Béu : Discarded Stuff: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== ... possible ... possibly== | |||

This one can be a bit confusing for English speakers. "possible" = "doable" : "to be doable" is an intransitive verb corresponding to the transitive verb "to be able to". However "possibly" is not to "possible" as "quickly" is to "quick". In fact "possibly" = "maybe" which means "middle likelihood". The mechanism for this is ... well there might not be any impediment to an action happening. But that action is only going to actually happen some of the times. You could say "middle likelihood" codes the likelihood of an action happening from around 5 % up to 95 % (the exact percentage varies depending on the exact situation). Above 95 % the indicative verb form is used by itself. Below 5 % the negated indicative verb form is used. It is not inevitable that "possibility" => "middle likelihood". In English, the word "perhaps" indicates "middle likelihood" yet has no history as a marker of "possibility". | |||

.. | |||

== ... kyù etc etc== | == ... kyù etc etc== | ||

Revision as of 22:14, 31 October 2016

... possible ... possibly

This one can be a bit confusing for English speakers. "possible" = "doable" : "to be doable" is an intransitive verb corresponding to the transitive verb "to be able to". However "possibly" is not to "possible" as "quickly" is to "quick". In fact "possibly" = "maybe" which means "middle likelihood". The mechanism for this is ... well there might not be any impediment to an action happening. But that action is only going to actually happen some of the times. You could say "middle likelihood" codes the likelihood of an action happening from around 5 % up to 95 % (the exact percentage varies depending on the exact situation). Above 95 % the indicative verb form is used by itself. Below 5 % the negated indicative verb form is used. It is not inevitable that "possibility" => "middle likelihood". In English, the word "perhaps" indicates "middle likelihood" yet has no history as a marker of "possibility".

..

... kyù etc etc

..

11) kyù = when

kyù twaru jene plùa òn fyaru = When I see Jane I will tell her.

The English conditional particle "if"* is also translated as kyù

kyù twaru jene plùa òn fyaru = If I see Jane I will tell her.

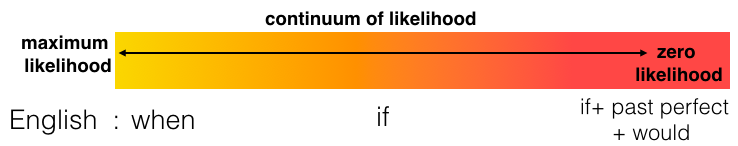

Actually we have a continuum here ... the likelihood of the first verb occuring can range from pretty definite (well as definite as a future event can be) to total zilch. The names "hypothetical" are given to the mid region of this continuum and "counterfactual" to the zilch end.

In English the conjuntion "when" is used on the left, but towards the middle "if" takes over and goes to the extreme right. Also the condition clause takes past perfect markings and "would" is used in the consequence clause.

..

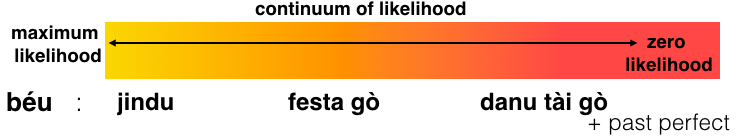

In béu kyù can be used across the entire continuum. However it can be replaced by jindu or festa gò or danu tài gò if thought appropriate. jindu means "as soon as", festa means "case, situation, scenario" and danu tài means "suppose, imagine, assume" (if you analyze danu tài it is the imperative form of "to place in front"). béu also uses the "past perfect" tense in counterfactual situations.

..

*Other languages to conflate "when" and "if" is German (with "wenn") and Dutch (with "als"). It is possible to disambiguate in German, by using "sobald" or "falls" instead of "wenn".

* In English, there is another function for "if" ... it introduces a complement clause when the main clause verb is an "asking" verb. "whether" can also fulfill this function. The particle in béu that fulfills this function is wai.a. wai.a has only this function.

Now let's give the example sentence a habitual meaning ... say Jane fervantly supports Manchester United and the speaker always hears the latest results before Jane. So we have ...

kyù twár jene ʃì òn fyar = When I see Jane I will tell her.

toili gìn naru kyù twairu = "I will give you the book when we meet"

jonos jenen toili nore kyù twure = "John gave Jane the book when they met"

Only in speculative circumstances can kyù be fronted ... then it means "if" .... usually the future tense in both clauses.

kyù twairu gò toili gìn naru = "If we meet I will give you the book" .... note gò separates the clauses.

kyù twairiyə gù toili gìn naru = "If we had met ????

..

... The advisory

..

Also called the S-form.

..

There is a form similar to the R-form. However it only has two slots. The personal pronoun slot and A slot that has "s". Basically it is used for giving advice. The speaker is not upset if the hearer doesn't act (as he would be if it was a command) and he is not upset if he doesn't get feedback/advice/approval/disapproval (as he would be if it was a hortative). He is simply giving the listener some advice and the listener can chew it over at his leisure ... or he can completely disregard what is said ... up to him/her. The advice could be for the common good or the good of the listener (not realy for the good of the speaker ... unless the speaker and the listener identify together ... in which case we are talking about the common good). Maybe this form is equivalent to "should" in English.

..

solbis moze = You should drink some water

solbas moze = I should drink some water

solbos moze = He should drink some water

For mono-syllables an be- is prefixed as well ...

jò = to go

bejis nambon = You should go home

bejas nambon = I should go home

bejos mambon = She should go home.

..

I simply call this the S-form instead of making up a silly name.

..

The R-form when used with náu "to give" results in two forms ... benis and benes that when followed by tà play an important role in the grammar of béu

benis means "you allow" or "let" [benes being the form used when talking to more than one person]

benis tà nambon jàr = Let me go home

benis tà nambon jùar = Let us go home (not including you)

benis tà nambon jòr = Let him go home

benis tà nambon jùr = Let them go home

It is usually only used with one of the 4 third parties listed above.

In linguistic jargon the benis tà form would be called the "cohortative". So we have ...

..

..... Old Questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

[ Note ... there was also a "whom" until quite recently ]

These are the most profound words in the English language. (When I say "profound" I am talking about "time depth" ... these words are very very old)

However these question words have over the mellenia been sequestered to support other functions. For example "who" can be used to ....

1) Solicit a response in the form of a persons identity

2) As a relativizer particle ... for example ... "The man who kicked the dog"

3) As a complement clause particle ... for example ... "She asked who had kicked the dog"

4) In the compound "whoever" which is an indefinite pronoun.

Only in the first example is "who" asking a question.

..

béu is quite rich when it comes to question words. It has eleven ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| láu | "how much/many" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| dá | where |

| nái | which |

| kyú | when |

| sái | "why"* |

| gó | "why"* |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

| ʔala | which of two |

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. These words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

Notice that there is no one word for "how" in the above table. This is expressed by the 2-word expression wé nái "which method".

On the other hand, béu has single words where English requires the 2-word expression "how much" and the 3-word expression "what kind of"

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words). The dative forms are í nén and í mín.

..

English is among the 1/3 of world languages which fronts a question word. béu fronts 5 of its 11 question words ... nén mín sái gó and kyú.

Now láu kái dá and nái are stuck within** their NP (refer back to the diagram in the section titled seŋko) and the elements in a NP are fixed. Well it is possible that láu could come sentence initial but not kái dá and nái as they are positioned to the right of the mandatory head.

As for the other 2 question words ... ʔai? always come sentence final ... and ʔala comes between two elements of the same class (these elements subject to the usual ordering rules)

Here are some examples of these words in action ...

..

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... í mín bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... á bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái bàus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha bàus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

Question 8 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 9 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

..

Occasionally you hear nenji instead of sái. This is just nén + the tenth pilana ... so it means "for what".

"how" is expressed as wé nái which means "which way" or "which manner"

* Let me explain why we have two "why"s. First I will digress a little. Nearly all the languages of the world have a question word directly equivalent to the English word "who". However languages having a plural of "who" are very very rare. The reason is not difficult to figure out. When you ask "who", you are asking about something that is unknown to you ... the plurality of that "something" is also unknown. (Not only would a singular-plural distinction for "who" be unnecessary ... it would be asocially awkward ... If in asking a question you picked the wrong plurality (i.e. "who".singular when the answer is plural or "who".plural when the answer is singular) the person answering would have to set you right ... would have to contradict you. OK ... in a similar way the word "why" could be split in two ... into "why".future and "why".past. "why".past would ask about a state or action that existed/happened previously and lead to a current state or action. "why".future would ask about a state or action desired in the future and the current state or action exists in order to bring about. Well the two "why"s are rare for exactly the same reason that the two "who"s are rare. But actually in some cases you DO know that it is a future state or action. sái is the normal word for "why", but in about 10 % of times you come across a gó "why".

** These 4 words often stand alone. But when they do, they are still considered within a NP ... only that the rest of the NP has been dropped.

| 1) | làu | as, so | làus | amount | ||

| 2) | kài | like, as | kàin | kind, sort, type | ||

| 3) | dà | where | dàs | place | ||

| 4) | kyù | when | kyùs | occasion, time | ||

| 5) | sài gò | because | sàin | reason, cause, origin | sài | because of |

| 6) | jì gò | in order to | jìan | goal, aim, intention | jì | for |

..

The RHS of the above table has six generic nouns. Not so much to say about them, but the related particles (shown on the LHS) are more interesting. The way these function is shown below ...

..

nài by itself is used to qualify a situation rather than a noun.

For example "John hit a woman, which is bad" would be rendered jonos timpori glá_nài r kéu

Note that there is a pause between jene and nài. If there was not this gap, the sentence would mean "John hit the woman who is bad"

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences