Béu : Discarded Stuff: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=== ... Two quotative verbs=== | |||

.. | |||

'''béu''' has two quotative verbs ... '''swé''' and '''aika'''. What I mean by the term "quotative verb"is a verb which must'''*''' be accompanied by a <u>s</u>tring <u>o</u>f <u>d</u>irect <u>s</u>peach ["sods" from now on] | |||

'''swé''' = "say" and '''aika''' = ask .... ( that is to ask for information, to request something (to ask for) has a completely different root ... namely '''tama''' ) | |||

I guess it is intransitive because the speaker never takes the ergative ending "'''s'''". The spoken to (if mentioned) takes the dative ending "'''n'''". | |||

[Some people would like to argue as to whether "sods" = an object or whether "sods" = a complement clause. I think this is not worth arguing about. It is similar to arguing about how many angels can stand on the end of a needle. ] | |||

There is an ordering restrictions for a clause formed around a quotative verb ... the "sods" must appear adjacent to '''swé''' or '''aika'''. It doesn't matter which comes first but they must be adjacent ... normally both elements are pronounced in the same intonation contour. A second restriction is that there must be a pause at the other end of the "sods" ... the opposite end from the quotative verb. For example ... | |||

John said "Ai ... go away" => '''jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo''' where '''aiʔdo''' is an interjection expressing frustration and '''ojo''' is quite a rough way to say "go away". | |||

This can also be expressed as '''aiʔdo ... ojo swori jono''' or '''jono ... aiʔdo ... ojo swori''' or even '''swori aiʔdo ... ojo ... jono'''. The first two patterns are the most common followed by the third pattern and the fourth a distant last. Notice that the "sods" that I chose for demonstration purposes entails an internal pause. | |||

If we introduced a dative element ... | |||

John said to Jane "Ai ... go away" => '''jono jenen swori aiʔdo ... ojo''' | |||

The above would be the most common ordering of constituents ... but again quite a bit of freedom with respect to word ordering. | |||

The "sods" can be quite lengthy ... 2 or 3 or 4 clauses and follows as near as possible the speach pattern of the original speaker. | |||

The '''béu''' orthography is a bit quirky when it comes to quotative verbs. In CH 1.8 we briefly mentioned the '''deupa'''. These are actually used to bracket any "sods". Also it is common to drop the actual quotative verb. (well after the time setting of the speach act(s) are revealed anyway). For example ... | |||

[[Image:TW_746.png]] | |||

The first one is graphically '''jono''' [ '''aiʔdo ... ojo''' ] ... (for an explanation of the graffic form of the interjection '''aiʔdo''', look back to CH 1.2) | |||

The second one is graphically '''jono''' [ '''bàu nái''' ] | |||

These would be read as '''jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo''' and '''jono aikori bàu nái''' (John asked "which man") | |||

But how do we know that '''swé''' should be associated with one and '''aika''' to the other ? Simple ... if you have a question word within the '''deupa''' then you know you should pronounce '''aika''' ... if not you pronounce '''swé'''. We have encountered these question words already in CH 2.10. There are ten of them but the first two have two forms. Here they are again ... | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''nén nós''' | |||

|align=center| what | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''mín mís''' | |||

|align=center| who | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''láu''' | |||

|align=center| "how much/many" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kái''' | |||

|align=center| "what kind of" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''dá''' | |||

|align=center| where | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kyú''' | |||

|align=center| when | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''sái''' | |||

|align=center| why | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''nái''' | |||

|align=center| which | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔai?''' | |||

|align=center| "solicits a yes/no response" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔala''' | |||

|align=center| which of two | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

The only time that you hear these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are in the same intonation contour as the verb "aika" in one of its forms. | |||

The only time that you see these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are sandwiched between two '''deumai'''. | |||

This is quite a bit different from English where question words have been appropriated to function as relativizers, complementizers and what have you (heads of free relative clauses). | |||

In the above ... when pronouncing words ... '''swé''' or '''aika''' is inserted where the first bracket appears. It could equally well be that '''swé''' or '''aika''' is inserted where the second bracket appears. It is deemed to not really matter that much. However in carefull writting the proper position of the quotative verb can be indicated. For example ... | |||

[[Image:TW_747.png]] | |||

In the above a pause (gap) is visible just above the top '''deupa'''. From that it is logical to deduce that '''swé''' or '''aika''' should be inserted after the "sods". (from the word order and intonation rules given earlier). But most of the time ... when reading out loud ... people do not take much heed to whether the quotative verb is placed over the '''deupa damau''' or the '''deupa dagoi'''. | |||

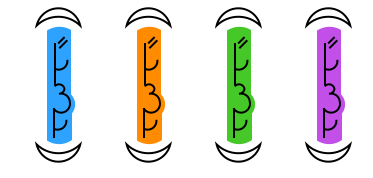

In a textblock, which you have a lot of dialogue it is common to colour code the "sods" with respect to the speaker. For example ... | |||

[[Image:TW_278.png]] Shown in better detail => [[Image:TW_750.png]] | |||

When this happens the '''deupa''' has no gold filling. It could be possible to drop the speakers name also once the colour coding scheme is established. This really depends upon how much dialogue is involved. Maybe each speaker would be mentioned again at the start of every textblock ... just to keep the protagonist <=> colour mapping alive in the readers mind. | |||

.. | |||

'''*''' In the very first sentence of this section I said that "quotative verb"is a verb which must be accompanied by a "sods" ... not quite true. The determiners '''dí''' and '''dè''' can take the place of a "sods". In these constructions '''dí''' refers to a "sods" that will be revealed imminently ... '''dè''' refers to a "sods" that was spoken in the past. | |||

If Jane pronounces an opinion about something ... if John had pronounced roughly similar in the past ... it would be fitting to say '''jono swori dè'''. | |||

If you are about to replay some utterance by John on a voice file, it would be appropriate to say '''jono swori dí''' just before playing the voice file. | |||

.. | |||

IMPORTANT ... The only time you hear direct speech is when '''swé''' or '''aika''' is present in one of its forms. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... '''jía''' expressing the conditional=== | === ... '''jía''' expressing the conditional=== | ||

Revision as of 16:14, 14 February 2019

... Two quotative verbs

..

béu has two quotative verbs ... swé and aika. What I mean by the term "quotative verb"is a verb which must* be accompanied by a string of direct speach ["sods" from now on]

swé = "say" and aika = ask .... ( that is to ask for information, to request something (to ask for) has a completely different root ... namely tama )

I guess it is intransitive because the speaker never takes the ergative ending "s". The spoken to (if mentioned) takes the dative ending "n".

[Some people would like to argue as to whether "sods" = an object or whether "sods" = a complement clause. I think this is not worth arguing about. It is similar to arguing about how many angels can stand on the end of a needle. ]

There is an ordering restrictions for a clause formed around a quotative verb ... the "sods" must appear adjacent to swé or aika. It doesn't matter which comes first but they must be adjacent ... normally both elements are pronounced in the same intonation contour. A second restriction is that there must be a pause at the other end of the "sods" ... the opposite end from the quotative verb. For example ...

John said "Ai ... go away" => jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo where aiʔdo is an interjection expressing frustration and ojo is quite a rough way to say "go away".

This can also be expressed as aiʔdo ... ojo swori jono or jono ... aiʔdo ... ojo swori or even swori aiʔdo ... ojo ... jono. The first two patterns are the most common followed by the third pattern and the fourth a distant last. Notice that the "sods" that I chose for demonstration purposes entails an internal pause.

If we introduced a dative element ...

John said to Jane "Ai ... go away" => jono jenen swori aiʔdo ... ojo

The above would be the most common ordering of constituents ... but again quite a bit of freedom with respect to word ordering.

The "sods" can be quite lengthy ... 2 or 3 or 4 clauses and follows as near as possible the speach pattern of the original speaker.

The béu orthography is a bit quirky when it comes to quotative verbs. In CH 1.8 we briefly mentioned the deupa. These are actually used to bracket any "sods". Also it is common to drop the actual quotative verb. (well after the time setting of the speach act(s) are revealed anyway). For example ...

The first one is graphically jono [ aiʔdo ... ojo ] ... (for an explanation of the graffic form of the interjection aiʔdo, look back to CH 1.2)

The second one is graphically jono [ bàu nái ]

These would be read as jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo and jono aikori bàu nái (John asked "which man")

But how do we know that swé should be associated with one and aika to the other ? Simple ... if you have a question word within the deupa then you know you should pronounce aika ... if not you pronounce swé. We have encountered these question words already in CH 2.10. There are ten of them but the first two have two forms. Here they are again ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| láu | "how much/many" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| dá | where |

| kyú | when |

| sái | why |

| nái | which |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

| ʔala | which of two |

..

The only time that you hear these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are in the same intonation contour as the verb "aika" in one of its forms.

The only time that you see these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are sandwiched between two deumai.

This is quite a bit different from English where question words have been appropriated to function as relativizers, complementizers and what have you (heads of free relative clauses).

In the above ... when pronouncing words ... swé or aika is inserted where the first bracket appears. It could equally well be that swé or aika is inserted where the second bracket appears. It is deemed to not really matter that much. However in carefull writting the proper position of the quotative verb can be indicated. For example ...

In the above a pause (gap) is visible just above the top deupa. From that it is logical to deduce that swé or aika should be inserted after the "sods". (from the word order and intonation rules given earlier). But most of the time ... when reading out loud ... people do not take much heed to whether the quotative verb is placed over the deupa damau or the deupa dagoi.

In a textblock, which you have a lot of dialogue it is common to colour code the "sods" with respect to the speaker. For example ...

When this happens the deupa has no gold filling. It could be possible to drop the speakers name also once the colour coding scheme is established. This really depends upon how much dialogue is involved. Maybe each speaker would be mentioned again at the start of every textblock ... just to keep the protagonist <=> colour mapping alive in the readers mind.

..

* In the very first sentence of this section I said that "quotative verb"is a verb which must be accompanied by a "sods" ... not quite true. The determiners dí and dè can take the place of a "sods". In these constructions dí refers to a "sods" that will be revealed imminently ... dè refers to a "sods" that was spoken in the past.

If Jane pronounces an opinion about something ... if John had pronounced roughly similar in the past ... it would be fitting to say jono swori dè.

If you are about to replay some utterance by John on a voice file, it would be appropriate to say jono swori dí just before playing the voice file.

..

IMPORTANT ... The only time you hear direct speech is when swé or aika is present in one of its forms.

..

... jía expressing the conditional

..

jía has three functions.

..

Also it has two shorthand forms ... the only word in the language to be so honoured. The leftmost word is never used. The => character used for the second function. The remaining character used for functions 1 and 3.

..

1) In most languages you can drop certain components if they are obvious from context. And when you do the remaining utterance stays unchanged. However béu does not work like that*. We saw in the previous section that the particles used to show cause/reason are different, depending upon whether they are followed by a simple noun or by a clause. The same happens when we are making a statement by way of comparison. For example ...

..

Thomas thinks as fast as John => tomo wòr saco làu jono

Now obviously "John thinks" is underlying here. However if you want to make "John thinks" overt you must change làu to jía ...

Thomas thinks as fast as John thinks => tomo wòr saco jía jono wòr

Notice that English patterns the same way for both the above examples.

..

2) In English we have the verb "to equal" ... it bit of a strange verb. Almost exclusively found in a mathematical setting. (The adjective "equal" has the same form as the verb "to equal" .. but anyway ... )

The béu particle jía is used in most situations where we find the English verb "to equal". In a setting such as 2+3=5 ... well there are no need for tense or aspect ... we are talking about a timeless truth. Also no need for person affixes ... the elements (arguments) involved are always stated the the left and the right of jía. Also no need for evidential markers ... the world of béu considers evidentials as appropriate for the human world ... but the world of mathematics is so far beyond the human world ... to have evidentials on a mathematical expression would be to drag the matheverse down into the dirt. Hence jía is an invarient particle. By the way jiagan = "equation".

..

3) The third function of jía is for considering contingencies. In English "if" is essential for considering contingencies. However "if" does not equate to jía. Let me explain ...

In English ... "if you go, they will kill you" ... two clauses ... the first introduced by "if" .... "if (A), (B)".

Sometimes "then" can introduce the second clause [ "if (A), then (B)"] but this is not considered essential in English. However some natlangs require a particle in front of the second clause. In Chinese the particle 就 jiù is needed.

béu requires gò in front of the first clause and jía in front of the second clause. For example ...

..

gò jiru jía gì dainuru => "if you go, they will kill you"

..

| gò | j-i-r-u | jía | gì | dain-u-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| that | go-2SG-IND-FUT | "equative particle" | you | kill-3PL-IND-FUT |

..

As well as Mandarin, French has a mechanism which is not a million miles away from the béu arrangement.

In classical and educated French, the complementizer "que" could function as a marker of protasis if the verb of the clause is in the subjunctive mood. The apodosis would be in the future tense, preceded by "et" (and) :

"Que je périsse, et elle périra" (périsse = subjunctive) = "if I perish, she will too"

"Si je péris, elle périra" (péris = indicative) = "if I perish, she will too"

..

* Now why have I set things up like this ... well in béu it is quite easy to define a clause. A clause is a chunk that contains one active verb (active verb = a verb having an "r" ). I guess I have set things up like this, so as to firmly draw a line between one clause constructions and two clause construction.

[ Note to self : why DO you want it like this ?]

..

... Here lies LIGA and TEKA

..

liga makes verbs which in themselves are quite compact more spread out. Possibly related to the verb ligai which means "to stay" or "to lie".

..

| koʕia | to cough | liga koʕia | "to be coughing", "to have a coughing fit" |

| timpa | to hit | liga timpa | "to be hitting" or "to assault" |

..

liga is never used with verbs that typically have an inherent long time duration. For example ...

*liga glarua beuba kewe would be translated as "I intend to be knowing the language of béu well" ... (not good in English either ... maybe OK in Indian English ?).

Simply glarua beuba kewe = "I intend to know the language of béu well" ... is more felicitous in both languages.

..

If translating from a language with a "perfective"/"imperfective" dichotomy, perhaps using liga for translation of the "imperfective" would work. However it should be dome sparingly. If every instance of "imperfective" was rendered with liga you would end up with a very very bad translation (the style would be judged attrocious by any béu speaker). Now in the very best register of béu this particle is used for a certain poetic effect, it is used sparingly and is not necessary for understanding what is being said. However people that are L1 speakers of a language having a perfective/imperfective tend to over-use liga. This is not really a problem, it just shows that they are not L1 béu speakers. Conversely people that are L1 speakers of language that lacks this distinction tend to not use liga enough. Again ... no real problem.

In certain situations liga can be translated as "keep". For example ...

liga doiku = keep walking

..

teka is the opposite of liga. It means "momentarily". Possibly related to the verb telka which means "to slip a little bit".

While in theory it can be used with almost any verb, it tends to be used disproportionately with a dozen or so verbs. For example ...

..

| bwí | to see | liga bwí | to watch over | teka bwí | to catch a glimpse |

| wòi | to think | liga wòi | to ponder | teka wòi | to think for a moment |

| ʕái | to want | liga ʕái | to yearn for | teka ʕái | to have an momentary urge |

..

So there is assymetry between the usages of liga and teka ... liga used with many verbs albiet verbs of short duration ... teka, while in theory can be used with many verbs, in practice the verbs usually used with it are quite restricted.

..

... Kyù and jé discarded

..

In the previous sections we have seen how to give time information. However there is another way to give the time ... with respect to an evert or action.

We will cover seven particles in this section which allow us to give time information with respect to an event ... jé kyù koca beda kogan began and jindu.

..

jé = kyù* = "while" or "when"

koca = before

beda = after

kogan = until

began = since

jindu = as soon as

In a similar manner to English, they can either introduce a clause, a noun (that designates a time) or an infinitive phrase (by the way ... I strongly object to the term "infinitive clause")

“After I ate breakfast”

“After the gold rush”

“After the eating of my breakfast”

The above are all time adverb phrases. A time adverb phrase is a dependent clause** (called an under clause in béu) ... shown in red below. The main clause is shown in yellow.

..

Tha arrow is the arrow of time*** ... with the past to the left (komo), and the future to the right (bene).

I have given events wavey borders to represent "not so well defined". So, for example, on the top diagram ... the main clause action could start before the under clause action ... it could also outlast the under clause action ... the important thing is that for a substantial amount of time, the two actions were going on at the same time.

In the bottom four examples I have made the under clause actions very short. This is for illustration purposes only. The under clause actions can actually have any length ... depend on the verb/situation.

Now these five examples show how two clauses can be joined in a timewise fashion. The béu rules are quite similar to English. That is ...

A) the under clause must be introduced with one of these 6 particles.

B) we can have main clause and then the under clause ... or the other way around.

Here are examples to illustrate the 5 examples above ...

..

1) kyù/jé = while, as, when, during ........ ( note to self : jé is definite : kyù not so ... = if ?? )

pás pintu saikaru kyù gís pazba saikiru = "I will paint the door, while you paint the table"

kyù gís pazba saikiru_pás pintu saikaru = "while you paint the table, I will paint the door"

kyù saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "while painting the table, you smoked"

..

2) koca = before

pazba saikaru koca pintu (saikaru) = "I will paint the table before (I will paint) the door"

koca pintu saikaru_pazba saikaru = "before I paint the door, I will paint the table"

koca saiko pintu_pás pazba saikaru = "before painting the door, I will paint the table"

..

3) beda = after

pintu saikaru beda pazba (saikaru) = "I will paint the door after (I will paint) the table"

beda pazba saikaru_pintu saikaru = "before I paint the door, I will paint the table"

beda saiko pazba_pás pintu saikaru = "after painting the table, I will paint the door"

..

If you wanted to emphasize that the first action will continue until the second action you would use ...

4) kogan = until

gís huʒiri kogan dare saiko pazba = "you smoked until I started to paint the table"

kogan dare saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "until I started to paint the table, you smoked"

kogan día saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "until starting to paint the table, you smoked"

..

If you wanted to emphasize that the first action has been continuing all the time since the second action you would use ...

5) began = since

gís ʔès huʒira figo care saiko pazba = "you have smoked since I stopped painting the table"

| gí-s | ʔès | huʒ-i-r-a | began | c-a-r-e | saiko | pazba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| you-ERG | already | smoke-2S-IND-PRES | since | stop-1S-IND-PAST | painting | table |

==> "you have smoked since I stopped painting the table"

began care saiko pazba_gís huʒira = "since I stopped painting the table you have smoked"

began cùa saiko pazba_gís ʔès huʒira = "since stopping painting the table, you have smoked" ... [By the way ... began ìa saiko pazba_gís ʔès huʒira = "since finishing painting the table, you have smoked" ]

..

There is one added complication in the above scheme ... if the intersect time of the two actions is in the future, then jindu (<jín "a moment" + dù "exact") can be used instead of began.

..

..

* In most situations jé and kyù can be used interchangeably. However only kyù can take the adverbial marker (kyùas = meanwhile) and only jé can be used to introduce the time of day number.

** I guess I should say what is the difference between a main clause and an under clause. (I should read about what other linguists say about this some day). Take the sentences ...

(1) I will finish this drink before I go home. ......... (2) I will go home after I finish this drink.

In terms of pure logic these both mean exactly the same. Also the choice of whether a verb is in the main or the under clause says nothing about the speakers attidude towards that verb ... i.e. relish, disgust, foreboding, sadness etc. But is seems that the verb in the main clause is the target of the speakers determination/willpower/resolve whereas the verb in the underclause is the target of nothing. I guess you can say it is background material..

*** The organization of the Chinese writting system seems to have affected the language itself. The primary writing direction was top_to_bottom so of course the calendar was written top_to_bottom as well. From that "above" got associated with "the past" and "below got associated with "the future".

午 wǔ "noon" : 上 shàng "above" : 下 xià "under" => 上午 shàngwǔ "morning" : 下午 xiàwǔ "afternoon"

A similar thing happened in béu. The practitioners of béu are above all engineers and the algebraic convention of having time along the horizontal axis has affected the language somewhat.

..

... Word building

..

Many words in béu are constructed from amalgamating two basic words. The constructed word is non-basic semantically ... maybe one of the concepts needed for a particular field of study.

..

In béu when 2 nouns are come together the second noun acts as an attribute of the first*. For example ...

toili nandau (literally "book word" ... "book" is the head and "word" is the attribute).

Now the person who first thought of the idea of compiling a list of words along with their meaning would have called this thing he created toili nandau.

However over the years as the concept toili nandau became more and more common, toili nandau would have morphed into nandəli.

Often when this process happens the resulting construction has a narrower meaning than the original two word phrase.

..

There are 4 steps in this word building process ...

1) Swap positions : toili nandau => *nandau toili

2) Delete syllable : *nandau toili => *nandau li

3) Vowel becomes schwa : *nandau li => *nandə li

4) Merge the components : *nandə li => nandəli

In the above, the only valid constructions are toili nandau and nandəli. The other constructions are only shown for demonstration purposes. From now on I will leave out the * (indicating non-validity) Below are a number of examples. They are divided up into sets, depending on how many syllables in the head and how many in the attribute.

..

... head 2 : attribute 2

..

[Note to self : are you totally happy with this example ?]

laŋku = shadow, reflection

miaka = echo, response, effect

Which produce miakəka meaning "subtle influence" or "to subtly influence"

..

And the case when the attribute ends in a consonant ...

megau plus peugan : "body of knowledge" + "society"

1) Swap positions : peugan megau

2) Delete syllable : peugan gau

3) Delete the coda and neutralize the vowel : peugan gau => peugə gau

4) Merge the components :peugə gau => peugəgau

..

And the case when the main word has a double consonant before the end vowel ...

kanfai plus gozo : "merchant" + "fruit"

1) Swap positions : gozo kanfai

2) Delete syllable : gozo fai ............................. Note kan is deleted, not just ka

3) Vowel before the final consonant becomes schwa :gozo fai => gozə fai

4) Merge the components : gozə fai => gozəfai

..

... head 2 : attribute 1

..

nandau plus sài : "word" + "colour"

1) Swap positions : sài nandau

2) Delete syllable : sài dau

3) ---

4) Merge the components : sài dau => saidau

Note that in this case the semantic difference between nandau sài and saidau is quite large ... we have aboiut 10 of the first but around 1,000 of the second.

..

ifan plus kwò : "duo" + "wheel"

( kwò "wheel" is related to kwè "to turn")

1) Swap positions : kwò ifan

2) Delete syllable : kwò fan

3) ---

4) Merge the components : kwò fan => kwofan

..

... head 1 : attribute 2

..

And when the head is a monosyllable ...

wé plus deuta : "manner" + "soldier"

1) Swap positions : wé deuta => deuta wé

2) ---

3) Vowel becomes schwa : deuta wé => deutɘ wé

4) Merge the components : deutə wé => deutəwe

..

... head 1 : attribute 1

..

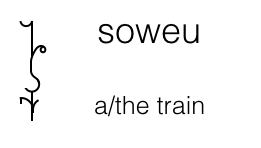

wèu plus sò : "vehicle" + "row"/"series"

1) Swap positions : wèu sò => sò wèu

2) ---

3) ---

4) Merge the components : sò wèu => soweu

..

sword.spear => weaponry ... shield.helmet => armour, protection ... knife.fork => cuttlery ... table.chair => furniture

There are no cases where both contributing words are monosyllables.

As with the schwa-form and the i-form verbs ... the schwa is represented by cross.

When spelling words out, this cross is pronounced as kano ... meaning "link", "connector", "connection", "association" or "relationship".

Notice that when you hear nandəli, deutəwe or peugəgau you know that they are a non-basic words (because of the schwa).

This method of word building is only used for nouns.

..

* Actually there are three words that can be used to bind the two words together ... perhaps if you want to make the relationship between the two more concrete. These words are yó "property, gù "master"/"lord" and kài "kind"/"type"

waudo yó bàu = "the man's dog", bàu gù waudo = "the man who owns a/the dog", loweu kài hauheu = "a/the school bus"

But as I said before, usually speakers are happy to drop these linking words.

By the way "whose" can be translated into béu using the gù construction ... "the man whose dog bit me" => bàu gù waudo nài pà ilkori ... in theory this construction is ambiguous ...

1) the man (who owns a dog) bit me

2) the man whose dog bit me

Actually easy to tell apart as 1) is a complete clause and 2) is only a part of a clause. Also if 1) was meant a pause would be introduced. That is 1) = bàu gù waudo_nài pà ilkore

..

... The particles làu, kài, "wé nài" and ?à ... this is quite complicated

..

There are 4 main uses for làu

..

1] The first use is when we are using the extended number set. làu stands between the noun (senko) and the extended number ...

..

3,05112 elephants => sadu làu uba wú odaija

| sadu | làu | uba | wú | odaija |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| elephant | "partitive particle" | 3 | 123 | 51 |

..

Note ... the singular form of senko always used when quantity is given by this method.

We have already touched on this in the previous chapter [ see the section Numbers ... (the extended set) ].

I call làu a partitive particle when it is doing this function.

To the left of làu, the noun always has a generic meaning hence in this position it would never take the kai prefix. [ cf. sadu = elephant : kaizadu = elephant-kind, "the elephant" (as a species) ... see the next chapter ]

So *kaisadu làu uba wú odaija is illegal.

This construction is often seen with "magnifier" duplication ...

sadu làu wú wú = thousands of elephants : sadu làu nàin nàin = millions of elephants : sadu làu hungu hungu = billions of elephants

When specifying an amount of an olus, làu is use with any number, not just with an extended number ...

..

Two cups of hot milk => ʔazwo pona làu hói hoŋko

| ?azwo | pona | làu | hói | hoŋko |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| milk | hot | "partitive particle" | 3 | cup |

..

2] I also call làu a partitive particle when it is doing its second function ...

..

Three of these doctors => moltai.a dí làu léu

| moltai.a | dí | làu | léu |

|---|---|---|---|

| doctors | this | "partitive particle" | 3 |

..

Note ... the plural form of senko is always used for this construction.

..

Two cups of this hot milk => ʔazwo pona dí làu hói hoŋko

| ?azwo | pona | dí | làu | hói | hoŋko |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| milk | hot | this | "partitive particle" | 3 | cup |

..

Of course, for an olus there is no plural form.

This second construction is used when we are taking a portion of a larger amount. The first construction is used when we are taking a portion of X out of the sum total of all the X in the universe.

For the olus, there is not so much difference between function 1) and function 2).

..

3] I also call làu a qualitative particle when it is doing its third function. Here làu is equivalent to English "as" in some of "as"'s functions ...

..

Question ... tomo r jutu láu => "how big is Thomas ?"

Answer[A] .... tomo r jutu làu jono => "Thomas is as big as John"

Answer[B] .... tomo r wì jutu jonowo => "Thomas is less big than John"

Answer[C] .... tomo r yú jutu jonowo => "Thomas is bigger than John"

Answer[D] .... tomo bù r jutu làu jono => "Thomas is not as big as John"

Notice that D, invariably in English, makes Thomas smaller than John. Not so in béu. A B and C tend to be used a lot more than D.

Note ... in English, in the negative, "so" can be used instead of "as" .... "not as good as" = "not so good as"

[Note to self : get rid of -ge ? .... use it only in NP ? an alternative to C ? ]

This usage is not just for copula+adjective constructions, it can also be used for verb+adverb constructions ...

Thomas thinks as fast as John => tomo wòr sacois làu jono

Also ... Thomas thinks faster than John => tomo wòr yú sacois jonowo etc.

..

4] In most languages you can drop certain components if they are obvious from the context. And when you do this there is no other differences to the sentence (as far as I know). Not so in béu. Sometimes làu must become jía when a verb/copula is overt. Take the example tomo wòr sacois làu jono "Thomas thinks as fast as John" ... obviously "John thinks" is underlying here. However if you want to make "John thinks" overt you must change làu to jía ...

Thomas thinks as fast as John thinks => tomo wòr sacois jía jono wòr

Now why have I set things up like this ... well in béu it is quite easy to define a clause. A clause is a chunk that contains one active verb (one verb containing a verb). It is to firmly draw a line between one clause constructions and two clause constructions that I insist on làu => jía

Here is an other example of jía in action ...

tomo r jini jía bù byór jò banhain = Thomas is so clever that he doesn't have to go to school

Here is the above in different words (a bit of revision) ... tomo r jini jía bù r neʒi gò jòr banhain ... but in béu the shorter version is always preferred.

And another example of the làu/jía split ...

Thomas walks as much as John (walks) => tomo doikor làu jono or tomo doikor jía jono doikar

And I think I should mention the construction ... tomo doikar hè jía jono doikar. This means the same as above plus the information that they both walk a lot.

..

..

1] I also call kài a qualitative particle when it is doing its first function ...

..

| jono | r | kài | dada | ò |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like | older brother} | his |

=> John is like his older brother

| jono | r | kài | dada |

|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like/as | older brother} |

=> John is like my older brother

[Note to self : get rid of the above example]

..

2] Sometimes kài can best be translated as "made of" ...

a/the wooden house => nambo kài wuda

the house is made of wood => nambo r kài wuda

..

3] Sometimes kài can best be translated as "for" ...

water for drinking => moze kài solbe

water for washing clothes => moze kài laudo

this water is for washing clothing => moze dí r kài laudo

(in the above three examples, kài and what follows it can be considerd an adjective)

..

4) In the fourth function kài actually merges with a following senko ...

elephant = sadu

elephant-kind = kaizadu

this is actually a noun, the idea being something like "that which is like an elephant"

[ Note ... it is interesting that the béu word for "species" is kaija. Probably from " kài aja ", aja being an obsolete word for "one". ]

..

5) In its fifth function kài actually merges with a following saidau ...

red = hìa

reddish = kaihia

..

6) And the sixth function ...

| gì | r | gombuʒi | kài | jono |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | are | argumentative | like | John |

=> you are argumentative like John .............................. i.e. in the same manner ... for example ... shouting over other people when they try and put forward their arguments

..

This only is applicable to "complicated "adjectives ... adjectives that like have internal structure. I find it difficult to imagine a situation where this construction would be suitable for an adjective like "short".

I see short as one dimensional while I see gombuʒi as multifaceted.

You are treating gombuʒi ss one dimensional when you say ...

..

| gì | r | làu | gombuʒi | kài | jono |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | are | as | argumentative | like | John |

=> you are as argumentative like John ................ (function 4 for làu and function 1 for kài)

..

So there we have it ... 4 functions for làu and 7 for kài. It is fitting to introduce wé nài at this point because wé nài's usuage overlaps with kài.

..

| gì | r | gombuʒi | wé | nài | jono |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | are | argumentative | manner | that | John |

..

This means exactly the same as the last example for kài

The above can be considered a contraction of gì r gombuʒi wé nài jono r or gì r gombuʒi wé nài jono r gombuʒi

We can see that now we have two clauses. In béu, one active verb means one clause ... very simple. So in the béu linguistic tradition ...

gì r gombuʒi wé nài jono r = 2 clauses : gì r gombuʒi wé nài jono = 1 clause ...... even though both these examples mean the same.

..

Now the wé nài construction has no subtle way to indicate whether we are thinking of gombuʒi as a one dimensional concept or as a multifaceted concept.

Hence gì r gombuʒi wé nài jono also means "you are argumentative to the same degree as John"

You must use your knowledge of the situation to disambiguate. For example in ...

..

| jono-s | huz-o-r | wé | nài | kulno |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | smoke-3SG-IND | as | chimney |

=> John smokes as a chimney

..

It is obvious that John's smoking can in no way resemble a chimney, and we must be talking about "degree" here.

| jono-s | huz-o-r | sù | kulno |

|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | smoke-3SG-IND | like | chimney |

=> John smokes like a chimney

sù = like, as much as

..

XXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXX

..

Note ... all the above should be actually two clauses but because of truncation ... [ a chimney ] <= [ a chimney smokes ] ... [ before ] <= [ she used deceit before ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is argumentative ] ... [ agreed ] <= [ all parties agreed ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is ] ... these constructions often appear as if only a NP follows kài.

Usually for particles that can either be followed by a NP or a clause, I add gò after the particle when a clause follows. This is to prevent errors in comprehention. For example jì means "for" and is followed by a NP (usually a person). I have jì gò meaning "in order that" ... jì gò being followed by a clause. In béu the first word of a clause is often a noun. If I had jì meaning "in order that" there might be misunderstanding (albeit temporary). English does this also in many constructions [ I should go into this more fully ??? ]. Of course I could have a totally different particle for "in order that" but I wanted to emphasis the semantic overlap between these to constructions.

But there is no chance of misunderstanding when kài is heard ... it is always followed by a clause. Even in (5) what we have is a clause. The clause is jono r (with the r dropped). Actually kài means "in the manner or roll specified" ... the last bit added to include cases like (5).

..

Note ... kài can not be followed by an adjective.

There are 5 nouns that are associated with 5 of these above question word / indefinite pairs. làus = amount, quantity : kàin = kind, sort, type : dàs = place : kyùs accasion, time : sàin = reason, cause, origin

These 5 nouns are never followed by nài. The table below is interesting. It shows the logical equivalence of a hypothetical expession (on the LHS) and the logical equivalent actually used (on the RHS).

..

*làus nài => làu

*kàin nài => kài

*dàs nài => dà

*kyùs nài => kyù

*sàin nài => sài

..

There are two adjectives associated with these question word / particle pairs. laubo meaning "enough" and kaibo meaning "suitable".

Also there are two nouns associated with these question word / particle pairs. lauja meaning "level" and kaija meaning "species/model".

sài = because of

dari solbe sài ò = I started to drink because of her .................................................. sài ò can be considered an adverb of reason.

Note ... sài means "because of" ... sài gò means "because"

To say something like "john is as good at writing as jane" you have to use ʔà (or ʔàbis) ... see the next section.

..

Note that 3) and 8) do not mean the same thing ... kài defines a multi-characteristic concept (thing or action) while làu specifies position* on a uni-characteristic scale. [* or "degree" or "amount"]. So làu introduces only a quantity and kài intruduces a quality or manner.

..

..

I find the above table interesting. It is skewed ... OK pí wé nài ("in the manner that") can be used but it hardly ever is. Usually kài = "in the manner that". Why is it skewed ? My answer is ...

"For everyone the most important things around them are other people. And the most important "attribute" of a person is "how" they behave."

Hence kài has supplanted pí wé nài.

Also notice that any adjective outwith a NP has to be introduced by the copula, hence sàu kài instead of simply kài.

..

Note ... nù r làu jutu saduwo and nù r jutu kài sadu do not mean the same thing ... nù r làu jutu saduwo would be said when you have one specific sadu "elephant" in mind.

So nù r làu jutu saduwo => "they're as big as the elephant" ... nù r jutu kài sadu would be said when you are talking about elephants in general. So => "they're as big as elephants"

..

| jono-s | klud-o-r | wé | nài | tomo-s | klud-o-r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG | writes-3SG-IND |

=> John writes like Thomas writes ........................................................ in the following examples kài and what follows can be considerd an adverb of manner.

| jono-s | klud-o-r | wé | nài | tomo-s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG |

=> John writes like Thomas ...........................................Note ... the final verb has been dropped but Thomas keeps the ergative marking.

| taud-o-r-a | wé | nài | hunwu | tú | húa | gayana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to be annoyed-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | bear | with | head | aching |

=> he/she is annoyed like a bear with a headache

(Note to self .... is gayana still valid)

| bù | ?oim-o-r-a | wé | nài | fiʒi | mù | moze |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| not | to be happy-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | fish | out | water |

=> he/she is unhappy like a fish out of water

Note ... the wide variety of things being compared ... clause to clause : clause to noun : noun to noun

..

Good, Better, Best

..

làu is part of a larger paradigm ... the comparative paradigm ... demonstrating with the help of bòi ("good") ...

..

| >>> | boimo | best |

| > | boige | better |

| = | làu bòi | as good |

| < | boizo | less good |

| <<< | boizmo | least good |

..

The top and the bottom items are the superlative degree and so have no "standard of comparison".

The fourth one down is used less frequently than the second one down. This is because its sentiment is sometimes expressed by negating the third one down. For example ...

gì bù r làu bòi pawo = "you're not as good as me" can be used instead of gì r boizo pawo "you are less good than me"

[ actually gì r boizo pawo would be the normal way to express this sentiment. But gì bù r làu bòi pawo would be used, for example, as a retort to "I'm as good as you" ]

The superlative forms are found as nouns more often than as adjectives. That is boimo and boizmo are rarer than boimos and boizmos. (see table below)

..

boimos = the best : bàu boimo = the best man

boizmos = the least good : bàu boizmo = the least good man

..

[ you are argumentative like John but you are even worse ] ... explain this more

... ?ài

..

The same or not the same

..

ʔài = "same"

bù ʔài = "different"

Note ... for "the other", NP before the verb : for "another", NP after the verb)

1a) jono lé jene sùr ʔài bèn = "John and Jane are the same" ... logically the bèn is unnecessary, but it is often included ... euphony.

1b) jono r ʔài jenewo = "John is the same as Jane"

The above two examples are ambiguous as to whether John and Jane are the same w.r.t. one characteristic or the same w.r.t. all characteristic.

2a) jono lé jene r ʔài jutuwo = "John and Jane are the same size"

2b) *jono r ʔài jenewo jutuwo = "John is the same as Jane, sizewise" = "John is the same size as Jane"

The above is not allowed ... there is a rule saying that you can't have two consecutive -wo endings. So 2b) has to be re-assembled as ...

jono r làu jutu jenewo .... see Ch2.11.1

[Note jutuwo is derived from jutumiwo but the mi "ness" is invariably dropped.

ʔàibis = similar

ʔài dù = exactly the same

ʔaimai = similarity

lomai = difference

To say something like "John is as good at writing as Jane" we can not say *jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo [ ??? ] [ two consecutive -wo no good ? ]

You must use a sort of topic comment construction.

wo kludau bòi_jene r ʔài jonowo or wo kludau bòi_jene lé jono r ʔài

... The 7 types versus basic types

..

I have heard of people constucting languages and their main aim from the start was to create a language that contained only nouns or only verbs or what have you. I have always considered this a bit silly ... however it appears that I have arrived at such a position myself ... well at least as to the non-derived (basic form) of the words*.

..

..

The base form of béu verbs are the manga which you can consider an "infinitive" or a "verbal noun". "MaSdar" if you will. To get a finite verb [called a "hook word" in béu] it must go through a derivational process [see Ch 3.1 for more information].

The béu adjectives seem to straddle two categoties ... nouns and adjectives. For example gèu means both "green" and "greenness" ("the green one" is represented by the saidaus gèus). But this is similar to many languages. For example in the English phrase "green is good", "green" must be a noun.

In béu (as in English) gèu will most often occur as an adjective. In béu when gèu must appear as a noun in a position where it might be mistaken for an adjective it is put into a NP with head kuwai ... kuwai = property, quality, attribute, characteristic, feature. So kuwai gèu is a NP meaning "greenness". In English when "green" must appear as a noun in a position where it might be mistaken for an adjective, it is changed into a noun with the affiX "ness" of course.

By the way ... there is one sure way to check if a word is saidau or not. If a word can take the intensifier sowe then the word is saidau (or a saidaun but you know it is saidau if it doesn't end in n)

(Note to self ... what béu word class is kuwai )

As a theoretical basis I am following Basic Theory as forwarded by RMW Dixon in his trilogy of the same name. I don't consider béu to diverge from Basic Theory. Just some of my categories are sub-categories of Basic Theory categories.

*In the chart we are ignoring grammatical words ... the fengi.

..

..... The 7 types of word

..

All words belong to one of the following 7 categories ...

..

1) fengi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the other categories. Interjections, numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners and certain words that would be classed as adverbs in English, are all classed as fengi.

An example is Í .. the preposition indicating the dative.

..

..

2) senko = object

An example is bàu ... "a man"

..

3) olus = material, stuff

An example is moze ... "water"

..

4) saidau = adjective

An example is nelau ... "dark blue"

..

5) manga = a noun ... closest to the infinitive in English ... also I call it "verb base" as finite verbs are built up from this form.

An example is twá ... "to meet" (the concept of "meet" disassociated from any arguments, tense, aspect or whatever).

..

6) mangan = a noun. A mangan represents one instance of the activity denoted by the manga. For example ...

twán ... "a\the meeting"

..

7) saidaun = a noun derived from an adjective. The saidaus means an object possessing the property denoted by the saidau.

An example is nelaun = a/the dark blue one : nò nelaun = a/the dark blue ones

..

..

The mangan and saidaun are transparently derived from manga and saidau so there is no need to list them separately in a dictionary.

..

..... Correlatives

I GOT RID OF THE CORRELATIVE SPECIAL SYMBOLS ... TO CLEVER BY HALF

..

| uda | everywhere | uku | always | ubu | everybody | ufan | everything |

| juda | nowhere | juku | never | jubu | nobody | jufan | nothing |

| ida | anywhere | iku | anytime | ibu | anybody | ifan | anything |

| eda | somewhere | eku | sometime | ebu | somebody | efan | something |

The above 16 correlatives all have a special symbols (ignore the blue and red squares).

If you wants to make plural any word from the last two rows, you must revert to the nearest generic noun available and build up a NP in the normal way..

| ida | anywhere | iku | anytime | ibu | anybody | ifan | anything |

| nò dà ín | any places | nò kyù ín | any times | abua ín | any people | fanyoi ín | any things |

| eda | somewhere | eku | sometime | ebu | somebody | efan | something |

| nò dà èn | some places | nò kyù èn | some times | abua èn | some people | fanyoi èn | some things |

A further 3 of these special symbols are shown below ....

..

..

The short-hand forms are always used.

..

(Note to self : resolve the stuff below)

The columns are related to the words ... dàn = place ... kyùs = time/occasion ... glabu = person ... fanyo = thing

ubu can mean "each person" and "all the people". If they act together uwe can be added. If they act individually bajawe can be added.

..

..... Some anaphora rubbish

WELL I MIGHT GET A PARTICLE OR TWO FROM THE BELOW ... SO ???

..

ò is used to represent an person, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

ʃì is used to represent an object, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

só is used to represent an scenario, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

The above would be used in such sentences as ... "She acquiesced to return to Crosby's hotel room ... which was a very bad idea".

..

Four (five with nai.as ?) other particles also take -as. They are ...

| lau.as | to that degree, as much as .... will not |

| kai.as | thus, so, in that way |

| sai.as | for that reason |

English uses that for anaphora in the above examples.

All these words are overwhelmingly/always ? utterance final.

..

..

..... Old morning/afternoon

..

falaja = afternoon : falajas = in the afternoon/every afternoon .... (jé) falaja = in the afternoon ......

yildos = morning : yildozas = in the morning/every morning ....... (jé) falaja = in the afternoon .......

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences