gwò jari glasgoh''' = I had been to Glasgow (with reference time sometime before today) | |||

= | '''gwò jare glasgoh''' = I had been to Glasgow (with reference time earlier today) | ||

.. | '''gwò''' could be called an experiential/resultative perfect. '''béu''' also has a resultative perfect expressed with the copula '''sàu''' and the suffix -'''in'''. | ||

The aspect distinctions available in '''béu''' are pretty fine-grained in some areas. Maybe if '''béu''' were to become a natlang, many of the fine-grain distinctions I have given it would fall by the wayside. | |||

.. | |||

''' | And now it's time to introduce '''juku'''. When '''gwò''' expresses the experiential idea (as it does above) '''juku''' expresses the non-experiential idea ... | ||

''' | '''juku jare glasgoh''' = I had never been to Glasgow (with reference time, earlier today) | ||

''' | '''juku jari glasgoh''' = I had never been to Glasgow (with reference time, before today) | ||

'''juku jaru glasgoh''' = I will never go to Glasgow (with reference time, before today) | |||

''' | '''juku''' like '''gwò''' is most often referenced to NOW. Hence ... | ||

''' | '''juku jàr glasgoh''' = I have never been to Glasgow. | ||

.. | |||

It is useful to compare the usage of '''juku''' against the usage of '''bù'''.This can best be explained by taking a punctual verb such as '''timpa'''. For example, suppose we were discussing "John hitting Paul yesterday afternoon". That particular instance of "hitting" can be negated with '''bù'''. However suppose it is wished to widen what is negated. Suppose that you want to say that there has been no instances of "John hitting Paul" (up until the present time of course), then you would use '''juku''' to negate the proposition. This is equivalent to "never" in English and I consider it an aspect particle. | |||

''' | '''jonos polo bù timpori''' = John did not hit Paul | ||

'''jonos polo juku timpori''' = John never hit Paul .... Notice that both '''timpori''' or '''timpore''' could be used. It depends upon what has been said before. | |||

'''bù''' is purely negation. It has no aspect to it. | |||

.. | [Note 1 ... The way '''juku''' negates '''gwò''' keeping the same aspect is similar to the way 没 méi (or 没有 méiyǒu) negates 了 le the perfect aspect particle, in Mandarin. 不 [bù] not being involved, just as '''bù''' isn't involved in '''béu'''. ] | ||

[Note 2 ... One little thing you should be aware off. I have equated '''juku''' with "never". Taking more strictly it should be equated with "have never". Let me expand on this ... | |||

a) "he has never worked" => '''juku kodor'''. | |||

b) "he doesn't work" or "he never works" => '''bù kodor''' .... in this one "never" in English is equivalent to the timeless tense plus the normal negator ... '''juku''' doesn't make an appearance ] | |||

.. | .. | ||

So to restate the '''béu''' aspect system ... | |||

'''juku kludar toili dè''' = I have never read that book ... not one word | |||

'''pín kludar toili dè''' = I have not completed that book (but I have read some of it) | |||

.. | '''gwò kludar toili dè''' = I have read that book .............. every word | ||

It is not really felicitous to say '''*bù kludar toili dè'''. However if you dropped the object, then '''bù kludar''' is acceptable. | |||

'''bù kludar''' => "I don't read" or "I never read" or even "I can't read" [This can be regarded as an event with a probability distribution over time, similar to '''nko'''. That is it is a sort of generic steady state event. For these sort of events '''bù''' is the normal negator] | |||

''' | "I don't intend to read this book" would be '''bù kludarua toili dè''' [And I think that exhausts everything I could want to do regarding "a/the book"] | ||

In a similar way constructions like "horses never fly" '''*kài fanfa juku ngur''' are frowned upon. "horses don't fly" '''kài fanfa bù ngur''' is considered more felicitous. | |||

.. | .. | ||

To | To restate the system yet again'''**''' ... | ||

''' | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| '''gwò kodor''' | |||

|align=left| he has worked | |||

|align=center| '''juku kodor''' | |||

|align=left| he has never worked | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gwò kodori''' | |||

|align=left| he had worked | |||

|align=center| '''juku kodori''' | |||

|align=left| he had never worked | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gwò kodore''' | |||

|align=left| he has worked (earlier today) | |||

|align=center| '''juku kodore''' | |||

|align=left| he hasn't worked (so far) today | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gwò kodoru''' | |||

|align=left| he will have worked | |||

|align=center| '''juku kodoru''' | |||

|align=left| he will never have worked | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

These three aspect particles also occur quite frequently in fronted adverb clauses. In these, '''pín''', '''gwò''' or '''juku''' are followed by an base form (plus any other bits and pieces relevant to the clause), then the main clause follows. English has similar. Here are three examples from English, illustrating the possible uses of these fronted adverb clauses ... | |||

1a) '''pín doika ... ''' : Walking dejectedly home, Peter noticed a sudden movement in the hedgerow. | |||

1b) '''tìa pà pín bunda''', I HAD TO LOOK AFTER TWO DAUGHTERS | |||

2a) '''gwò doika ... ''' : Having walked all the way home in the rain, Peter was ready for a hot bath and a cosy night in, in front of the TV. | |||

''' | 2b)'''gwò''' TO TAKE CITY, HE BURNT IT : urbem captem incendit | ||

3) '''juku jò ... ''' : Never having gone to Casablanca before, Peter soon got lost in a warren of small streets just north of the Bazaar. | |||

These type of fronted adverb clauses are considered good style. One comes across them quite often. Notice that the tense of the whole sentence is determined by the main clause. | |||

.. | |||

Note ... '''pín''' can also stand before a noun, a noun that represents a period of time. In which case it means "during". Or is can stand before a base verb, in which case it is equivalent to "while" or "during". Or it can appear in an active predicate, where it specifies a certain aspect type. | |||

.. | .. | ||

NOTE TO SELF ... does '''pín''' cover all occurrences of "while" and "when" in English ? | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''*''' I do not consider "read" and "build" in themselves to be process verbs, they are sort of open-ended affairs. But for "read the book" and "build a house" there is a definite completion time ... and completion state, implied. | |||

'''**''' You can't have too much of a good thing. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... Aspectual operators === | |||

.. | .. | ||

Two overlapping-action particles | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_054.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

I call '''ʔés''' and '''hogi''' "overlap words". | |||

Sometimes referred to as "aspectual operators" or "aspectual particles" in the Western Linguistic Tradition. | |||

Most languages have equivalents to these two particles ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

== | {|border=1 | ||

|align=center| English | |||

|align=center| already | |||

|align=center| still | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| German | |||

|align=center| schon | |||

|align=center| noch | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| French | |||

|align=center| déjà | |||

|align=center| encore | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| Mandarin | |||

|align=center| yîjing | |||

|- | |align=center| hái | ||

|- | |||

| | |align=center| Dutch | ||

| | |align=center| al | ||

| | |align=center| nog | ||

|- | |||

|align=center| Russian | |||

|align=center| uže | |||

|align=center| eščë | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| Serbo-Croatian | |||

|align=center| već | |||

|align=center| još | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| Finnish | |||

|align=center| jo | |||

|align=center| vielä | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| Swedish | |||

|align=center| redan | |||

|align=center| än(nu) | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| Indonesian | |||

|align=center| sudah | |||

|align=center| masih | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''béu''' | |||

|align=center| '''ʔés''' | |||

|align=center| '''hogi''' | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''hogi''' indicates ... | |||

1) An activity is ongoing. | |||

2) The activity must stop some time in the future, possibly quite soon. | |||

3) There is a certain expectation<sup>*</sup> that the activity should have stopped by now. | |||

.. | '''ʔés''' indicates ... | ||

1) An activity is ongoing. | |||

2) The activity was not ongoing some time in the past, possibly quite recently. | |||

3) | 3) There is a certain expectation<sup>*</sup> that the activity should not have started yet. | ||

.. | .. | ||

<sup>*</sup> Inevitably a connotation of "contrary to expectation" will develope to a certain degree. This is because if the situation was according to expectation often nothing would need be utterred. Hence '''hogi''' | |||

and '''ʔés''' are often found in contrary to expectation situation which in turn colours their meaning. | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_046.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

A very interesting thing about the overlap couplet is how they are negated cross-linguisticly. Either the particle can be negated or the verb can be negated. The first case I represent with a bar over the operator+verb. The second case with a bar over the verb only. | |||

Notice ... compared to the positive case, if the operator+verb is negated ... the line that represents onset/cessation of activity is moved to the other side of the dashed line representing "now". | |||

Notice ... compared to the positive case, if the verb is negated ... then the yellow place becomes white and the white space becomes yellow. | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:SW_007.png]] .... [[Image:TW_996.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

As you see by above ... by changing whether the negator act on the operator+verb or whether only on the verb give diametrically opposite meanings. | |||

Note that there are 4 possible negative cases to choose from and a language only needs 2. A language (to cover all negative cases) should be either "(a) (b) type" or "(c) (d) type" or " (a) (c) type" or "(b) (d) type" | |||

Cross linguistically there are interesting variations. All Slavic languages prefer verb negation, hence they are (c) (d) types. | |||

In German, only (a) and (c) are allowed in positive declarations. | |||

Nahuatl has negation of the operator so is (a) (b) type. | |||

English is a bit tricky ... it has suppletion and uses "not yet" for situation (c) and "no longer" for situation (d). Now in English "yet" means pretty much the same as "still". I believe "yet" was the original particle but "still" over time largely usurped it in the positive case. However the form "not yet" ... if taken at face value would seem to negate the operator. But it doesn't. Logically it would make more sense if we said "yet not" instead of "not yet" [i.e. we have situation (c) rather than (b)]. I am sure there is a perfectly good explanation for this reversal but unfortunately I do not know it ... anyway ... nothing to worry about too much. [ The form "not work yet" seems more logical in its word order ... how can "not" in "not yet work" have "work" under its scope but not "yet" ... but apparently that is the way it works ] | |||

In '''béu''', '''bù''' negates the verb and comes immediately before the verb. It has scope only over the verb, rather than the whole verb phrase. | |||

---- | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! hogi || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

| still || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | |||

|} ==> I am still working here | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! ʔés || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

| already || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | |||

|} ==> I already work here | |||

---- | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! hogi || bù || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

| still || not || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | |||

|} ==> I don't work here yet | |||

{| | {| | ||

|| | |- | ||

! ʔés || bù || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

| already || not || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | |||

|} ==> I no longer work here | |||

---- | |||

However although '''hogi bù''' and '''?é bù''' are possible, they are rarely encountered. Usually the terms '''jù dìa''' and '''uhoge''' are used. The provenance of these two terms is interesting ... | |||

'''jü''' means zero and is also used for negating nouns. '''dìa''' is a verb with quite a norrow meaning. It is what the sun does when it is revealing itself first thing in the morning. | |||

I guess '''jù dìa''' is an idiomatic expression. | |||

'''hò''' means "long" [not to be confused with '''hó''' the 13th '''pila?o'''). '''hoge''' means "longer". So '''uhoge''' means "no longer". | |||

So the actual system for these two negatives are ... | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! jù dìa || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

| "not yet" || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | |||

|} ==> I don't work here yet | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! uhoge || kod-a-r-a || dían | |||

|- | |||

|| | | "no longer" || work-{{small|1SG-IND-PRES}} || here | ||

|} ==> I no longer work here | |||

---- | |||

These operators are usually used to specify overlap with present time ... (I call the present time, NOW, in the diagrams). I would think this is true of every language (notice that the above examples the tense is always -'''a'''). However it is a trivial matter to reference the time of onset/cessation of activity to a different time ... you just change the tense. | |||

|| | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ... Verbal Moods== | |||

.. | .. | ||

When people speak they have different intentions. That is they are trying to achieve different things by speaking ... maybe they are trying to convey information, or wanting somebody to do something, or not to do something, or they are just expressing their feelings about something. All these are examples of what is called moods. Different languages have different methods of coding their moods. Also the various moods of a languages cover a different semantic range compared to other languages. | |||

There are 6 moods in '''béu'''. The prohibitive, indicative, optative, imperative, suggestive and interrogative ... 2 of these are represented by changes to the root and 4 by adding particles. | |||

Two verb forms ... the inflinitive and the conflative ... do not represent moods, but I present them here along with the moods. These both are represented by changes to the root. | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_189.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

How the different moods and forms interact are shown above. This will al be explained later. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... The base form=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

About 32% of multi syllable '''maŋga''' end in "a". | |||

About 16% of multi syllable '''maŋga''' end in "e", and the same for "o". | |||

''' | About 9% of multi syllable '''maŋga''' end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai". | ||

[[Image:TW_626.png]] | |||

Note that no '''maŋga''' end in "i", "u", "ia" and "ua" | |||

"i" is reserved for marking verb chains, which will be explained later. | |||

"u" is used for the imperative mood ... i.e. for commanding people. | |||

.. | "ia" is used for a past passive participle. For example ... | ||

'''yubako''' = to strengthen | |||

.. | '''yubakia''' = strengthened ... as in '''pazba dí r yubakia''' => "this table is strengthened" | ||

"ua" could be called the future passive participle I guess. For example ... | |||

'''ndi r yubakua''' => these ones must be strengthened | |||

To form a negative base form the word '''jù''' is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ... | |||

'''doika''' = to walk | |||

''' | '''jù doika''' = to not walk .... not to walk | ||

.. | |||

=== ... The imperative=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

You use the following forms for giving orders ... for giving commands. When you use the following forms you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action ... although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible. | |||

.. | .. | ||

For non-monosyllabic verbs ... | |||

The final vowel of the '''maŋga''' is deleted and replaced with '''u'''. | |||

'''doika''' = to walk | |||

'''doiku''' = walk ! | |||

.. | .. | ||

For monosyllabic verbs -'''hu''' is appended. | |||

'''gàu''' = "to do" | |||

'''gauhu''' = "do it" ... often '''só''' is added fot extra emphasis. | |||

'''só gauhu''' = do it ! | |||

One verb has an irregular form. | |||

'''jò''' = "to go" | |||

'''ojo''' = "go" ... actually a bit abrupt, probably expressing exasperation, veering towards "fuck off" ... '''jò''' itself can be used as a very polite form. | |||

.. | .. | ||

The imperative cab be directed at second person singular or second person plural. When addressing a group and issuing a command to the entire group you sort of let your eyes flick over the entire group. When addressing a group and issuing a command to one person you keep your eyes on this person when issuing the command ... maybe saying their name before the command ... probably preseded by '''só''' which is a vocative marker as well as being an emphatic particle. | |||

[ Note ... I think that in English, the infinitive usually has "to" in front of it, in order to distinguish it from the imperative. In '''béu''' too there is a need to distinguish between these two verb forms. However as the imperative occurs less often than the infinitive, I have decided to mark the imperative. ] | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The prohibitive=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

This is also called the negative imperative. Semantically it is the opposite of the imperative. It is formed by putting the particle '''kyà''' before '''maŋga'''. | |||

'''kyà doika''' = don't walk | |||

That is pretty much all there is to say about it. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The interrogative=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

The interrogative, also called a polar question. This is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no". | |||

.. | .. | ||

To turn a normal statement ( i.e. with the verb in its '''r'''-form) into a polar question the '''r''' is simply changed into '''?'''. | |||

And here is an example of it in action ... | |||

[[Image:SW_195.png]] ... '''lea r tiji''' = Lea's small [[Image:SW_190.png]] ... '''lea sòr tiji''' = Lea is small [[Image:SW_191.png]] ... '''lea so?o tiji''' = Is Lea small ? | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image: | Polar questions also exhibit a certain pitch contour ... the pitch rises towards the end of the utterance. There is a symbol to show this utterance pitch contour ... [[Image:SW_192.png]] | ||

However the '''béu''' question mark is never used when it is obvious that we have a question. But sometimes a single name, noun or adjective can constitute a question by itself. In these cases the special symbol is used. | |||

[[Image:SW_193.png]] ... Lea ? | |||

.. | .. | ||

The interrogative is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions. | |||

To answer a positive question you answer '''ʔaiwa''' "yes" or '''aiya''' "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language). | |||

Here is a positive question ... | |||

'''glá so?o hauʔe''' = Is the woman beautiful ? | |||

''' | To which you answer '''ʔaiwa''' "yes" or '''aiya''' "no". [Actually these two words have their own unique intonation pattern ... at least when said in isolation (see CH1 : Some interjections) ] | ||

.. | .. | ||

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. '''ʔaiwa''' and '''aiya''' are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ... | |||

'''glá bù so?o hauʔe''' = Isn't the woman beautiful ? | |||

If she is not beautiful, you should answer '''bù sòr'''<sup>*</sup>, if she is you can answer either '''sòr''' or '''soro''' or '''sòr hau?e''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

We have mentioned '''só''' already ... in the above section about '''seŋko'''. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick '''só''' in front of the word<sup>**</sup>. | |||

Another use for '''só''' is when hailing somebody .... '''só jono''' = Hey Johnny | |||

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange. | |||

'''só''' can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ... | |||

.. | |||

Statement ... '''bàus gláh nori alha''' = the man gave flowers to the woman | |||

Focused statement ... '''bàus só gláh nori alha''' = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers. | |||

.. | Unfocused question ... '''bàus gláh no?i alha''' = Did the man give flowers to the woman ? | ||

Focused statement ... '''bàus só gláh no?i alha''' = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ? | |||

.. | .. | ||

Any argument can be focused in this way. ['''béu''' also has a means of "fronting" to emphasize an element in a sentence. This is discussed elsewhere] | |||

.. | .. | ||

<sup>*</sup>Mmm ... maybe you could answer '''ʔaiwa''' here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous. | |||

<sup>**</sup>In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... The suggestive=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

We have come across '''kái''' before. In chapter 2.10 we saw that it was a question word meaning "what kind of". It normally follows a noun being an adjective. For example ... | |||

'''báu kái''' = what type of man ? | |||

''' | '''òn rò báu kái''' = what type of man is he ? | ||

'''òn rò deuta kái''' = what type of soldier is he ? | |||

'''dí kái''' = this is what type ? | |||

''' | But just as a normal adjective can be a copula complement, so can '''kái'''. | ||

'''òn rò kái''' = what type is he ? | |||

''' | '''dí r kái''' = this is what type ? | ||

''' | '''?ò r kái''' = what type of thing is it ? | ||

.. | However when you see '''kái''' utterance initial you know that it has a slightly different function : it is introducing the "soliciting opinion" mood. For example ... | ||

'''kái àn nyairu tìah jindi''' => "how about we go home now" => "let's go home now" | |||

.. | Actually '''kái àn''' is sometimes rendered simply '''àn'''. Maybe you come across the two alternatives an equal amount of times. | ||

''' | Is there any difference between the two forms ? Well ... yes. '''kái àn''' is used when the proposed venture is connected to leisure and pleasure. '''àn''' is used in more work-a-day situations. | ||

''' | Now ... as with the "optative", the "soliciting opinion" mood is usually orientated towards the future and uses '''maŋga'''. However their are circumstances where you solicit opinion about past events [for example a group of detectives on a crime scene discussing the possible steps taken by the perpetrator]. In these circumstances the '''r'''-form would be used preceded by the particle '''tà''' ... [see the table in the section above] | ||

The <u>main</u> thing about this mood is that the speaker is asking for feedback/advice/approval or disapproval. But it overlaps with the field "gently suggesting a course of action" somewhat. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... The conflative=== | |||

.. | |||

''' | Actually the verb itself is called an '''i'''-form verb. But a clause that has one or more '''i'''-form verbs is called a conflative clause. | ||

I will only touch on this subject here ... in Ch 10 there is a section that goes into this verb form in exhaustive detail. But one quick example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''jana jonos holdori nti flə sainyi uya''' => "yesterday John caught, cooked and ate three fish" | |||

.. | |||

yesterday = '''jana''' | |||

to catch = '''holda''' | |||

to cook = '''ntu''' | |||

to eat = '''flò''' | |||

three = '''uya''' | |||

''' | fish = '''sainyi''' | ||

.. | .. | ||

'''totai timpə+ri jw+ daun''' = the child was hit and died (instantly) [Note to self : how to say "the child was hit and died later"] | |||

'''totai''' = a/the child | |||

'''timpa''' = to hit | |||

'''jwòi''' = to undergo | |||

'''dàu''' = to die | |||

'''dàun''' = to kill | |||

'''jwòi dàun''' = to be killed | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | In a conflative clause, the first verb is conjugated as normal. However the remaining verbs are in their '''i'''-form. That is ... the final vowel of the '''manga''' is deleted and replaced with "i". If the verb is monosyllabic, the final vowel is replaced with a schwa. Semantically the'''i'''-form verbs follow the first verb. That is '''nti''' means '''ntu.ori''' and '''flə''' means '''flori'''. | ||

In conflative clauses, there can only be one subject but there can be more than one object. A conflative clause can consist of a mixture of H verbs and ɸ verbs. If the first verb is H then the subject is in its ergative form, otherwise it is in its base form. In the example given here, the three verbs have a definite time order, so the verb order is pretty much set. But we shall see in Ch 10 many examples where this is not the case. | |||

.. | |||

Note | Note ... in this example, all three verbs are intransitive and have the same object. So '''léu sainyi uya''' can not come between any of the verbs, but must come either before them all or after them all ... | ||

'''jana jonos sainyi uya holdori nti flə''' => "yesterday John caught, cooked and ate ''the'' three fish" | |||

.. | .. | ||

My motivation for having the conflative is to express meanings such as "through" or "into" by pure verbs ... i.e. "to go through", "to enter". | |||

''' | Also the '''béu''' verb tail can get pretty long so I didn't want it to be necessary to repeat it three or four times in quick succession. | ||

Conflative clauses are very often used to describe situations involving motion. But no actual restrictions on what verbs can enter into a conflative clause (of course the verbs plus other arguments must represent a coherent subset of reality. That is the overall clause must make sense semantically). | |||

.. | .. | ||

To say that one activity happens totally within the time of an other activity, we use the conflative plus the particle '''pín''' which we met earlier in this chapter. For example ... | |||

'''jonos lailore pín doiki''' = "John sang while walking earlier today" | |||

'''jonos lailore pín doiki tunheun''' = "John sang while walking to the civic centre earlier today" | |||

The whole constuctions (i.e. '''pín doiki''' and '''pín doiki tunheuh''') are equivalent adverbs. | |||

''' | An adverb meaning "the '''r'''-form (matrix verb) happened during the time of the '''pín''' + -'''i''' verb". | ||

.. | |||

=== ... The optative=== | |||

.. | |||

See Ch 4 : The particles '''àn''' and '''gò''' | |||

.. | |||

== ..... Negativity== | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''béu''' has three particles/prefixes for expressing negativity. | |||

Different particles for different parts of speech. Usually the particle is immediately to the left of the concept it modifies. | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:SW_145.png]] | |||

.. | |||

'''bù''' negates the live verb (i.e. the verb in its r-form). We have encountered '''bù''' already in the section "probability/aspect/negation". | |||

The verb in its u-form is negated by the particle '''kyà''' to the left of the '''maŋga'''. For example ... | |||

.. | |||

''' | '''sauhu bòi'''= be good | ||

However '''kyà sàu bòi''' = "don’t be good" instead of '''*bù sauhu bòi''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

The verb in its u-form can not be negated. | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''u'''- can connect to any adjective. | |||

'''?ár wèu u.ai''' = I want a nonwhite car (I want a car, any colour but white) | |||

''' | '''u'''- can on occasion be prefixed to nouns, the same as "non"- is used in English. However this construction is quite rare. | ||

''' | '''u'''- can connect to some verbs. The number of verbs it can connect to is limited ... about 20 or 30. Here are some examples ... | ||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''kunja''' | |||

|align=center| to fold | |||

|align=center| '''ukunja''' | |||

|align=center| to unfold | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''laiba''' | |||

|align=center| to cover | |||

|align=center| '''ulaiba''' | |||

|align=center| to uncover | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''tata''' | |||

|align=center| to tangle | |||

|align=center| '''utata''' | |||

|align=center| to untangle | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''fuŋga''' | |||

|align=center| to fasten, to lock | |||

|align=center| '''ufuŋga''' | |||

|align=center| to unfasten, to unlock | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''benda''' | |||

|align=center| to assemble, to put together | |||

|align=center| '''ubenda''' | |||

|align=center| to take apart, to disassemble | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''pauca''' | |||

|align=center| to stop up, to block | |||

|align=center| '''upauca''' | |||

|align=center| to unstop | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''senza''' | |||

|align=center| to weave | |||

|align=center| '''uzenza''' | |||

|align=center| to unravel | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''fiŋka''' | |||

|align=center| to put on clothes, to dress | |||

|align=center| '''ufiŋka''' | |||

|align=center| to undress | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

''' | '''jù''' negates nouns. In the next chapter we will encounter it in the section on numbers. It means "zero". | ||

''' | It also negates '''maŋga''' or dead verbs. | ||

It also negates clauses. For example ... | |||

'''jù àn ?ár jò''' = "not that I want to go" | |||

.. | .. | ||

Sometimes '''béu''' uses two of these three methods in the same sentence. I guess you could call this double negation. Double negation does NOT cancel, and it does NOT produce emphatic negation. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Here is an example of '''bù'''/'''jù''' double negation ... '''jenes bù mbor jù flò cokolata''' ... meaning "Jane lacks the willpower to resist chocolates". | |||

.. | .. | ||

And here is an example of '''bù'''.-'''u''' double negation ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

[[Image:SW_149.png]] ..................... [[Image:SW_148.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''mutu/umutu''' "important/unimportant" patterns with such antonym pairs as big/small ( '''jutu/tiji''' ) in that the two pole values together do not fill up the entire semantic space. | |||

.. | |||

Sometimes you have a choice, as to which negative to use. As in English, where "I don't have a house" can also be exressed as "I have no house". in '''béu''' you can say '''bù byár tìa''' or '''byár jù tìa'''. For both languages the latter form comes across as being more vivid, carries greater emotion [I am not 100% sure why this should be so]. | |||

.. | |||

== ..... Six useful verbs== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Six verbs of a kind | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|| '''bala''' | |||

|| to open | |||

|| '''kala''' | |||

|| to shut/close | |||

|- | |||

|| '''bana''' | |||

|| to let go, to release, to free ... | |||

|| '''kana''' | |||

|| to connect, to make fast, to join | |||

|- | |||

|| '''baza''' | |||

|| to empty | |||

|| '''kaza''' | |||

|| to fill | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

And we have six common adjectives derived from the above ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

{| border=1 | |||

|| '''balya''' | |||

|| open | |||

|| '''kalya''' | |||

|| shut/closed | |||

|- | |||

|| '''banya''' | |||

|| free, seperate | |||

|| '''kanya''' | |||

|| connected, joined | |||

|- | |||

|| '''baʒya''' | |||

|| empty | |||

|| '''kaʒya''' | |||

|| full | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|| '''balo''' | |||

|| an key | |||

|| '''kalo''' | |||

|| a (window)shutter/valve | |||

|- | |||

|| '''bano''' | |||

|| padding | |||

|| '''kano''' | |||

|| link/connector | |||

|- | |||

|| '''bazo''' | |||

|| a void/vucuum | |||

|| '''bano''' | |||

|| fill | |||

|} | |||

The '''o''' suffix implies something solid. "connection", "association" or "relationship" would be covered by the '''manga''' ... '''kana'''. | |||

'''bazda''' = desert ?? : '''kazda''' = ocean " '''kanda''' = an intersection ?? : '''balda''' = a gap/opening | |||

'''bano''' originally padding to separate a warriors leather armour from his tunic. | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ..... Valency== | |||

.. | .. | ||

In every language a particular verb can be associated with a number of nouns (we usually called these nouns arguments of the verb). For example .... | |||

{| | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | ! jono-s || jene-h || slaigau || haun-o-r-a || eŋglaba-tu | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | John-{{small|ERG}} || Jane-{{small|DAT}}|| calculus || teach-{{small|3SG-IND-PRES}} || English-{{small|INST}} | ||

|} ==> | |} ==> John is teaching calculus to Jane in English | ||

In the above example "teach" is associated with 4 nouns. | |||

Now things can get a bit confusing here. Some people hold that it is easy to distinguish between "core arguments" which are essential and "peripheral arguments" which simply add more information. But this is questionable. The consensus w.r.t. English seems to be that if an argument requires a preposition, then it is a "peripheral arguments", if no preposition required then it is a "core argument". A simple to implement system at the least. | |||

.. | In the above example "English" can be dismissed as a peripheral argument because of "using". But what about "Jane". In the above example Jane's roll in the clause is defined by the prefix "to". But what if "John is teaching calculus to Jane in English" is re-arranged as "John is teaching Jane calculus in English"? Here you have three nouns not qualified by a prefix. In English "teach" is sometimes called a ditransitive verb (a verb that can take three essential (unmarked) arguments). | ||

It is | In '''beu''' no verbs are considered ditransitive ... Jane will always be marked by the dative suffix. Now you might argue that every instance of teaching involves "somebody getting taught" ... well this is true, but it is also true that every instance of teaching involves some language being used. At the end of the day ... the English verb "teach" means ''exactly'' the same as its '''béu''' equivalent ( '''haun''' ). It is just that there are two different conventions for expounding an action (verb) in two different linguistic traditions. The '''béu''' linguistic tradition is the simplest :-) | ||

The '''béu''' linguistic tradition divides all verbs in into two types .... H (transitive) and Ø (intransitive). In dictionaries all verbs are marked by the simbol H or Ø. H means a transitive verb ( called a "dash verb" ) and Ø means an intransitive verb ( called a "stroke verb" ). The rule is ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

A verb is H if it is ever associated with a noun that has the ergative marker "-'''s'''". | |||

A verb is Ø if it is never associated with a noun that has the ergative marker "-'''s'''". | |||

.. | .. | ||

Now I will introduce the S A O convention which was devised by RMW Dixon. This convention is a useful way to refer to the arguments of transitive and intransitive verbs. The one argument of the intransitive verb is called the S argument. The argument of the transitive verb in which the success of the action most depends is referred to as the A argument. The argument of of the transitive verb is most affected by the action is called the O argument. | |||

O was probably chosen from "object", A from "agent" and S from "subject" ( I find this useful to keep in mind as a memory aid). However O does not "mean" object and A does not mean agent and S does not mean subject. I (and many other linguists) use the word subject to refer to either A or S. Easier to talk about "subject" that to talk about "A or S" all the time. | |||

[ In the '''béu''' linguistic tradition, the A argument is "the '''sadu''' noun", the O argument is the "the dash noun" and the S argument is the "the stroke noun".] | |||

.. | .. | ||

Now in English certain verbs appear to be Ø in some situations and H in others. These are called ambitransitive verbs. | |||

.. | .. | ||

1) The old woman knitted a sweater | |||

2) The old woman knitted | |||

"knit" is regarded as a "A=S ambitransitive". In (1) "old woman" is A ... in (2) "old woman" is S ... [ (2) is partially the reality described by (1) ] | |||

.. | |||

3) The old woman opened the door | |||

4) The door opened | |||

"open" is regarded as a "O=S ambitransitive". In (3) "the door" is O ... in (2) "the door" is S ... [ (4) is not inconsistant'''*''' to being partially the reality described by (3) ] | |||

.. | .. | ||

In '''béu''', there are no "ambitransitives. "knit" is considered H but with the O argument being dropped when it is unimportant or unknown. Similarly "open" is also considered H but with the A argument dropped'''**''' when it is unimportant or unknown. | |||

'''bala''' "to open" is always H in '''béu'''. In English, "open" is sometimes transitive and sometimes intransitive. | |||

Take '''pintu baləri***''' "the door opened". In English the proper analysis is "door" = "S argument". Well it is subject because it comes before the verb, and as it is the only argument it must be S. | |||

In '''béu''' the proper analysis is "door" = "O argument". We know '''bala''' "to open" is H becuse on occasion it can occur with A arguments. However in this case the only noun ('''pintu''') is not marked for the ergative hence it must be the "O argument". | |||

''' | '''pintu baləri''' could also be translated as "the door was opened". | ||

.. | |||

'''*'''(4) leave open the question whether human action brought about the action or it was due to some other cause. This question could be answered by rewriting (4) as either "The door was opened" or "The door opened by itself". | |||

''' | '''**'''Actually it would be possble to drop A arguments in English if the imperative was not the base verb. For example in English "knit a jersey" is a command ... but if English ... say ... suffixed "ugu" for the imperative, then the command would be "knitugu a jersey". That would allow "knit a jersey" to be interpreted as "jersey being knitted". | ||

'''***'''We haven't come across the schwa before the "r" before. This will be explained very soon. | |||

.. | .. | ||

So in '''béu''' …. each verb is either H or Ø … no ambitransitives or ditransitives. | |||

Also “the passive” is not talked about … rather it is just considered a particular case of “dropping”. And actually “dropping” is not considered a bit deal … just an very obvious thing to do. | |||

.. | |||

''' | Now one problem with dropping arguments is that the subject (S or A) must be represented in slot "1" of the indicative verb. How should we know what to put in here ( see Ch3.1.2.1 ). One solution could be to use the 3 person plural suffix -'''u'''- ... chances are that it is a 3rd person agent and the plural is more generic than the singular. This is what Russian does to make a sort of a passive. Another solution would be to use a vowel not already appropriated for pronoun agreement. This is what '''béu''' does. The schwa is inserted in the slot just before the "r". | ||

Everything collapses in ... to the schwa ... an impersonal schwa. | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:TW_664.png]] | |||

"the door opened" = "the door was opened" = '''pintu baləri''' (Actually I do not think the schwa symbol is visually distinct enough ... from now on I will use a cross) => '''pintu bal+ri''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

Here are some examples of this construction [ I will call it the impersonal construction from now on ] | |||

'''beuba bl+r dían''' = "The language of '''béu''' is spoken here" | |||

''' | '''pí gaudoheu dè_blanyo g+r''' = "In this factory telephones are made" | ||

''' | '''toilia bù ost+r pí duka dí''' = "Books are not sold in this shop" | ||

'''pintu by+r bala''' = '''pintu r balwa''' = the door has to be opened | |||

'''pintu mb+r bala''' = the door can be opened ........... [ to understand this example and the one above it ... see Ch 4.7 ] | |||

'''hala dè nyal+ryə''' = that rock is eroded .......... '''nyale''' = to erode, to wear | |||

.. | |||

Note ... the schwa can not support any tone. And as it is only used in the grammer and not in any base words as such it was not introduced in Chapter 1 (as '''r''' was not). The schwa is represented in fact by a cross in the '''béu''' writing system ... | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:TW_909.png]] | |||

Note ... Some '''béu''' speakers pronounce "schwa" + "syllable final rhotic" as "ø" or "ør". These people also tend to give "ø" the proper tone. However the majority pronoun a schwa followed by a rhotic appoximant with neutral tone. | |||

.. | |||

Now "door" is a man-made object and probably it exists in a place with many people around. So it is reasonable to expect there to be ''human volition'' involved when it opens. But what about when we get out into nature. When we see a river freezing. There is no agent to be seen behind this "freezing" ... it just happens. For this reason the verb "to freeze" '''doska''' is Ø. | |||

But now we have become clever ... we hold dominion over nature. Hence we need to derive a word for freeze that is H. And that deriration is arrived at by appending -'''n'''. | |||

Hence ... | |||

'''doska''' = to freeze | |||

'''moze doskori''' = the water froze | |||

'''moze doskanaru''' = I will freeze the water | |||

.. | |||

Actually any Ø can take this suffix and become H. Here are a few more examples ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

{| border=1 | {| border=1 | ||

| | || '''ngeu''' | ||

| | || to fly | ||

|| '''ngeun''' | |||

|| to throw | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''jó''' | ||

| | || to go | ||

|| '''jón''' | |||

|| to send | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''tè''' | ||

| | || to come | ||

|| '''tèn''' | |||

|| to summon | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''bái''' | ||

| | || to rise | ||

|| '''báin''' | |||

|| to raise | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''kàu''' | ||

| | || to descend | ||

|| '''kàun''' | |||

|| to lower | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''dàu''' | ||

| | || to die | ||

|| '''dàun''' | |||

|| to kill | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''slài''' | ||

| | || to change | ||

|| '''slàin''' | |||

|| to change | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | || '''diadia''' | ||

| | || to happen | ||

| | || '''diadian''' | ||

|| to cause | |||

| | |||

|} | |} | ||

.. | .. | ||

And here are a few more examples .... | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoime''' | |||

|align=center| to be happy, happyness | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimor''' | |||

|align=center| he is happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimen''' | |||

|align=center| to make happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimin''' | |||

|align=center| pleasant | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''heuno''' | |||

|align=center| to be sad/sadness | |||

|align=center| '''heunor''' | |||

|align=center| she's sad | |||

|align=center| '''heunon''' | |||

|align=center| to make sad | |||

|align=center| '''heunin''' | |||

|align=center| depressing | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''taude''' | |||

|align=center| to be annoyed | |||

|align=center| '''taudor''' | |||

|align=center| he is annoyed | |||

|align=center| '''tauden''' | |||

|align=center| to annoy | |||

|align=center| '''taudin''' | |||

|align=center| annoying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''swú''' | |||

|align=center| to be scared, fear | |||

|align=center| '''swor''' | |||

|align=center| she is afraid | |||

|align=center| '''swún''' | |||

|align=center| to scare | |||

|align=center| '''swu.in''' | |||

|align=center| frightening, scary | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''centa''' | |||

|align=center| to be angry, anger | |||

|align=center| '''centor''' | |||

|align=center| he is angry | |||

|align=center| '''centan''' | |||

|align=center| to make angry | |||

|align=center| '''centin''' | |||

|align=center| really annoying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''yode''' | |||

|align=center| to be horny, lust | |||

|align=center| '''yodor''' | |||

|align=center| she is horny | |||

|align=center| '''yoden''' | |||

|align=center| to make horny | |||

|align=center| '''yodin''' | |||

|align=center| sexy, hot | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gái''' | |||

|align=center| to ache, pain | |||

|align=center| '''gayor''' | |||

|align=center| he hurts | |||

|align=center| '''gáin''' | |||

|align=center| to hurt (something) | |||

|align=center| '''gai.iin''' | |||

|align=center| painful | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gwibe''' | |||

|align=center| to be ashamed/shame/shyness | |||

|align=center| '''gwibor''' | |||

|align=center| she is ashamed/shy | |||

|align=center| '''gwiben''' | |||

|align=center| to embarrass | |||

|align=center| '''gwibin''' | |||

|align=center| embarrassing | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''doimoi''' | |||

|align=center| to be anxious, anxiety | |||

|align=center| '''doimor''' | |||

|align=center| he is anxious | |||

|align=center| '''doimoin''' | |||

|align=center| to cause anxiety, to make anxious | |||

|align=center| '''doimin''' | |||

|align=center| worrying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔica''' | |||

|align=center| to be jealous, jealousy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔicor''' | |||

|align=center| she is jealous | |||

|align=center| '''ʔican''' | |||

|align=center| to make jealous | |||

|align=center| '''ʔicin''' | |||

|align=center| causing jealousy | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | '''jài ?oime''' is an adjective meaning happy by nature. | ||

Six H can also take -'''n''' as well. They are ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

{| border=1 | |||

|| '''flò''' | |||

|| to eat | |||

|| '''flòn''' | |||

|| to feed, feeding | |||

|- | |||

|| '''heca''' | |||

|| to see | |||

|| '''hecan''' | |||

|| to show, showing | |||

|- | |||

|| '''háu''' | |||

|| to learn | |||

|| '''háun''' | |||

|| to teach, tuition | |||

|- | |||

|| '''nko''' | |||

|| to know | |||

|| '''nkon''' | |||

|| to inform, informing | |||

|- | |||

|| '''pòi''' | |||

|| to enter, to join | |||

|| '''pòin''' | |||

|| to put in, insertion | |||

|- | |||

|| '''féu''' | |||

|| to exit, to leave | |||

|| '''féun''' | |||

|| to take out, extraction | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

.. | In English, all the above except the last would be considered ditransitive verbs. "to take out" would not be considered ditransitive because one argument would be marked by the preposition "from". In '''béu''' they are all still H although they have undoubtedly one extra noun compared to their non-derived counter parts. Remember H and Ø were defined as ... | ||

A verb is H if it is ever associated with a noun that has the ergative marker "-'''s'''". | |||

A verb is Ø if it is never associated with a noun that has the ergative marker "-'''s'''". | |||

(Note : '''fyá''' "to tell" means basically the same as '''nkon''' but is less formal. Also '''gàu''' means basically the same as '''diadian''' but is less formal. ) | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | We have discussed '''bala''' and '''doska''' so far. The first is considered basically H and the second one basically Ø. There is a third type of verb ... for this type it is hard to say if it is more basic as Ø or more basic as H. So these verbs have <u>two</u> basic forms. For example ... | ||

.. | |||

'''cwamo hulkori''' = the bridge broke | |||

''' | '''deutais cwamo helkuri''' = the soldiers broke the bridge | ||

.. | .. | ||

Actually for the first example .. the chances are that the breakage was due to wear and tear caused by human activity. But the important thing is that it is non-volitional. Also there might have been no humans around when the bridge actually did break. So we can talk about the bridge breaking by itself ... as if by an act of nature. And another example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | '''jono wiltore''' = John woke up (earlier today) | ||

''' | '''jenes jone woltore ''' = Jane woke up John (earlier today) | ||

.. | .. | ||

There are about 40 of these pairs. If the Ø has '''u''' the H will have '''e''' ... if the Ø has '''i''' the H will have '''o'''. | |||

So lets summarize these three typre of verb ... | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:TW_825.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

---- | |||

So to wrap it all up about verbs and arguments ... | |||

No verbs are ambitrasitive. They are either Ø or H. However it is easy to drop the A or the O argument from a H clause if either of them is considered trivial or is unknown. | |||

.. | Now in '''béu''' any H can be given a Ø meaning ( grammatically the structure is still H ) by making the the O argument '''tái''' ... meaning himself, herself, yourself etc. etc. However only animate A arguments do this. Hence ... | ||

''' | '''bàus tái timpori''' = the man hit himself ................. acceptable | ||

'''*pintus tái balori''' = the door opened itself ...... unacceptable | |||

In English there are two ways to report on a door opening without mentioning any agent ... "the door opened" and "the door was opened" | |||

''' | In '''béu''' only one ... '''pintu bal+ri''' ... which is just a H clause with the A argument dropped. Comparable to how "the old woman knitted"(as this would appear in '''béu''' of course) is a H clause with the O argument dropped. | ||

.. | |||

''' | In '''béu''' you can make a "passive participle" by suffixing -'''ia'''. | ||

''' | If you come across something broken and you know it was broken by human volition ... you would call it '''helkia'''. | ||

''' | If you come across something broken and you did not know how it was broken ... you would call it '''hulkia'''. | ||

If you come across something frozen you would call it '''doskia'''. There is no such word as '''*doskania'''. | |||

.. | .. | ||

In '''béu''' you can make the "general obligation participle" by suffixing -'''ua'''. | |||

.. | If you come across something that has to be broken ... you could refer to it as '''helkua'''. | ||

If you come across something that had to be frozen ... you could refer to it as '''doskanua'''. | |||

There is no such words as '''*doskua''' or '''*hulkua''' | |||

.. | |||

The | The above method of presenting a verb like '''bala''' hints at human volition. To get rid of this connotation (to suggest that the event happened naturely) we must use '''tezau''' "to become" plus an adjective. This is demonstrated below ... | ||

Consider '''geuko''' = "to turn something green" ... H ... derived from '''gèu''' "green" | |||

1) '''báu tezori gèu''' = The man became green .. ........................ ''natural'' | |||

2) '''báu geuk+ri''' = The man was made green .................... ''human volition'' | |||

3) '''báus tái geukori''' = The man made himself green ......... ''human volition'' | |||

.. | |||

Now consider '''bala''' = "to open" ... H | |||

1) '''pintu tezori balya''' = the door became opened = the door opened .......... ''natural'' ................ [ here the agent could be anything ... the wind ... or even some fairy '''cái''' ... use your imagination ] | |||

2) '''pintu bal+ri''' = the door was opened ............................................... ''human volition'' .... [ this one implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant and the action deliberate ] | |||

Note ... there is no (3) here as a door is non-human. | |||

.. | |||

In either of the (1)'s '''wistia''' "deliberately/carefully" or '''wistua''' "accidently/carelessly" can be added after'''*''' '''tezori'''. This automatically makes Agent => Human | |||

.. | The same for the (2)'s, but the incidence of '''wistua''' should greatly excede the incidence of '''wistia''' as "intention" is the default for this construction. | ||

With (3) the connotation of intent is so strong that '''wistia'''/ '''wistua''' could be considered a bit infelicitous ... not impossible but indicative of an unusual situation. | |||

'''*''' or '''wistiwe''' or '''wistuwe''' if not immediately after the verb. [by the way ... '''wisto''' = "mind/brain" by the way] | |||

.. | .. | ||

.. | |||

PUT ANOTHER WAY ... | |||

There are many actions that are kind of fluid as to the number of participants involved. When languages code an action they take into account whether the action is normally'''*''' involves a single paricipant or two participants [ three participants is also possible but that is another story ]. And then the relevant language will add extra stuff (an extra word … bit of word … something like that) when this action involves more or less participants than suggested by the basic word coding this action. | |||

Two examples from French. | |||

The action of boiling is deemed => single paricipant => bouillir | |||

When two participants, we add the word faire => faire bouillir | |||

The action of breaking is deemed => double paricipant => casser | |||

When only a single participant, we add the word se => se casser | |||

Certain languages deem certain actions pretty evenly split between single-participant manifestations and double-participant manifestations. In these cases, it can be impossible to determine what is the basic form of the verb. | |||

An example from Swahili. | |||

== | cham-k-a = to boil as the soup over the open fire boils | ||

cham-sh-a = to boil as your mother boils the water for a cup of tea | |||

Further examples, Japanese this time. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|| 生きる | |||

|| ikiru | |||

|| to live | |||

|: | |||

|| 活かす | |||

|| ikasu | |||

|| to revive | |||

|- | |||

|| 逃げる | |||

|| nigeru | |||

|| to escape | |||

|: | |||

|| 逃がす | |||

|| nigasu | |||

|| to set free | |||

|- | |||

|| 揺れる | |||

|| yureru | |||

|| to sway | |||

|: | |||

|| 揺らす | |||

|| yurasu | |||

|| to shake | |||

|} | |||

Japanese has a many verbs pairs of this sort. | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''*''' The choice can be culturally determined in some circumstances. Imagine a community in which each grown male visits the barber to get shaved every morning versus a community in which shaving is a private affair. The language of the former will inevitably pattern "shave" as transitive, anf the latter will inevitably pattern "shave" as intransitive. | |||

''' | |||

The | |||

The | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ..... To undergo== | |||

.. | .. | ||

We have seen the subjectless verb form above where the vowel before the '''r''' becomes a schwa.`However there is another way to drop a subject ... by using the verb '''jwòi''' "to undergo" followed by the base form. Of these two ways of dropping the subject, the former is overwhelmingly preferred. However for forming present participles and infinitives, the second method is necessary. | |||

''' | '''timp+ra pà''' = I am being hit : '''jwola timpa''' = being hit : '''jwòi timpa''' = to be hit | ||

[Note to self .... sort out the below ... and also all the RUBBISH PARTICIPLE stuff I have] | |||

''' | '''hecari jono katala lazde''' = I saw John cutting the grass ....................... '''katala lazde''' is a '''saidau kaza''' ..... '''katala''' is a '''saidau baga''' | ||

''' | '''hecari lazde jwola kata''' = I saw the grass being cut ............................. '''jwola kata''' is a '''saidau kaza''' | ||

''' | '''hecari lazde jwola kata hí jono''' = I saw the grass being cut by John .... '''jwola kata hí jono''' is a '''saidau kaza''' | ||

''' | Note ... although the '''là''' suffix is probably connected to the second '''pila?o''' it should be recognized as a separate siffix here. If it was the '''pila?o''' we would have ... '''bwari lazde là jwòi kata''' | ||

''' | '''hecari lazde kataya''' = I saw the grass that has been cut | ||

'''hecari lazde katawa''' = I saw grass that must be cut = I saw that the grass must be cut | |||

''' | '''lazde katawa hecari''' = I saw the grass that must be cut | ||

'''hecari lazde nài r katawa''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ..... The copula== | |||

.. | .. | ||

The three'''*''' components of a copular clause usually have a strict order'''***''' ... "copular subject" => "copula" => "copula complement". For example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... | {| | ||

|- | |||

| "copular subject" ||align=center| "copula" || "copula complement" | |||

|- | |||

! align=center| jono ||align=center| r || koduʒi | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| John ||align=center| is ||align=center| diligent | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| - ||align=center| - ||align=center| - | |||

|- | |||

! align=center| jono ||align=center| r || moltai | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| John ||align=center| is ||align=center| doctor | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

The copula's base form is '''sàu'''. You will see that it is listed among the 37 short verbs. However it patterns differently from the other 36. And indeed it patterns differently from all other verbs. Below are the '''r'''-forms of '''sàu''' ... | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:TW_969.png]] | |||

.. | .. | ||

The copula form rule ... "When the copular subject noun (or noun phrase) is overtly stated, use the short form. At all other times, use the long form" | |||

.. | .. | ||

In | The short form is used when the copular subject noun (or noun phrase) is overtly stated. In other situations the full form is used. For example when the copular subject is a pronoun'''**''', the long form must be used. | ||

You can see in the above chart that the short form of the aortist tense has two forms. '''ró''' is used in two situations ... | |||

1) If the copula subject ends in a consonant. For example .... | |||

'''sòs rò hau?e''' = the snow is beautiful | |||

2) If an evidential is tagged on. For example ... | |||

'''tìa ròn hau?e''' = the house is beautiful (I guess) | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''r''' by itself is used in all other situations.it is a clitic attached the the last vowel of the copula subject. However it is always written as a separate word. For example .... | |||

'''tomo r tumu''' = Thomas is stupid | |||

It takes the tone of the copula subject. | |||

.. | |||

The aortist form is the form corresponding to "am", "are" ans is in English. The present tense is "marked" (i.e. the unusual case that carries extra eaning). For example ... | |||

.. | |||

'''sòs rò hau?e''' = snow is beatiful ….. a timeless truth | |||

'''sòs rà hau?e''' = the snow is beatiful (for now) ... maybe the speakers are contemplating the snow melting and the consequent slush | |||

.. | |||

And another example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | '''jono r bòi''' = John is good (it is his nature) | ||

'''jono rà bòi''' = John is being good ... maybe to impress somebody who is visiting. | |||

Note ... to say '''jono rà bòi''' invalidates '''jono r bòi''' to a certain extent. | |||

.. | |||

''' | Because there is a strict word order, definiteness can not be expressed as it usually is with other verbs (S, O, A, dative ... left of verb if definite, right of verb if not). However the particles '''èn''' and '''ín''' can be drafted for this purpose. | ||

[Note to self : should every '''pila?o''' defined argument act thus ... what about other arguments ? ] | |||

It is only the '''r'''-form of the copula which is irregular. All other forms are perfectly normal. For example ... | |||

'''sauhu bòi''' = be good ................................................................. '''u'''-form | |||

.. | '''kodor sə kludado''' = he works as a clark .................................... '''i'''-form | ||

'''kodi sòr kludado''' = he/she works as a clark …........................… '''i'''-form .............. Actually, I think this way is better (change the rest of the website ?) | |||

.. | .. | ||

There is also the change of state copula, '''tezau'''. While '''tezau''' < '''té''' + '''sàu''', I would not call it a calque on English "become", rather the deep semantic process that formed "become" in English, worked also in '''béu'''. | |||

There is strict word order with this copula as well ... | |||

.. | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

| "copular subject" ||align=center| "copula" || "copula complement" | |||

|- | |||

! align=center| jono ||align=center| tezori || koduʒi | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| John ||align=center| became ||align=center| diligent | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| - ||align=center| - ||align=center| - | |||

|- | |||

! align=center| jono ||align=center| tezori || moltai | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| John ||align=center| became ||align=center| doctor | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

As you can see there is no erosion here. | |||